Last updated: December 5, 2023

Article

Ramadas of the Southwest

Can you imagine living in the desert before air conditioning existed? It’s part of most of our lives today, be it at work, at home, or in the grocery store. In terms of technology and urban engineering, things are very different in the Sonoran Desert today than they were 500 years ago. Residents of the Sonoran Desert today still deal with extreme temperatures and water scarcity – increasingly so, in fact. And while air conditioning can be an immediate solution to the heat, it’s not as perfect as it may seem. There are traditional ways of managing the extreme local climate that are worth exploring. At the Desert Research Learning Center (DRLC), we built a ramada modeled off the design of a wa:ato of local indigenous peoples to help us deal with the desert heat.

NPS/E. Schnaubelt

Indigenous Use of Ramadas

In the desert, where summer days reach over 110 degrees Fahrenheit, shade can mean survival. Finding relief from the powerful solar radiation can cool the body and protect skin from burning. While desert conditions are often inhospitable, people have lived in the Sonoran Desert since at least 5,500 B.C.E. Before there was air conditioning, indigenous peoples -- such as the Akimel O’odham and Tohono O’odham -- lived, traveled, and harvested food here.

To create shade in the desert, they built ramadas: four-legged, roofed structures without walls. In O’odham, a structure like this is called a “wa:ato” (pronounced WAH-a-to). What does the Sonoran Desert offer for long, strong building blocks to make a wa:ato? Mesquite, and the woody skeletons of saguaro and ocotillo. Wa:ato roofs were commonly made with ocotillo and held up by a mesquite frame. To tie these woody pieces together, people often used rope made from agave or yucca fibers.

The woody body of ocotillo, closely visible in the photo on the left, can be used as a building material, for structures such as the roof of a wa:ato.

Photos: NPS/E. Schnaubelt

Saguaro cacti don't look like trees, but on the inside they're wooden! In the photo on the right, the "ribs" are visible in the dead saguaro. These "ribs" are long pieces of wood that run vertically through the interior of a saguaro, holding it up.

Photos: NPS/E. Schnaubelt

The black trunk and branches of the mesquite tree are a key source of lumber in the desert. This strong wood has been commonly used in ramadas, houses, and fences.

Photos: NPS/E. Schnaubelt

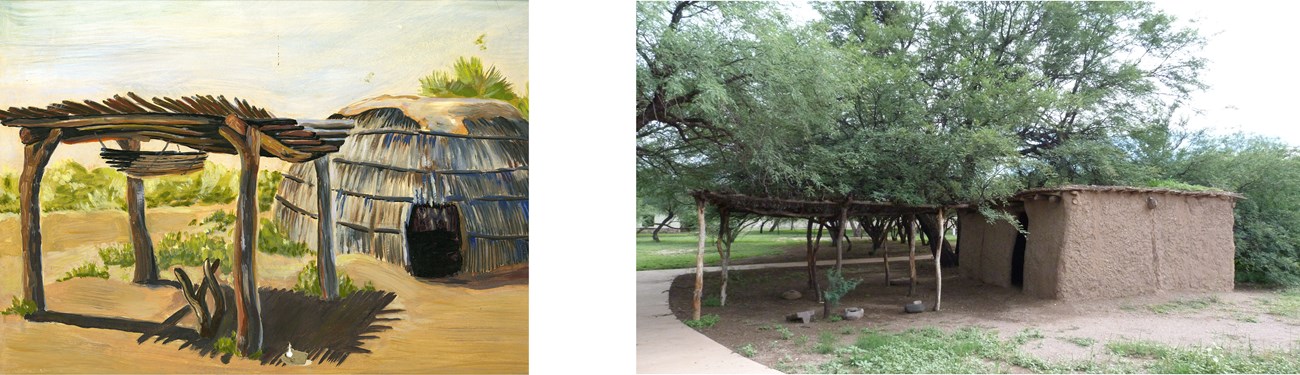

Historically, the lifespan of a wa:ato was about one season, though some were maintained as semi-permanent structures. They were often used to shade gathering spaces, such as markets or social events. A wa:ato was also used to create a shady outdoor extension of a house (or “ki” in O’odham). Because the insides of pit houses and puddled adobe houses were very hot in the summer due to their lack of windows, the open-air extensions were important to have. Many household activities took place outside under the wa:ato during the warm seasons.

Left: Courtesy of S’edav Va’aki Museum, City of Phoenix and the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration.

