Part of a series of articles titled Superintendent Articles about Brown v. Board of Education NHP.

Article

The Brown v. Board of Education Decision Related to Native Americans

National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the US Supreme Court

[Images of the original letters are available online starting at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/278083485?objectPage=533.]

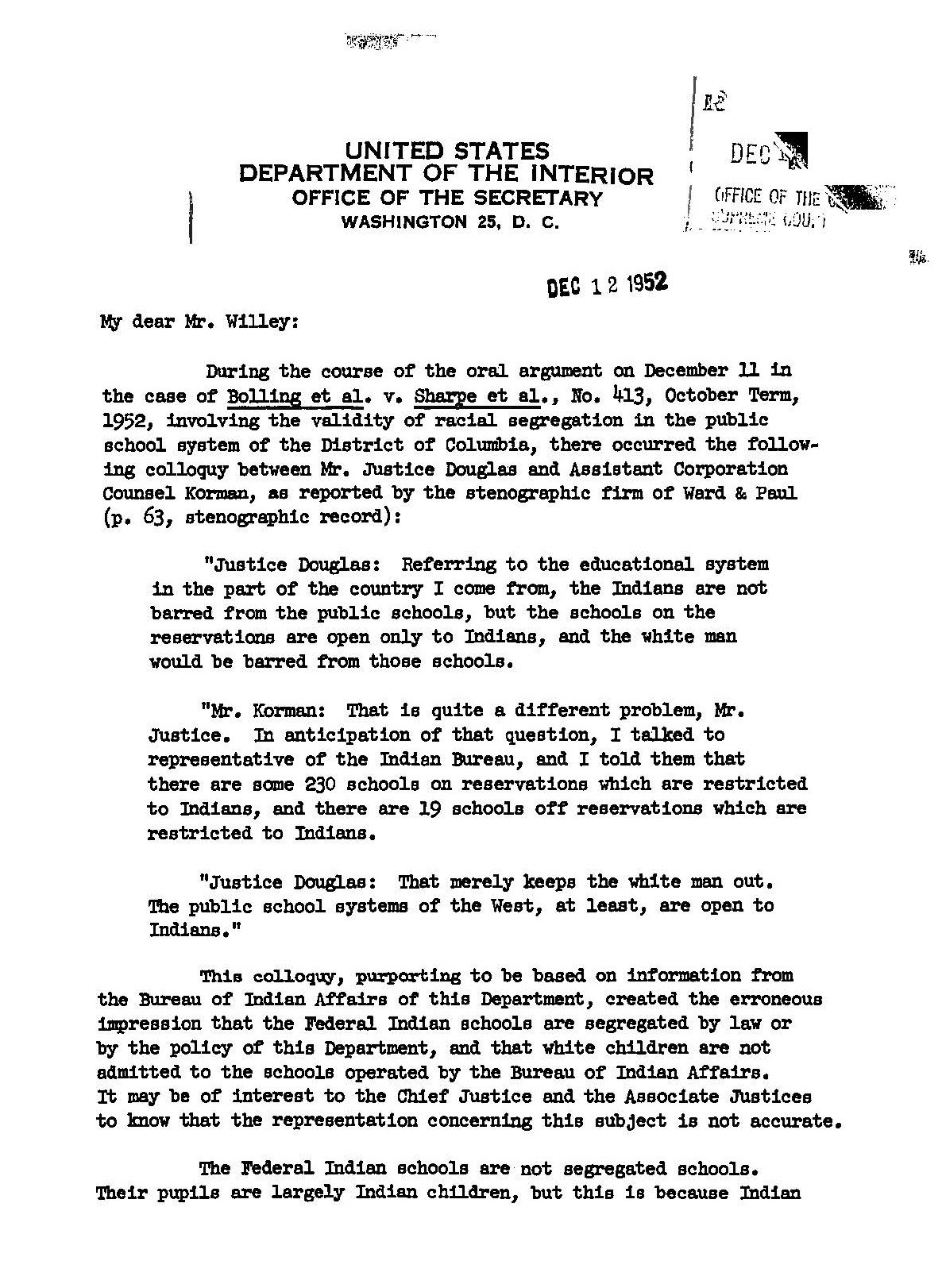

Transcript: Letter from Oscar Chapman, Secretary of the Interior, to Harold B. Willey, Clerk, US Supreme Court, December 12, 1952

[Department of the Interior letterhead]United States Department of the Interior

Office of the Secretary

Washington 25, D.C.

