Last updated: July 15, 2024

Article

The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society

Boston Public Library Rare Books Department

If this is the last bulwark of freedom, we may as well die here, as any where. – Maria Weston Chapman

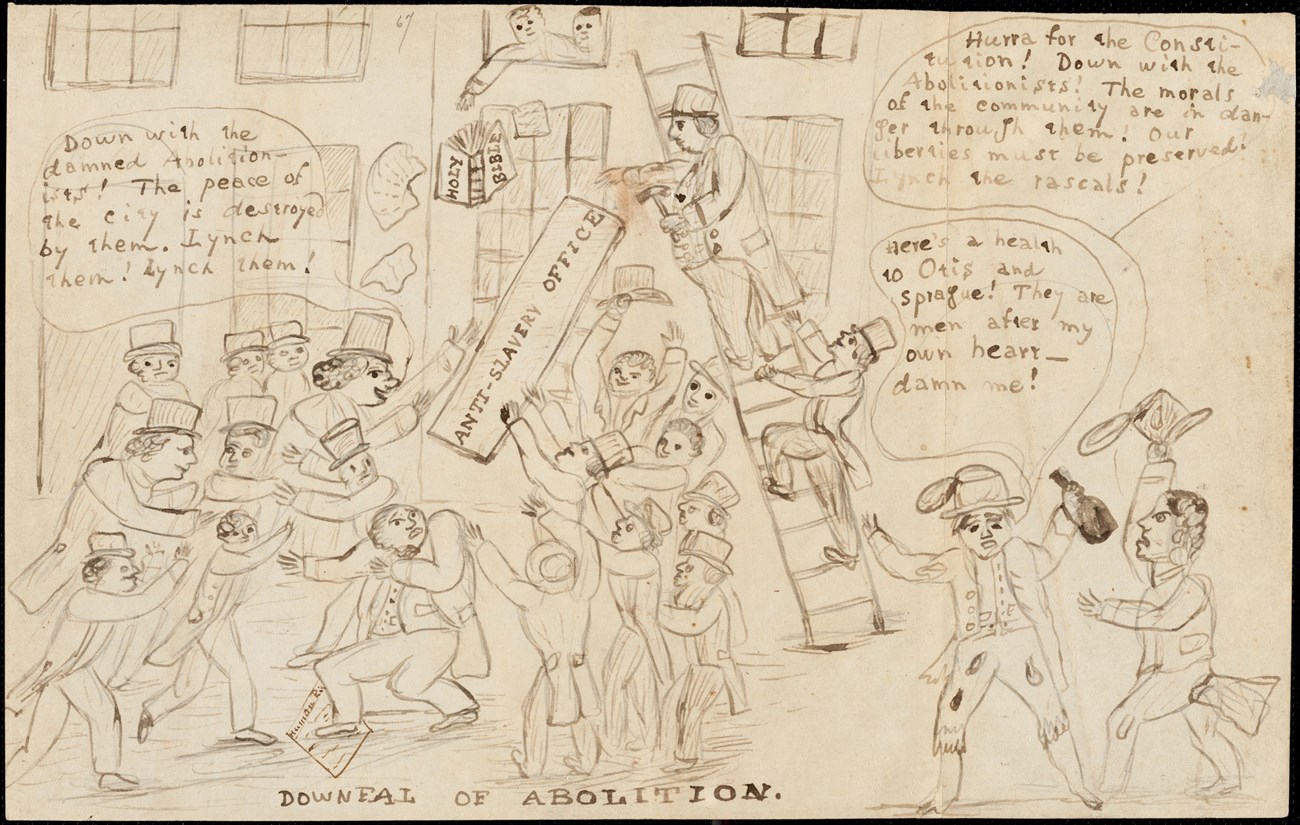

On October 21, 1835, a violent, angry mob disrupted the annual meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Spurred on by the anti-abolitionist rhetoric of community leaders and a willing press, this mob of "gentlemen of property and standing" gathered outside of 46 Washington Street where the women met. They intended to "lay violent hands" on British abolitionist George Thompson who originally planned to address the meeting.[1] Though Thompson had left, the mob turned its ire on local editor, William Lloyd Garrison, who offered to speak in Thompson’s place. The mob assaulted Garrison and dragged him through the streets by a rope. When the mayor implored the women to end their meeting and go home, Maria Weston Chapman said, "If this is the last bulwark of freedom, we may as well die here, as any where.[2]

Boston Public Library

Instead of canceling the meeting and dispersing, the women bravely defied the mayor and the mob and marched arm in arm from the anti-slavery office.[3] Amidst insults and threats, they proceeded to the home of one of their members and continued their meeting as planned. As one of the women observed:

If the worst enemies of some we saw, had told us that such unmanly and shameful ideas as they openly expressed, lurked in the most hidden recesses of their minds, we should have disbelieved it. The way was darkened by the crowd that blocked up the windows...When we emerged into the open daylight, there went up a roar of rage and contempt, which increased when they saw that we did not intend to separate, but walked in regular procession...[4]

Though their courage and actions that day launched them into national prominence, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society had been active for several years prior.

