Last updated: January 23, 2025

Article

Volunteer Archivists Decipher Thousands of Untold Stories from the American Revolution

NPS

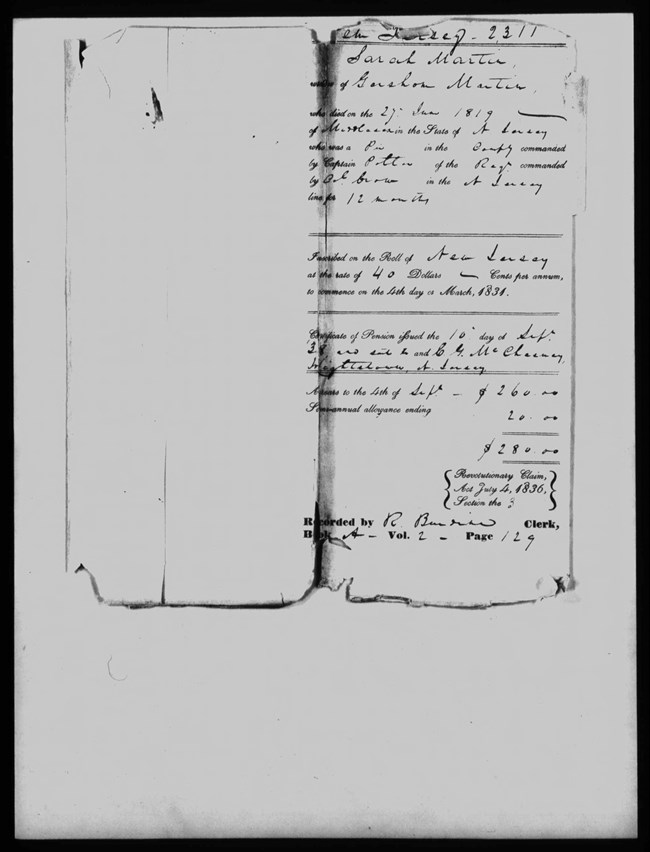

In 1777, drunken British soldiers stormed into Sarah Martin’s home in Woodbridge, New Jersey and demanded that she cook them ham and eggs. Hostile and impatient, the soldiers threatened to kill her youngest child, who cried as she prepared the meal. One of the officers even wielded his sword, striking the child and giving Martin a severe cut across the arm.

This appalling scene was not a unique event in Martin’s life. The family’s roadside residence, then in British-occupied territory, was ransacked as many as 30 times during the Revolutionary War. British soldiers plundered the home, drove away cattle, and eventually burned down the property while her husband, Gershom Martin, was away for months at a time on militia duty.

Martin recalled these traumatic events 60 years later in a court of record. The 83-year-old widow had to provide oral testimony about her husband’s military service to demonstrate her eligibility for a pension. Today, her story is one of more than 80,000 that would remain untold if not for the Revolutionary War Pension Project.

The Revolutionary War Pension Project is a collaborative effort between the National Park Service and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to transcribe more than 2.3 million pages of pension files from the nation’s first veterans and their widows. Launched in June 2023, the citizen archivist mission provides volunteers with the opportunity to make a permanent contribution to the historical record as the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence approaches.

This appalling scene was not a unique event in Martin’s life. The family’s roadside residence, then in British-occupied territory, was ransacked as many as 30 times during the Revolutionary War. British soldiers plundered the home, drove away cattle, and eventually burned down the property while her husband, Gershom Martin, was away for months at a time on militia duty.

Martin recalled these traumatic events 60 years later in a court of record. The 83-year-old widow had to provide oral testimony about her husband’s military service to demonstrate her eligibility for a pension. Today, her story is one of more than 80,000 that would remain untold if not for the Revolutionary War Pension Project.

The Revolutionary War Pension Project is a collaborative effort between the National Park Service and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to transcribe more than 2.3 million pages of pension files from the nation’s first veterans and their widows. Launched in June 2023, the citizen archivist mission provides volunteers with the opportunity to make a permanent contribution to the historical record as the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence approaches.

NPS/Kristin Vinduska

A Treasure Trove of Stories

Many of the soldiers who survived the American Revolution were left in poor health. In the decades that followed, they often struggled to work and support their families. The young United States addressed this burgeoning crisis of poverty among Revolutionary War veterans by passing the first of four pension acts in 1818. The youngest veterans were in their late 50s and 60s at that point, burdened by 35 years of economic hardship after the war ended in 1783. Several of them owned little but the clothing on their backs and were in desperate need of financial assistance.At first, pensions were only available for Continental Army soldiers who served under George Washington. Later acts opened pensions to those who served in militias and to widows, like Sarah Martin, married before the war’s end. Since there was little documentation to support the eligibility of widows and militiamen, these applicants had to describe their wartime experiences in a court of record and verify the details with credible witnesses. For a lot of them, especially for those who couldn’t write, it may have felt like the only chance to document their stories. The testimonies of women and people of color fill important gaps in the historical record and reveal the diversity of people who contributed to the war effort.