Right: NPS Photo

These ramadas were also used for shelter during travel and subsistence gathering. For example, the Tohono O’odham would construct a wa:ato to work, rest, and sleep under during saguaro harvesting. This minimized travel and allowed them to gather the fruit more efficiently while ripe.

Indigenous peoples still use the wa:ato design today, including two very visible examples inside national parks. Since the creation of Saguaro National Park’s Tucson Mountain District (TMD), the Tohono O’odham have continued their annual saguaro harvest practice. Working with the park, they built an enormous wa:ato in the TMD. Each June, family members in the tribe gather there for harvest and ceremony. Further south and in December, Tumacácori National Historical Park hosts an annual fiesta, in which park staff and volunteers participate in wa:ato construction to house around 50 booths for food and crafts, in celebration of indigenous and historically present cultures in the Santa Cruz Valley.

NPS/E. Schnaubelt

Our Ramada

The ramada at the DRLC is closely inspired by a wa:ato, with a few key differences. It’s comparable to a wa:ato in terms of size and appearance. It also uses ocotillo on top. But we wanted our ramada to be taller, longer-lasting, and require less maintenance than a wa:ato, so we freestyled a little to ensure a sturdier structure. Rather than using mesquite to make the frame and legs, our ramada stands on tamarisk trunks, which are thicker.

You may be thinking, “Hold on, I thought tamarisk is a nonnative, invasive species in the United States!” Well, you would be right! The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) was clearing tamarisk from the Buenos Aires Wildlife Refuge in Arivaca, Arizona, so we found a second purpose for it. This resolved our issue of not finding mesquite that was strong enough to support the ocotillo roof.

One last difference between our ramada and a historic wa:ato is that our structure is fortified with metal. The legs are lined with rebar and posted into a cement foundation in the ground, instead of the wood being staked directly into the earth. Indigenous peoples here did eventually have access to metal via trade with the south, but this metal was soft in type and in small quantities and valued for crafting adornments and jewelry; they wouldn’t have used it in architectural structures such as a wa:ato.

DRLC staff are currently constructing a second ramada, much larger than the first. Like the first, it will use ocotillo for its roof and the frame will be a mixture of mesquite and other material salvaged from cleared invasive plants. This new ramada will shade a second gathering space to be used for an agave restoration project and outdoor education programs.

NPS/E. Schnaubelt

NPS/E. Schnaubelt

Food for Thought

The Akimel O’odham and Tohono O’odham practiced what archeologists call “vernacular architecture”—the use of regional materials to respond to an environmentally influenced need of society. In their case, the environment of the Sonoran Desert made shade—as opposed to waterproofing, or insulation against the cold, a high priority. The regional materials were ocotillo, mesquite, and saguaro ribs. At the DRLC, the decision to reinforce our traditional ramada with locally sourced materials that met our needs for strength and endurance (tamarisk and metal) was in keeping with the spirit of the wa:ato—and the vernacular architecture they represent.

There are lots of good reasons to embrace vernacular architecture. First, it’s an environmentally sustainable design practice. When the built environment works together with the natural environment, less energy is required to make the climate suitable for humans. In Arizona, this means using less air conditioning, which allows us to both spend less money and reduce the amount of carbon dioxide and ozone-damaging refrigerants called chlorofluorocarbons we’re releasing into the air. Prioritizing the use of regional materials cuts down on transportation distance, thereby reducing associated emissions of greenhouse gases and particulate matter. And while addressing climate change goes far beyond modifying our individual actions, our own actions—and mindset—are a place to start when advocating for the broader changes that will be necessary to make a difference.

Constructing our spaces to be more in harmony with the environment can also strengthen our sense of unity with the planet, and our sense of place. Designing our spaces and systems to be an extension of their physical environment, rather than prioritizing convenience and standardization, helps us live in the awareness that everything is connected and interdependent—humans and the environment, humans and humans. In a world yearning for enhanced connections, this can be a place to start.

Among the many possible routes to improving our sustainability, emphasizing connectivity and creating unique climate solutions that depend on the regional environment go hand-in-hand. In this, there’s a lot of insight to be gained from looking to the practices of people with many centuries of experience living in, and adapting to, a given landscape—too often, practices and voices that have historically been marginalized are those that can provide crucial lessons as we confront climate change.

If you’re interested in what else makes the DRLC unique, follow the virtual tour to explore our grounds.

Prepared by Elizabeth Schnaubelt (Scientists-in-Parks intern) and Sharlot Hart (Archeologist).

NPS/E. Schnaubelt