Last updated: January 25, 2024

Article

eDNA Inventories to Reveal Species Use of Sonoran Desert Network Springs

Biologists have long sought to collect wildlife information in ways that are less invasive for animals and less labor-intensive for humans. Hair snares and remote cameras allow us to collect certain information about mammal populations in a non-invasive way—but it’s much harder to snag a scale off a fish, or deploy an underwater camera. With the help of gene-sequencing technology, however, it’s now possible for us to learn which species use a given area without capturing any part of an animal—not even its image.

SODN parks where eDNA inventories are being done:

Chiricahua NM | Coronado NMEM | Fort Bowie NHS | Gila Cliff Dwellings NM |

Montezuma Castle NM | Organ Pipe Cactus NM | Saguaro NP | Tonto NM | Tuzigoot NM

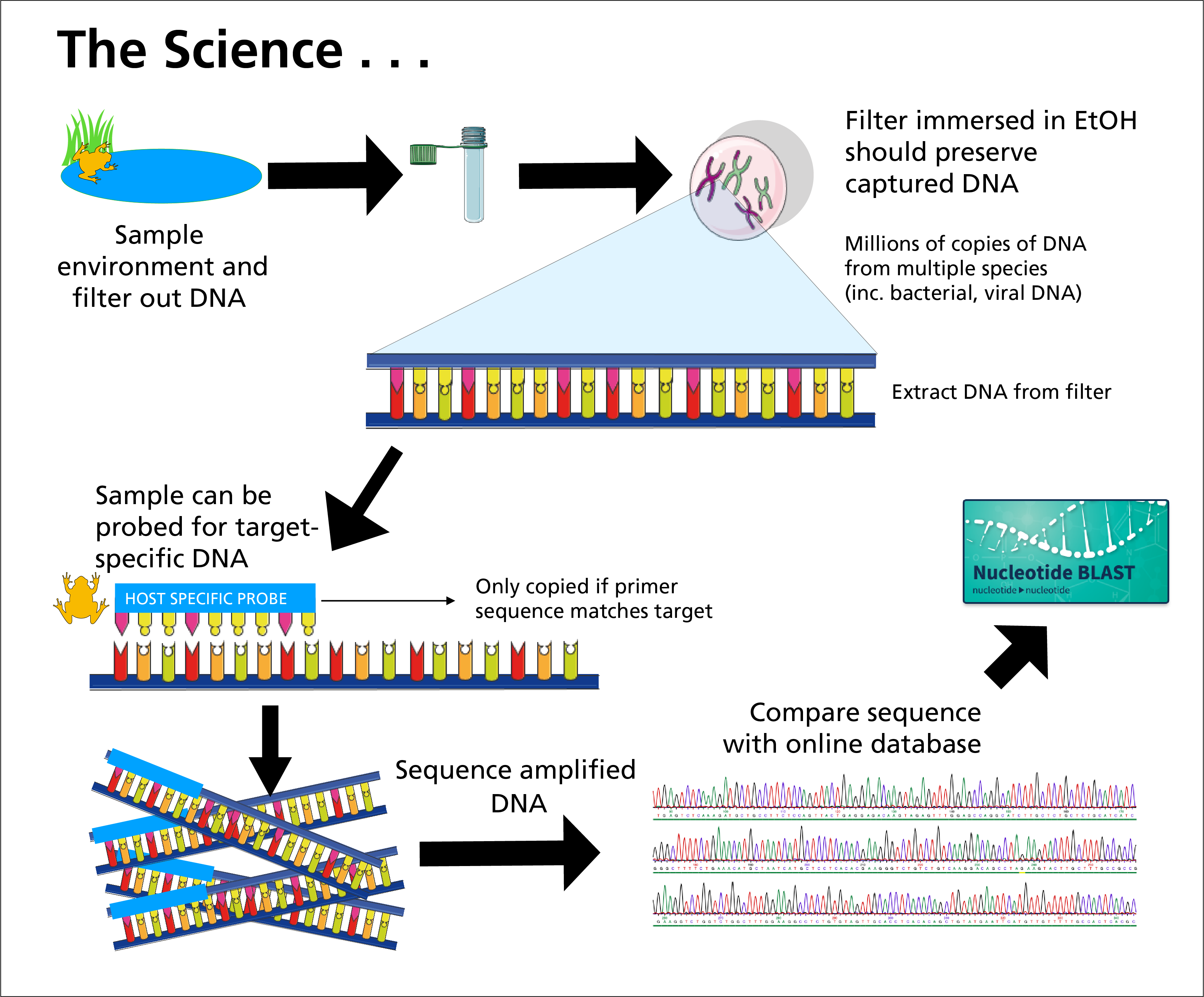

At nine Sonoran Desert Network (SODN) parks, our springs-monitoring crew is augmenting its usual monitoring with environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling. Using methods developed in part by IVIP Josh Richards (see photo gallery, below), we use a vacuum or peristaltic pump to move 250 mL of springwater (per sample) through a 0.45-micron filter. Then we extract and fold the filter using "clean room" techniques (yes "clean room," even though we were sitting on the side of a spring!), including disposable single-use filter sets, fresh gloves, and sanitized forceps for each sample. The folded filter is placed in a 2-mL vial of 100% molecular ethanol, then stored in a freezer until it’s sent to a lab at Washington State University.