In the 1970s, NARA created thousands of microfilm reels with photographs of Revolutionary War pension documents held in the National Archives building in Washington, DC. The content of these reels was later digitized for NARA’s online catalog. The collection contains both handwritten pages and later-typed correspondence about the pensions with quality ranging from intact and easy to read to torn, covered in inkblots, and illegible.

National Archives and Records Administration

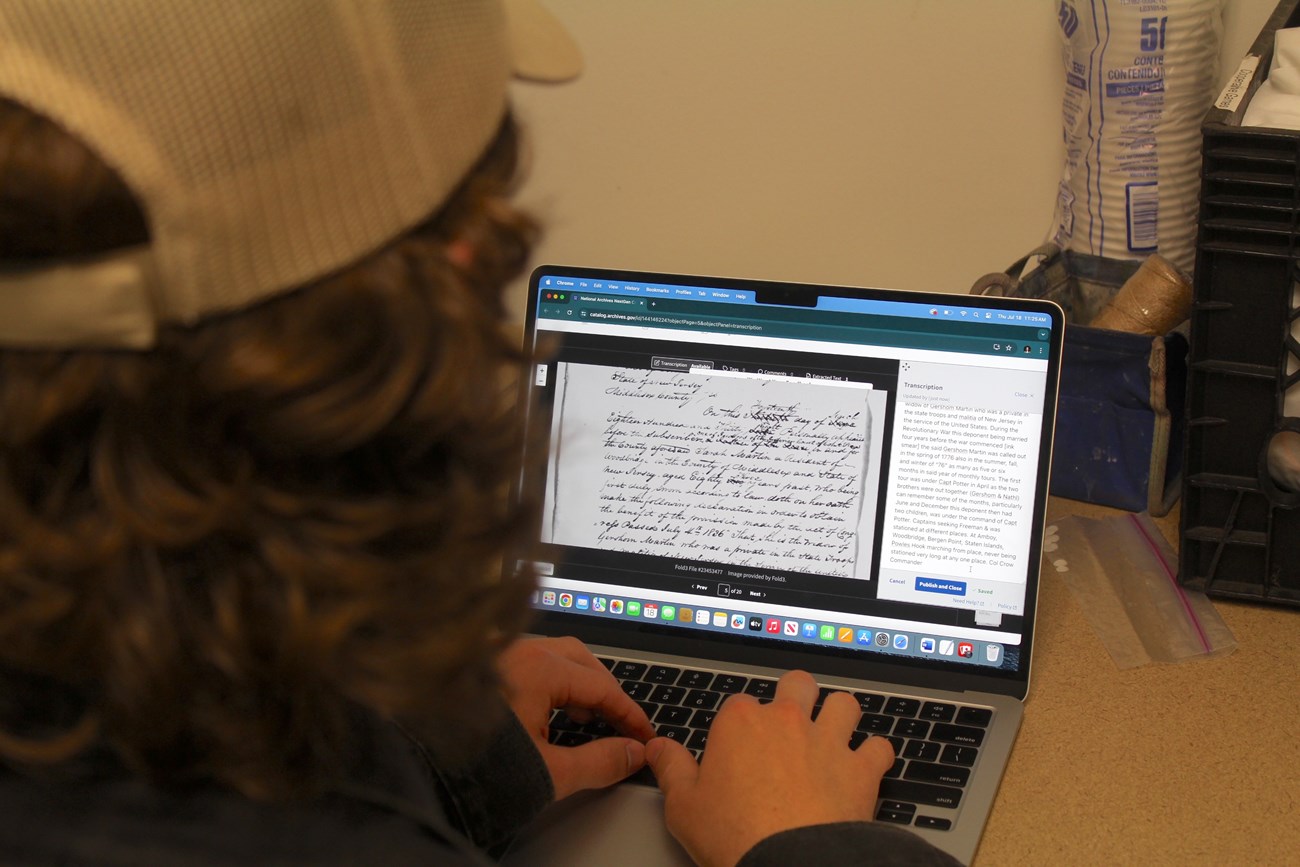

To date, more than 4,000 Revolutionary War Pension Project volunteers have typed up the content of over 80,000 pages of pension files, with upwards of 2,300 records completely transcribed. Almost 600 contributors are from the NPS.

A Battalion of Citizen Archivists

The partnership between the NPS and NARA builds upon the strengths of both agencies. NARA’s archival collection of more than 13.5 billion items is brimming with records about historic sites that are protected and preserved by the NPS. The Revolutionary War pension applications have ties to a variety of these sites, from the grounds of the first battle at Minute Man National Historical Park to where the last battle took place at Colonial National Historical Park. NARA’s catalog will keep the pension files publicly available in perpetuity.“We wanted something that was going to last beyond an anniversary, not just in our own archives but in a place that everybody could access,” said Joanne Blacoe, an interpretation planner in the NPS’s Northeast Region who helped to develop the project.

