Last updated: July 12, 2023

Article

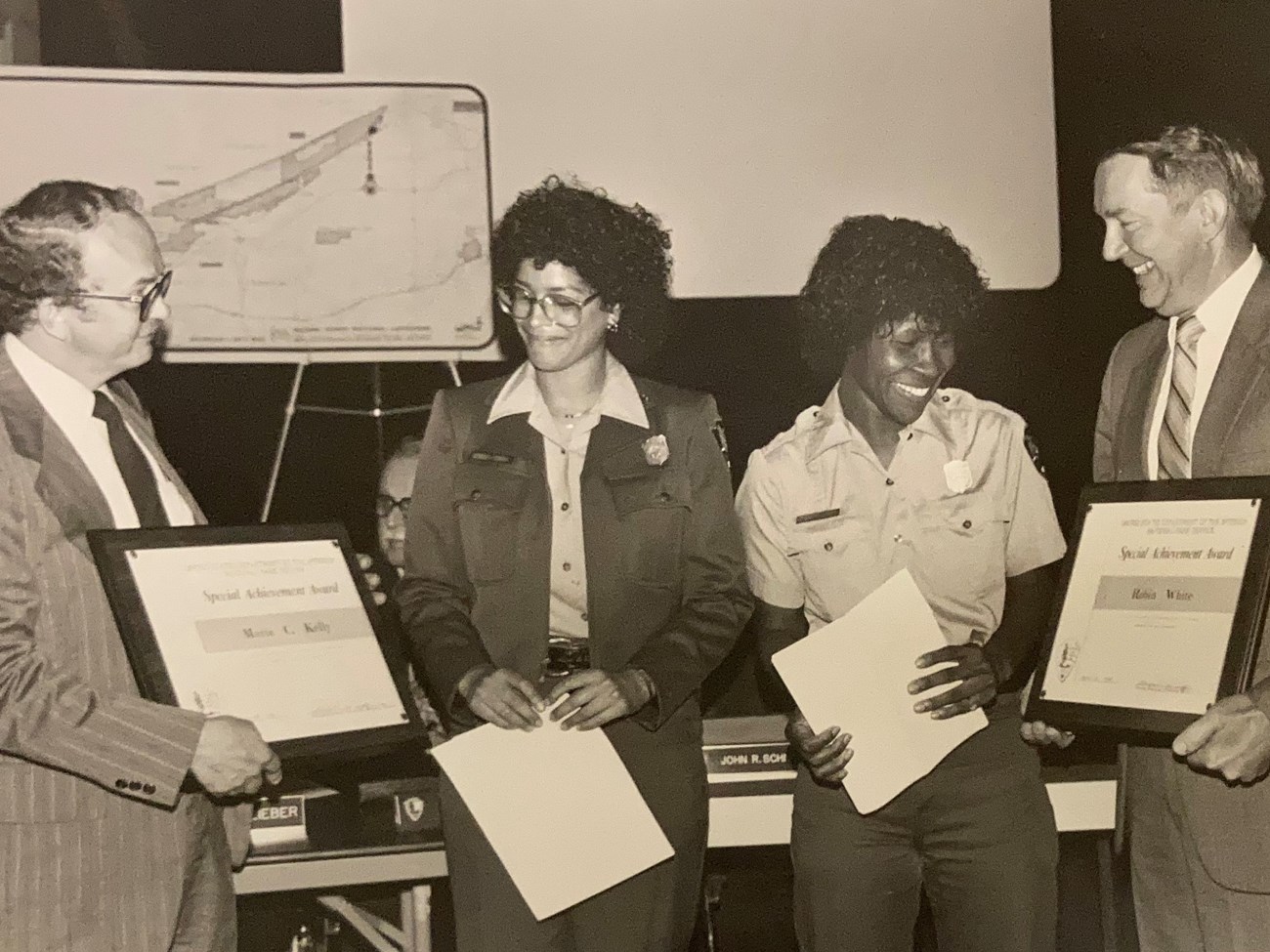

Robin White

At age 11 Robin White lost her mother. She lived from place to place and state to state under the rule of many matriarchs. Known in the family as the “suitcase kid,” White grew up knowing that “there was so much love around me, particularly with the women.” She spent her childhood moving between foster homes, a girls’ school, and various family member homes in Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. White recalls that formal education wasn’t a priority but “they educated me in other ways. Learning about family is absolute—my job is to serve the community because everywhere I go, I belong.”

