Last updated: January 25, 2024

Article

Scientists Publish First Study of White Shark Population Trends off of California

Scot Anderson

Kanive et al. 2021

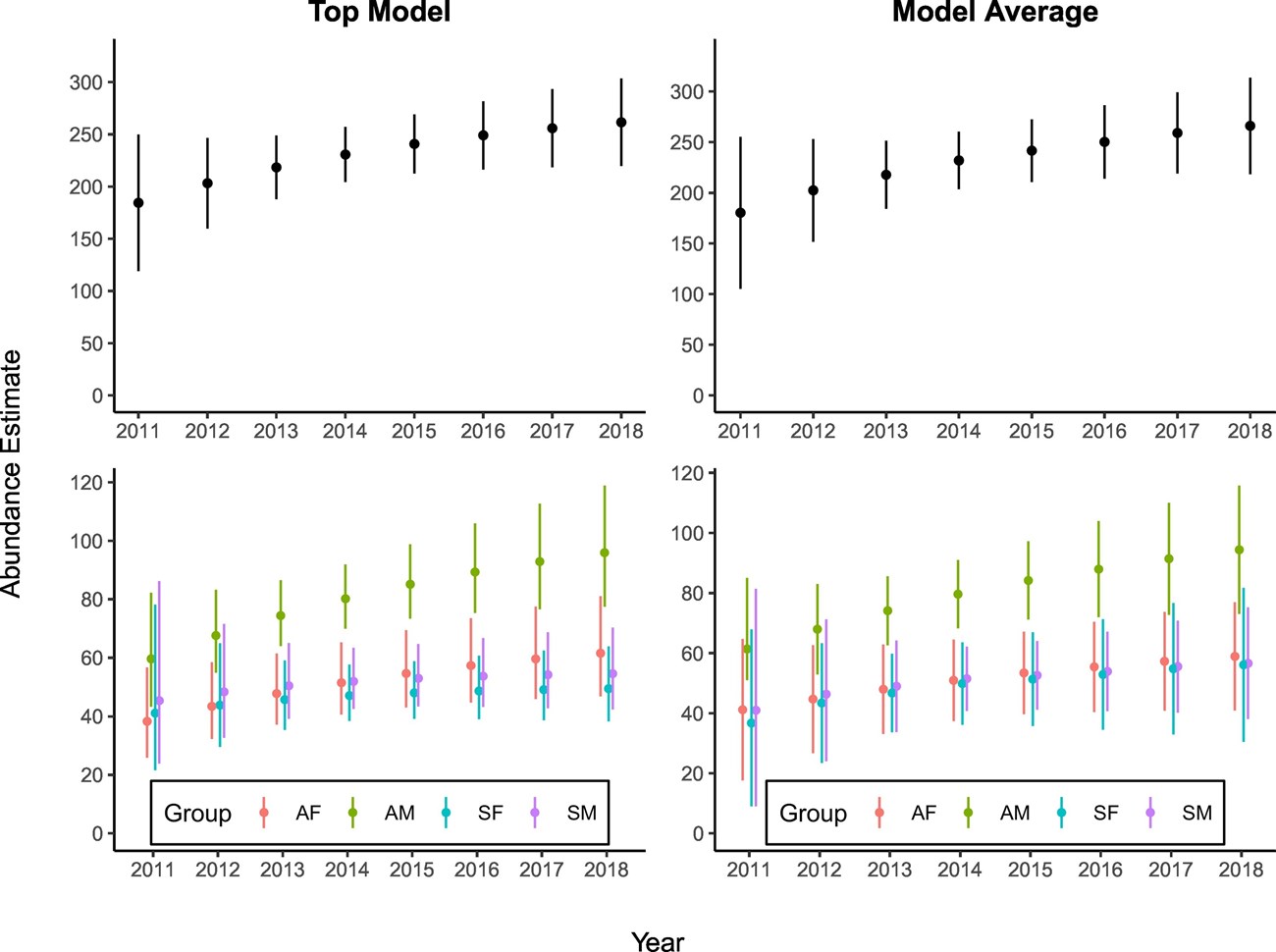

May 2021 - Great white sharks may not have fingers, but they do each have something akin to a fingerprint. The rear edge of their dorsal fins feature unique patterns that can be used to distinguish individuals. These patterns have been key to solving basic mysteries about central California's white sharks. For example, how many are there? For decades, marine biologists had no idea. They got their first estimate (~219) in 2011 from three years of photographing the sharks at their seasonal gathering spots, including off of Tomales Point in Point Reyes National Seashore. Looking back at the fin patterns to see how many known/unknown sharks turned up year to year enabled the calculation. But with no prior baseline estimate for comparison, another central question remained. How is the population changing over time? A team from Montana State University, the Monterey Bay Aquarium, and Stanford University collected eight years of photographic data to find out.

White sharks can live 70+ years and reproduce slowly. As a result, fishing practices and poaching can impact their populations in big ways. They may face other dangers as they migrate huge distances across the ocean. Central California sharks spend half the year far offshore in the northeast Pacific where high-seas fisheries are relatively unregulated. Yet going into their research, the marine biologists had cause for optimism. White sharks have now been protected in California waters since 1994. Coastal gillnets, which kill many juveniles as bycatch, have been banned since 1990. The Marine Mammal Protection Act signed in 1972 could also be helping central California’s white sharks. Seals and sea lions are some of the sharks' favorite prey species, and their numbers have been on the rise.

Kanive et al. 2021

Sure enough, the research team found modest signs of growth, at least in the adult white shark population. For sub-adults, the population appeared stable but it’s still too early to tell. Today's marine conservation policies may indeed be providing space for white sharks to succeed. That's good news not just for the sharks, but for the marine ecosystem that would be less resilient without it's top predator. At the same time, the total number of sharks is probably still below 300, and there may be only around 60 adult females. In other words, local white sharks remain vulnerable. Continued monitoring will be essential to making sure we don’t start going backwards. Additional research into white shark population dynamics and life histories will also be needed as we strive to become better white shark stewards. After all, figuring out numbers and trends is just scratching the surface!

For more information

- Kanive, P. E., Rotella, J. J., Chapple, T. K., Anderson, S. D., White, T. D., Block, B. A., Jorgensen, S. J. (2021). Estimates of regional annual abundance and population growth rates of white sharks off central California. Biological Conservation; 257: 109104. DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109104

- California Department of Fish & Wildlife White Shark Information & FAQ