Last updated: May 30, 2024

Article

Equal Education Activism at the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial

Photo by Arlan Fonseca

This article is part of the series "Desegregation in the Cradle of Liberty." This series explores the Black struggle for equal education in Boston from 1787 to 1976, culminating with protests and violence experienced under forced busing in Boston in the 1970s.

During the 20th century education movement in Boston, activists rallied and protested throughout the city, including at many historic sites that now comprise the National Parks of Boston. Prominently placed on Boston Common across from the Massachusetts State House, the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Massachusetts Regiment Memorial offered a highly visible and easily accessible location for many of these gatherings. Furthermore, the legacy of the struggle for freedom embodied in the Memorial, which honors one of the first and most influential Black regiments of the US Civil War, provided a powerful thematic backdrop for many of the education activists who gathered there.

Some of these signature moments at the Memorial are captured below.

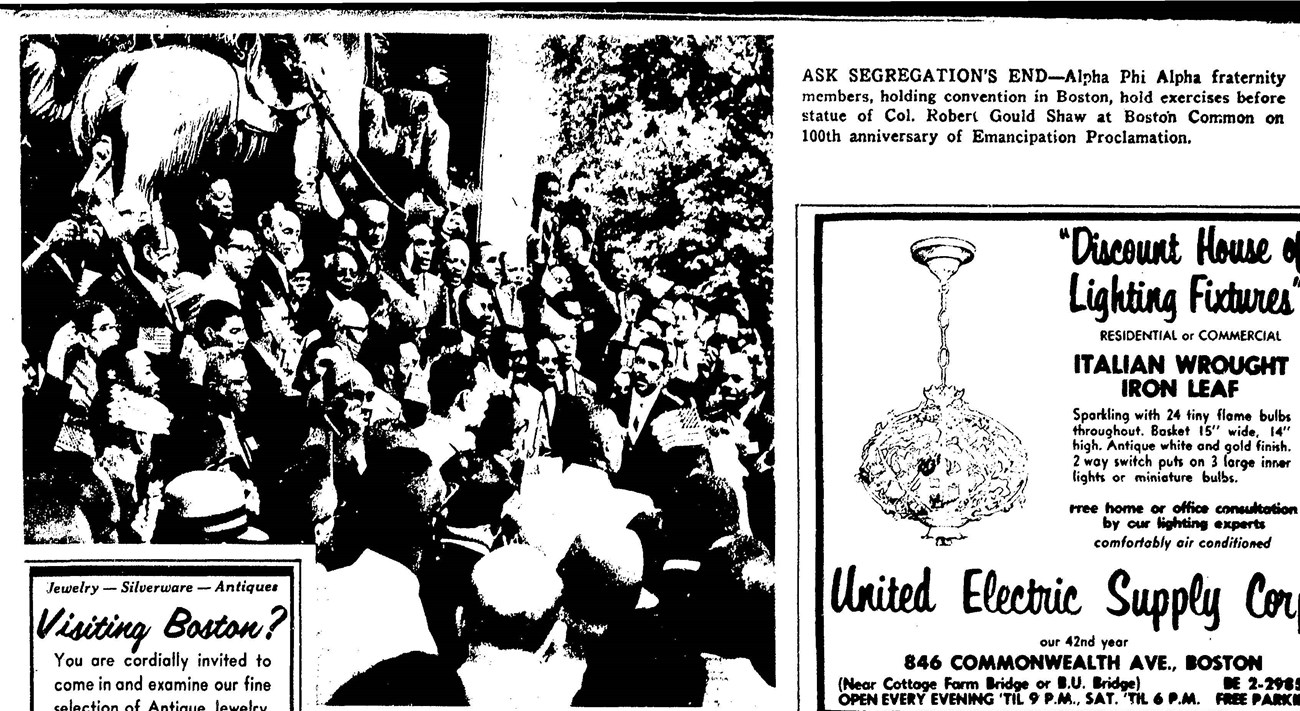

August 1963: "We Want Freedom Today"