Her Mississippi family taught her about native plants and tried to instill in her the place Black people were expected to occupy in the South in the 1970s. In a 2020 oral history interview, White notes that they were “trying to teach me how to survive, how to survive with white people. I had to learn how to navigate in the white man’s world. I had to behave and carry myself humbly and not draw any attention at all to myself or others.”

White had trouble following a different set of rules; she was inquisitive as she tried to understand the silence.

I still had to look down and not look white people in the eye, nor back talk. “Yes, ma’am, No, ma’am” was an automatic response. You just didn't question adults and I was always questioning. My family had an unspoken fear for me—sometimes you could see concern in their eyes. I could feel it when their gentle hands cupped my face and looked deeply into me. They said that I was a wild child, that I was going to bring death to myself. I didn’t know how to back down.

White felt the injustice of racial inequality.

Why do I have to keep my head down or step off the sidewalk for white people to pass? We had to look down or try to be invisible. What do you mean we’re not worthy [or are] unintelligent? I am not a bad person, a criminal, or just a nobody. The tough lessons were for me to love myself, [not] wait for the approval of others. Why was I not good enough? Why was I devalued? Why do I have to move over for the good people? If they’re good people, then what does that make us? I constantly questioned at age twelve, thirteen, fourteen, trying to wrap my head around the two worlds.

White would later transform her “invisibility” and perfect this attribute through her work with the National Park Service (NPS) working behind the scenes in service to her community. White feels that “everywhere she goes she is part of that universal community.”

At the same time, she could still display a child’s innocence, believing that the Colored water fountains were “a trick because no colored water came out of the water spout.”

White learned to navigate in a third sphere as part of the Gullah Geechee community when she moved to live with family in South Carolina.

It was not popular to be of the Gullah Geechee culture. I learned at an early age to become invisible when white people used to say to me, “Come here, you little ole nappy-headed Geechee girl.” I’d hide my pain and swallow the hurt. When others called me a Geechee girl, it was filled with love and pride. But the way white people said it, it was like being called the N-word. Their harsh tone alone would let you know that it was nothing nice. I didn’t have to look up to see the hate in their eyes; I heard it in their voices.

Despite those terrible experiences, White is thankful for her Gullah Geechee heritage, remarking that “those wise women immersed me in tangible and intangible lessons that remain a part of me to this very day. I am grateful for their heart and hands as they nurtured and cultivated me.”

White grew up loving nature and the outdoors: “I’m the one that would run and pick up a snake. I’m the one that would come back with the frogs, with the animals, and run in and out of the house. I’ve always been the child that was a part of nature.” Lessons in her cultural heritage and experiences such as catching crabs and shrimp, picking pecans and cotton, and learning about waterways were her education of choice and necessity. White dropped out of school after the ninth grade.

Later in life, White returned to formal education. At 19 she earned her GED. She went on to earn a BS in criminal justice from Indiana University Northwest. Later, she completed a master’s degree in leadership, social issues, and public policy at Union Institute University. As of 2022 she was pursuing a doctorate in theology and divinity.

White was 22 years old and living in Michigan City, Indiana, when she enrolled in a workforce development program through the Young Adult Conservation Corps. Part of the training included role-playing job interview techniques. She was partnered with Sam Vaughn, the environmental education coordinator at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. He asked her how she would feel about working with white people. She responded, “Content. Why? What’s wrong with that? You’re no better than I am.” She recalls, “He burst out laughing and said, ‘We’re going to hire you.’ I didn’t believe him.” She received a phone call a few weeks later telling her to report to the maintenance division at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.