Beginnings

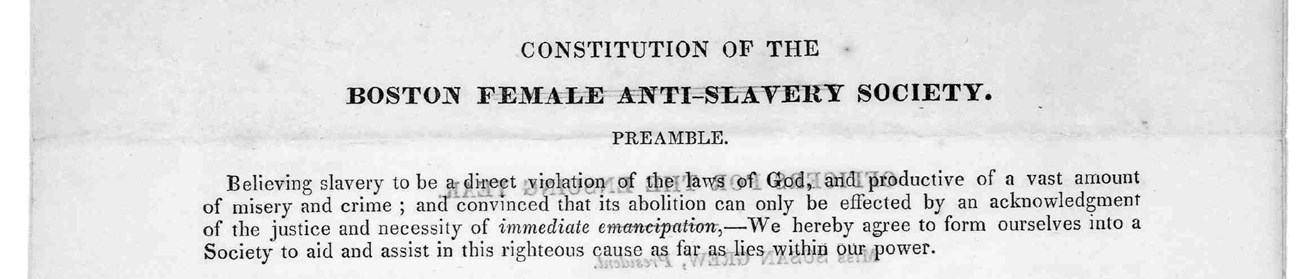

Founded in 1833 by twelve women, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society stated in its constitution:

Believing slavery to be a direct violation of the laws of God, and productive of a vast amount of misery and crime; and convinced that its abolition can only be effected by an acknowledgement of the justice and necessity of immediate emancipation, - We hereby agree to form ourselves into a Society to aid and assist in this righteous cause as far as lies within our power.[5]

Library of Congress

Its members came from a cross section of Boston society. This group included wealthy, middle, and working class Black and White women, many of whom had different religious backgrounds. Influential intellectuals and writers such as Maria Weston Chapman and Lydia Maria Child served in the organization. Others worked as teachers, seamstresses, and domestic servants. Many had marital and familial ties to prominent male activists such as Louisa Nell, Helen Garrison, and Susan Paul.[6] Charlotte Phelps served as the organization’s first president.[7]

Activism

In its constitution, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society stated that its "funds shall be appropriated to the dissemination of TRUTH on the subject of Slavery, and the improvement of the moral and intellectual character of the colored population."[8] In keeping with this charge, the organization hosted and attended lectures, started a primary school for Black girls, and organized the Samaritan Asylum for orphaned Black children.

Additionally, in 1835, the group circulated 2000 pamphlets across the region that promoted the abolitionist cause and encouraged women to either join the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society or create their own local anti-slavery groups.[9] A couple years later in 1837, the society helped organize the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, held in New York City. They also sponsored and promoted a lecture tour of Angelina and Sarah Grimke.

National Archives Documents of the 24th Congress

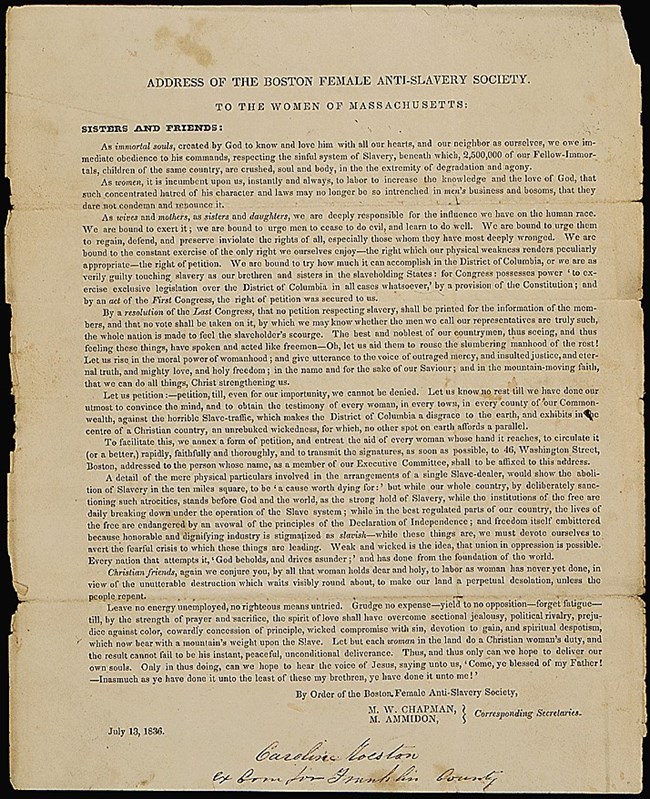

The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society spearheaded several multistate abolitionist petition campaigns. Members canvassed the region and established networks to garner significant amounts of signatures to send to Congress. For example, in one petition seeking to abolishing the slave-trade in Washington, D.C., the group wrote:

Let us know no rest till we have done our utmost to convince the mind, and to obtain the testimony of every woman, in every town, in every county of our Commonwealth, against the horrible Slave-traffic, which makes the District of Columbia a disgrace to the earth, and exhibits in the centre of a Christian country, an unrebuked wickedness, for which , no other spot on earth affords a parallel.[10]

In addition to the petition drives, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society organized the annual Anti-Slavery Fairs. These well-attended bazaars occurred around the holidays and featured a wide variety of goods for sale. Among other items, people could purchase The Liberty Bell, an abolitionist and literary gift book that accompanied each fair. Collectively, the Anti-Slavery Fairs hosted by the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society over the years raised $65,000. These funds helped sustained male abolition societies, sponsored lectures, and supported the publication and dissemination of various abolition tracts.[11]

Funds raised also allowed them to hire legal counsel to successfully sue for the freedom of Med, an enslaved child brought to Boston by her enslaver. This case, Commonwealth v. Aves, led to Med’s immediate freedom and the ruling by the state’s highest court that enslaved people voluntarily brought to Massachusetts could not be held against their will.[12]

Dissolution

By 1840, however, the original Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society disbanded "amid confusion, acrimony, and a bitterness that lasted for decades."[13] Internal schisms arose over differing visions of the goals and methods of the movement. These contentious debates included the role of clergy, women’s rights, as well as the use of political action.[14]

Despite its relatively short existence of seven years, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society achieved a great deal of tangible results through its petition campaigns, fairs, publications, lectures, and other activist work. Furthermore, the actions of the members of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, and similar female organizations:

were a foundational experience for many women’s rights activists, who received their first political education in networking, canvassing, mobilizing, and movement formation in abolition.[15]

Indeed, many continued their work in the anti-slavery movement and lent their powerful voices to the Women’s Suffrage movement in the years and decades to come.

Footnotes

[1] The Boston Mob of “Gentlemen of Property and Standing”: Proceedings of the Anti-slavery Meeting Held in Stacy Hall, Boston, on the Twentieth Anniversary of the Mob of October 21, 1835, (Boston: R.F. Walcutt, 1855), 24.

[2] Debra Gold Hansen, “The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and the Limits of Gender Politics,” The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994), 50.

[3] Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998), 203.

[4] Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Right and Wrong in Boston, (Boston: Issac Knapp, 1836), 34-37 Right and Wrong in Boston : Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

[5] Constitution of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (April, 1834). Constitution of the Boston Female anti-slavery society. [1834]. | Library of Congress (loc.gov)

[6] Louisa Nell, wife of William G. Nell, a founding member of the Massachusetts General Colored Association, and mother to activist and historian William Cooper Nell, Helen Garrison, wife of William Lloyd Garrison, and Susan Paul, daughter of Rev. Thomas Paul, activist and longtime minister of the African Meeting House

[7] Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 272, Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in the White Republic, 1829-1889, (New York: Penguin, 2012), 56, James O. Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1979), 69, Charlotte Phelps married abolitionist minister Amos Phelps..

[8] Constitution of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (April, 1834).

[9] Megan Irene Brady, "The Charge of Deserting Their Sphere: The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and Women’s Place in the Abolitionist Movement" (2018). Graduate Masters Theses. 535. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses/535, 19-20

[10] U.S. House of Representatives, "Address of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society", National Archives Catalog, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/306639

[11] Stephen Kantrowitz, 56, Julie Roy Jeffrey, The Great Silent Army of Abolitionism: Ordinary Women in the Antislavery Movement. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 108.

[12] Hansen, in The Abolitionist Sisterhood, 50.

[13] Hansen, in The Abolitionist Sisterhood, 45-46.

[14] For a more in-depth look at the dissolution of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, see Julie Roy Jeffrey, “The Liberty Women of Boston: Evangelicalism and Antislavery,” The New England Quarterly, March 2012, Vol. 85, No. 1 (March 2012), pp. 38-77, and Debra Gold Hansen, Strained Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993).

[15] Sinha, 278.