The filters contain bits and fragments of DNA from any animal that’s recently used the spring. Fish. Mammals. Birds. Reptiles. Insects. Anything that is or was alive. At the lab, the samples are compared against known assays for genomes of interest.

Summary of the eDNA sampling process.

At SODN parks, we’re searching for genomes of seven species:

- Arizona jaguar (Panthera onca arizonensis, endangered, locally extirpated),

- Chiricahua leopard frog (Lithobates chiricahuensis, endangered/locally extirpated),

- lowland leopard frog (Lithobates yavapaiensis, in regional decline, but expected to be found),

- Mexican garter snake (Thamnophis eques, threatened),

- chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, an infectious threat to native amphibians),

- ranavirus (Iridoviridae, another threat to native amphibians), and

- American bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus, an invasive threat to native amphibians).

All animals need water to survive, making springs and tinajas ideal places to do this kind of monitoring. To date, 231 samples have been collected. In addition to our established monitoring sites, we are also sampling Quitobaquito Pond (Organ Pipe Cactus NM), Tavasci Marsh (Tuzigoot NM), and Montezuma Well (Montezuma Castle NM). Sampling will be repeated in the fall to increase detection probability, because DNA can be diluted/diffused in samples collected at times when there is more water in the system (e.g., spring).

Lowland leopard frog (Lithobates chiricahuensis. Photo by Dennis Caldwell.

Lowland leopard frog (Lithobates chiricahuensis. Photo by Dennis Caldwell.

This project is an inventory, integrated into regular monitoring processes. It’s exciting, partly, because it gives us a chance to do things we’ve always wanted to do, without increasing sampling effort. For instance, a special set of analyses will be done for Gila Cliff Dwellings NM, where we will also sample the Verde River in search of selected species that were common in the early 1970s but not detected during species inventories done in the 1990s: the Chiricahua leopard frog, three toads common to the region but not recently found at the monument, and the narrowheaded garter snake (Thamnophis rufipunctatus). Are some of these important species still present, but rare enough to have been missed in traditional field surveys? eDNA may provide the answers.

Also, when SODN vital signs were being developed, animal monitoring sampling was highly rated as a desired vital sign. But sampling animals is typically more difficult and expensive than sampling resources that don’t move around on their own, so we were initially unable to do that. Now, technology like remote cameras and eDNA are making it possible. By modifying protocols we already have, we can do more of what we wanted to do in the first place. We are also futureproofing: preserving some of the current samples will give us the chance to go back and test them for additional species later on.

The results of this inventory will be useful in several ways. They may impact which springs we monitor. If we detect something really important at a certain spring, it could become a higher priority for monitoring. The results may also help park managers prioritize springs for conservation based on which biota are there. And this information will allow us to contribute to general knowledge about which species are most common to which areas.

This project is supported by the Inventories program of I&M’s Fort Collins office. They purchased most of the equipment, funded the agreement with Washington State University (@$140/sample), and provided support for Tucson Audubon field staff to assist with data collection. One interesting wrinkle: the equipment used for sample collection is also widely used in covid testing, so supply chain issues have made for some challenges. The use of a hazardous material (ethanol) as a preservative also requires some pretty specific and complicated shipping procedures.

Other I&M networks are also conducting eDNA inventories, but SODN’s results will be some of the first. All seven of our target animals have existing assays, which makes results faster and easier to obtain than when an assay has yet to be developed for a species. In the future, the Chihuahuan Desert Network (CHDN) will replicate this work at springs. CHDN will also look for bullfrogs, chytrid fungus, and ranavirus, but will target slightly different species beyond that. Live capture of some species may be necessary for assay development.

For more information, contact Andy Hubbard.

Tags

- chiricahua national monument

- coronado national memorial

- fort bowie national historic site

- gila cliff dwellings national monument

- montezuma castle national monument

- organ pipe cactus national monument

- saguaro national park

- tonto national monument

- tuzigoot national monument

- american southwest

- animals

- science

- edna

- conservation

- inventories

- inventory

- inventory and monitoring

- science and resource management

- springs

- swscience

- sodn

- sonoran desert network

- species inventory