In August, 1963, Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established for African Americans, met in Boston. To show solidarity with the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in its efforts to gain equal education:

500 fraternity members marched to Boston Common to the statue of Col. Robert Gould Shaw…the group paraded past the Boston School Committee on Beacon street in a protest against alleged de facto segregation in public schools here.[1]

Boston Herald, August 21, 1963

One paper described the event:

Waving small American flags, fraternity members said they were protesting in behalf of the local NAACP’s fight against school segregation. They also observed the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation in ceremonies before the statue of Col. Robert Gould Shaw.[2]

The fraternity's history director and president of Central State College, Charles Wesley, told the group, "We are having our call to arms to fight for freedom in the U.S…God help the rest of the nation if segregation can be carried on in Boston, the cradle of liberty…We want freedom today."[3]

June 1965: "So That Our Voices and Numbers Will Be Heard"

In 1965, Reverend Robert L. Pruitt of the Boston Ministerial Alliance issued a press release calling on "every responsible pastor and every thinking citizen of Roxbury" to meet "in front of the Shaw Memorial." Pruitt and others planned to march from the Memorial to the headquarters of the Boston School Committee to advocate for better educational opportunities. He said, "We will gather there in order to prepare our March on the School Committee so that our voices and numbers will be heard."[4]

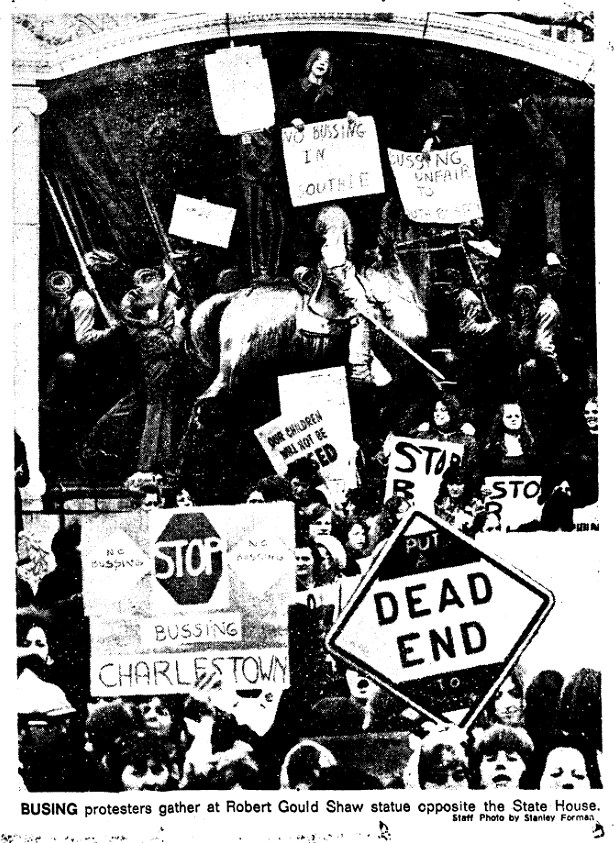

April 1973: Protesting the Racial Imbalance Act

Boston Herald, April 4, 1973.

As part of the battles that raged in Boston over school desegregation, thousands of demonstrators gathered on and around the Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial in April 1973 to protest the Racial Imbalance Law. This 1965 Massachusetts state law mandated racially balanced schools.

Many of the protesters came from South Boston, a largely White working-class neighborhood soon to be impacted by court-ordered busing. Leaders of the protest included former Congresswoman Louise Day Hicks, who said, "You will be criticized for your efforts by some, labeled bigot by others…But do not be discouraged."