NPS

“The pensions are revealing the stunning — frequently heartbreaking and sometimes funny — complexity, nuance, and previously unknown details about the American Revolution and the nation in the decades after,” said Blacoe. “It's rich content that will benefit parks and inspire artists, researchers, and families connecting to ancestors.”

Public involvement is key to interpreting such a large volume of documents; historians could only transcribe a small fraction of the collection if they worked alone. Through NARA’s citizen archivist missions, members of the public have transcribed, tagged, and commented on tens of thousands of pages of records. Every contribution to the catalog becomes searchable, making it easier for researchers, educators, and others to discover relevant primary source materials.

Anyone can sign up to transcribe their choice of pension files on NARA’s website, but some national parks have organized site-specific transcription efforts. Guilford Courthouse National Military Park is recruiting volunteers to transcribe the pension records of veterans who fought at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in 1781, hoping to broaden the stories told at the park beyond the battle. The records tell more than just military stories, describing the lives of veterans after the war — what life was like in the new nation they created.

Several of the park’s volunteers are motivated by a love of history or a sense of volunteerism. Others have been able to connect with their ancestors who fought the British at Guilford Courthouse by transcribing their pension records. College-aged volunteers from around the nation are gaining professional experience working with and transcribing historic documents. The stories they bring to light will inform new education programs and museum exhibits at the park.

“New stories are being uncovered every day, and from the park's standpoint, that is extremely exciting,” said Daniel Engelgau, a ranger and volunteer program manager at the park. “Some of these volunteers may never come to Guilford Courthouse Military Park, but they will forever be a part of the park’s history due to their contributions to this project.”

Technology Meets the Human Eye

Citizen archivists offer an essential tool for transcribing historical records: the discerning human eye. NARA has access to technologies that convert the text of a digital image into text that can be read and searched by a computer, and the capabilities of artificial intelligence expand with each passing day. But these advancements have their limits, explained Suzanne Isaacs, a National Archives Catalog community manager. “Handwriting varies so much. Our records have been folded. They’ve been ripped. They have things written on the side and stamps that bleed through. Human eyes are better,” she said.

National Archives and Records Administration

Tags also make it easier for the NPS to identify stories with ties to the historic sites under their stewardship. For example, the pension document describing soldier David Hunt’s service in the Continental Army at Valley Forge has been tagged with “Valley Forge National Historical Park.” With such tags, parks can populate their websites with relevant records, and rangers can incorporate these captivating narratives into park tours.

Linking Past and Present

The Revolutionary War Pension Project expands the history of the American Revolution, opening up whole new areas for study. For example, historians can use pension files to draw connections between the lives of veterans past and present. Pension acts were passed in response to an epidemic of homelessness and poverty among the veteran community — issues still relevant today. Though separated by more than two centuries, present-day veterans share many feelings with Revolutionary War soldiers, from the boredom and frustration of deployment to the joys and challenges of coming home from combat.

The initiative also brings attention to lesser-known experiences of women and people of color such as Judith Lines, a widow whose pension application from 1837 contains the only known surviving letter written by a Black Continental soldier; Lewis Hinton, who took the place of his enslaver in the war; and Richard Leet, who obtained his freedom from slavery by becoming a midshipman on the frigate Alliance.

Educators can use pension files as primary source material in the classroom. Genealogists can tap into social history details to better trace family lineages. Artists and writers can glean insights into the day-to-day experiences of America’s first veterans and their families.

“For students, for teachers, for any kind of researcher, you get a more thorough and nuanced sense of what was happening — much more than you would get from a textbook,” said Nancy Sullivan, another community manager with the National Archives Catalog. “It brings the revolution to life in a way that nothing else I’ve seen does.”

Educators can use pension files as primary source material in the classroom. Genealogists can tap into social history details to better trace family lineages. Artists and writers can glean insights into the day-to-day experiences of America’s first veterans and their families.

“For students, for teachers, for any kind of researcher, you get a more thorough and nuanced sense of what was happening — much more than you would get from a textbook,” said Nancy Sullivan, another community manager with the National Archives Catalog. “It brings the revolution to life in a way that nothing else I’ve seen does.”

NPS/Nina Foster

With the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence just two years away, you can have a similar experience and expand our knowledge of American history by registering to transcribe or tag these invaluable records. Add “NPS” to the beginning of your username when you register with NARA to be counted as a National Park Service referral. Read carefully for references to NPS sites — you might be the first to encounter a national park that hasn’t been mentioned in other transcripts.

Written by Nina Foster, a 2024 Scientists in Parks intern at Acadia National Park. Nina is exploring her professional interests in writing about people, places, science, and history.