Her career in maintenance was short-lived. She was supposed to work in road and trail maintenance, but as she put it, “They had a problem with me because I kept running off looking at plants.” She was soon transferred to the park’s environmental education program as a park aide. She had no professional training or background in the field but had lots of life experience living and working in different environments.

She recalls, “At first it was me, Bernadette Williams, and Marta Kelly, three girls of color and different shades. Then Darlene Mandel-Carnes joined us. She was a happy white girl from Michigan, always laughing, full of light and love. She was very supportive of us.” Not everyone was as open minded. White remembers that “the police used to follow us from Beverly Shores. Larry Waldron, the chief of interpretation, told them he will call the FBI in if they didn’t leave us alone. They saw us so much that eventually they got used to us.”

In addition to presenting environmental education programs, White was the park’s urban coordinator. She developed an urban transportation reimbursement program and began family day programs to bring more families to the park. She worked with rival gangs in Gary, Indiana, and Chicago. She recalls that she, Williams, and Kelly could go into Cabrini Greens and other Chicago-area public housing projects when the police couldn’t:

We came up with different ways to empower the community. We initiated Black history programs, but we took them into Chesterton, Porter, and Portage, Indiana. We used what methods and means we had to empower other communities that didn’t look like us, by sharing our stories, our narrative with them, for them to see us as human beings and to diminish social and cultural barriers.

While working at the park, she dedicated her free time to learning Spanish and sign language, writing, and studying natural and cultural history. She did all of this while raising her own family.

In spite of her success at Indiana Dunes, White soon found that her career would be limited there.

When I wanted to go into law enforcement to become an LE ranger it was clear that I wasn’t fully accepted at the park. One insult was, “You think we would put a gun in your hand?” I was young, but it stayed with me because I [couldn’t] figure out what that meant. I didn’t understand. What are you saying, putting a gun in my hand? I had a better relationship or rapport with the urban communities than they did and I was beginning to make traction with the white communities.

As many of her coworkers moved on, White decided it was time for her to do the same. She reflects, “I felt like I’d grown into a better me that wasn’t appreciated.” After almost 10 years at the Indiana Dunes, she accepted an education specialist position at Petroglyph National Monument.

From 1991 through 1995, White developed education programs at the park and in schools in New Mexico and Colorado. She worked with other federal and state agencies, The Five Sandoval Indian Pueblos, and the Southern Ute Tribe to reach a wide range of children. In 1993 she received a $150,000 grant to develop the Parks as Classrooms program at Petroglyph. The grant allowed White to produce two award-winning teachers’ curriculum guides.

Her experience at Petroglyph was very different from Indiana Dunes.

I think they enjoyed just watching me navigate my way through, getting groups out and using different methods to promote the National Park Service. They just watched me and let me grow. Whatever I was trying to do, they believed in me and just like Indiana Dunes allowed it to happen. Whatever training [I needed], they invested in me.

In 1995 White was recruited by the superintendent of Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site to serve as education specialist and chief of interpretation. As part of the management team, she helped to stand up a new park. Her duties included participating in park planning, recruiting staff, developing partnerships, writing grants, developing education programs and exhibits, and collaborating with other organizations for an annual symposium on the anniversary of the Supreme Court decision.

White continued her work to help establish new NPS units when next recruited to New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park. She and other park staff developed a jazz concert series, musician camp with Winton Marsalis and other musicians, and partnership with Amtrak that saw musicians playing on trains from New Orleans to Chicago, among other projects.

White also completed an international detail to Kruger National Park in the Republic of South Africa in 1998 and then became a supervisory park ranger at Grand Canyon National Park. She recalls arriving at the park:

What was striking is that we didn’t have any Native Americans in our interpretation division. They all worked in maintenance. So I talked to my superiors and my chief of interpretation. We ended up hiring two. Rex Tilousii from the Havasupai tribe did cultural demonstrations, and Phyllis, who was Hopi.

White found that the park’s relationship with the locals was strained. She established partnerships with local businesses and collaboratively won a $418,000 grant to fund community events in northern Arizona. Over time, she made inroads with some communities but got pushback from other NPS employees, particularly law enforcement rangers. During a presentation on diversity, invited Native American guests spoke of being profiled by park law enforcement rangers, and “it got really serious. I made a few enemies. I was actually threatened.”