This picture accompanying a Boston Herald article shows a number of White students and adults in front of and on the memorial itself holding placards reading "No Bussing In Southie" and "Stop Bussing Charlestown." Students at the protest vowed that "no black student will come into Southie."[5]

October 1979: The Backlash Continues

In 1979, as conflict continued in Boston over school desegregation, White students held a rally in which they hung a "White People's Rights" placard on the memorial. An article in the Boston Herald noted that the protesters:

had climbed all over the city's famous Robert Gould Shaw Memorial yesterday without apparently realizing that is a tribute to one of the nation's earlier instances of racial integration…It was all there for the students to read in clear letters on the statue, but they apparently didn't bother to do so. And they apparently didn’t notice that the troops behind Shaw on his horse were black.[6]

November 1979: "Love Thy Neighbor"

To help alleviate the ongoing and explosive racial divide in the city, particularly over the issue of busing, interfaith leaders held a "love thy neighbor" campaign in 1979. An estimated 4,000 people attended the ecumenical service. According to the Springfield Union:

In the shadow of a memorial to black Civil War soldiers on historic Boston Common, Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and Muslim leaders launched a drive for racial harmony in this troubled city.[7]

Springfield Union, November 20, 1979.

1981: A "Stirring Symbol"

In keeping with the move toward racial healing after years of unrest, as well as to rectify years of corrosion from acid rain and vandalism, concerned leaders in Boston formed the Committee to Save the Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial in the early 1980s. Co-chairman John D. O’ Bryant discussed the symbolism of the Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial in the context of a city divided over the issue of equal school access. He said, "The monument portrays something we all should be striving for – access, equality and an improved way of life." Another committee member, John T. Galvin, wrote:

No memorial in the United States symbolizes so vividly what the country should stand for, as the Shaw/54th Regiment monument atop Beacon Hill…the bronze and marble of the Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial gives us a handsome and stirring symbol of blacks and whites fighting side by side in a common human cause of the highest kind…the committee hopes Boston’s school children – both black and white – will learn what the monument stands for. The example set for us more than a century ago is one we can follow now.[8]

According to Henry Lee of the Friends of the Public Garden, which oversaw the restoration:

Our hope was that, in drawing attention to this, we could do a little bit toward healing some of our present conflicts. But we're not naïve. We don't suppose that tossing our little pebble in the pond is going to cause great waves.[9]

Conclusion

At the dedication of the memorial in 1897, keynote speaker Booker T. Washington said that the monument stood "for effort, not victory complete." He called people to further action by saying "What these heroic souls of the 54th Regiment began, we must complete."[10] Many activists in the 20th century education movement in Boston attempted to heed that call in their efforts at the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial.

Today, students and visitors from all over the world learn about the history of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment at this memorial that honors its legacy. This site also marks the beginning of the Black Heritage Trail, which explores the struggle for abolition and equal rights in 1800s Boston.

Please note, much of the information above first appeared as part of the National Parks of Boston’s online feature, The Ongoing March: Commemoration and Activism at the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial.

Overview Timeline Article

Black Struggle for Equal EducationFootnotes

[1] "We'll 'Catch Hell' Integrating Schools," Boston Herald, August 21, 1963. De facto segregation means that even though no legislation overtly segregated students by race, that it was nonetheless occurring.

[2] "Peabody Unit Urges School 'Rights' Study," Boston Record American, August 21, 1963.

[3] "500 in Fraternity March on Hub School Hqs.," Boston Traveler, August 20, 1963.

[4] Phyllis M. Ryan, "Roxbury clergy and citizens asked to march on School Committee on Monday night June 14th" (Boston, Massachusetts: School Committee of Boston, June 11, 1965), Northeastern University Library. This press release can be viewed online.

[5] "Sargent, White Fail to Meet Bus Protesters," Boston Herald, April 4, 1973.

[6] "History of Abuse repeated," Boston Herald, October 20, 1979.

[7] "Boston service launches 'love thy neighbor' campaign," Springfield Union, November 20, 1979

[8] "The Shaw Memorial: Stirring symbol of fighting together," Boston Herald, February 22, 1981.

[9] "For These Union Dead," Boston Globe, September 5, 1982, 33.

[10] The Monument to Robert Gould Shaw: Its Inception, Completion and Unveiling, 1865-1897 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1897), 69-70.