The superintendent had to intervene. White remembers, “I was told to watch myself on the Rim. Someone broke into my house. I hosted dinner parties. A law enforcement officer would sit out in front of my house, and I’d give them a plate each time. Eventually, they began to see me.”

In 2002 White was the first recipient of the NPS Intermountain Region Franklin G. Smith Award honoring her civic engagement and diversity work. Although she built relationships with local communities and won awards, White continued to experience a lack of respect from some park staff, including the chief of interpretation. She enrolled in a Department of the Interior (DOI) leadership training program for which she says the park eventually grudgingly paid. As part of the program, she completed assignments with the National Park Foundation in Washington, DC, and the Harriet Tubman Research Study Project. The situation didn’t improve when she returned from the training program, so she decided it was time to move on.

After being at Grand Canyon National Park for seven years, White became superintendent at William Howard Taft National Historic Site in July 2005. She focused a great deal of energy on connecting with the local community who had never visited the park. She hired musicians to perform and attract crowds, started a Victorian fashion show to illustrate the clothing styles worn during Taft’s time, hosted lecture series, and created public programs on gardening, fencing, and other topics where they could connect to Taft’s life or legacy. Her first year, park visitation increased from 1,500 to 4,500. The next year, it was over 60,000. In her oral history, she explains how she considers music as well as food to be important assets to building community connections since both are important to all people.

While she enjoyed the work, she was not a fan of the cold weather. After three years, she was ready to go farther south. In August 2008 White moved to Arkansas as superintendent of Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site.

White continues her practice of community engagement. At Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site, she has developed numerous partnerships with local, state, national, and international organizations. Under her direction, the park created a Youth Leadership Academy designed to develop student leaders, raise consciousness in local communities, and encourage creativity in the education of civil and human rights for high school students. She explained her approach.

I think that in the Park Service, it’s not our responsibility to push our mission upon people. Because when we develop a relationship with them, they will learn our mission and it will organically grow and they will become involved. This is what’s been happening here in Little Rock with the young people developing programs addressing social issues.

In 2017, White also engaged in conversations regarding the Black Lives Matters movement. In an interview with KCBX, White said,

We have town hall gatherings. We’ve had a program called “Conversations of Color.” We had what we call a social conscious gathering where people came together and talked about religious divisions, economic inequality, the education system, and about how we can move forward.

As of 2022 White remained superintendent of Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site. She finds the site to be a source of inspiration for equity.

This site affords us the opportunity to discuss the consequences of humanity, the concept of spiritual violations, the degradation of segregation, and the struggle of a people. It is imperative that we are inclusive of all people. It’s imperative that we work with both our advocates and adversaries to share their narratives.

Sources:

National Park Service. (1986, August). “New Places.” Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, 31 (8), pp 26.

National Park Service. (2008, Summer). “Awards.” Arrowhead: The Newsletter of the Employees & Alumni Association of the National Park Service, 15 (3), pp 15.

National Park Service. (1995). “New Places.” Newsletter: Employees & Alumni Association of the National Park Service, 2 (1), pp 4.

Pers. Comm. Robin White to Nancy Russell. (March 10, 2022). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry Center.

Robin White interview by Lu Ann Jones. (2020, August 26, 28, and September 3). NPS Oral History Collection (HFCA 1817). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry Center.

Wilmer, T. (2017, February 15). A trip to Arkansas results in an emotional conversation about racism in America. KCBX. https://www.kcbx.org/community/2017-02-15/a-trip-to-arkansas-results-in-an-emotional-conversation-about-racism-in-america

Explore More!

To learn more about the history of women and the NPS uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS

This research funded in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.

Tags

- brown v. board of education national historical park

- grand canyon national park

- indiana dunes national park

- little rock central high school national historic site

- new orleans jazz national historical park

- petroglyph national monument

- william howard taft national historic site

- women's history

- african american history

- nps history collection

- nps history

- hfc

- brown v. board of education national historical park