Dec 12 1952

My dear Mr. Willey:

During the course of the oral argument on December 11 in the case of Bolling et al. v. Sharpe et al., No. 413, October Term, 1952, involving the validity of racial segregation in the public school system of the District of Columbia, there occurred the following colloquy between Mr. Justice Douglas and Assistant Corporation Counsel Korman, as reported by the stenographic firm of Ward & Paul (p. 63, stenographic record):

“Justice Douglas: Referring to the educational system in the part of the country I come from, the Indians are not barred from the public schools, but the schools on the reservations are open only to Indians, and the white man would be barred from those schools.

"Mr. Korman: That is quite a different problem, Mr. Justice. In anticipation of that question, I talked to representative of the Indian Bureau, and I told them that there are some 230 schools on reservations which are restricted to Indians, and there are 19 schools off reservations which are restricted to Indians.

"Justice Douglas: That merely keeps the white man out. The public school systems of the West, at least, are open to Indians.”

This colloquy, purporting to be based on information from the Bureau of Indian Affairs of this Department, created the erroneous impression that the Federal Indian schools are segregated by law or by the policy of this Department, and that white children are not admitted to the schools operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. It may be of interest to the Chief Justice and the Associate Justices to know that the representation concerning this subject is not accurate.

The Federal Indian schools are not segregated schools. Their pupils are largely Indian children, but this is because Indian

[page 2] schools are generally located in isolated Indian country where most of the children of school age are Indians, or because, in the case of the few Indian schools that are located in populous areas, the non-Indian children in the vicinity usually have access to other educational facilities which their parents regard as preferable. Any white or other non-Indian children in the area of an Indian school may obtain admission to it. During the school year 1951-1952, there were 247 non-Indian children enrolled in the Federal Indian schools.

Perhaps it should also be mentioned that where State public schools are available for Indian children, it is the policy of the Department of the Interior to have the Indian children go to those public schools.

Ten copies of this letter are enclosed, for your convenience. I am also sending a copy of this letter to the Corporation Counsel for the District of Columbia.

Sincerely yours,

[signature of Oscar L. Chapman]

Secretary of the Interior

[addressed to:]

Hon. Harold B. Willey

The Clerk

National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the US Supreme Court

Transcript: Letter to Harold B. Willey, Clerk, US Supreme Court, from Milton D. Korman, Assistant Corporation Counsel, District of Columbia, December 16, 1952

[District of Columbia letterhead]Government of the District of Columbia

Office of the Corporation Counsel

District Building

Washington 4, D. C.December 16, 1952.

[addressed to:]

Hon. Harold B. Willey,

Clerk, Supreme Court of the United States,

Washington, D. C.

Dear Mr. Willey:

I am today in receipt of a copy of a letter dated December 12, 1952 addressed to you by Hon. Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary of the Interior of the United States. In that letter Mr. Chapman infers that during oral argument on December 11th in the case of Bolling v. Sharpe, No. 413, I gave to the Court inaccurate information. If there was any inaccuracy in the facts that I gave to the Court, it resulted directly from having so received the facts in the course of telephone conversations had with representatives of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior. It may also be noted in passing that the quotation contained in Mr. Chapman’s letter shows that Mr. Justice Douglas was of the same impression as I because he is quoted as saying:

So that it may not be thought that I have intentionally misrepresented a fact to the Court, I should like to point out that I advised the Court that facts concerning the Indian schools were obtained in a conversation had by me with a representative of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. I detail the following from contemporaneously made pencil notes of the telephone inquiry, which, fortunately, I was able to locate.

My first call to the Interior Department was to Mr. William H. Flanery on Extension 601. Mr. Flanery is Assistant Solicitor of the Department of Interior in Charge of Indian Affairs. After general conversation with him concerning the status of the Indian as to citizenship and concerning laws governing the sale of liquor to Indians, I inquired specifically about Indian schools and was referred by Mr. Flanery to a Miss Gifford, who, I was told, is Assistant Chief of the Education Division in the Indian Bureau, and whose telephone extension was given as 4323.

Since receipt of Mr. Chapman’s letter, which contains the statement that during the school year 1951-1952 there were 247 non-Indian children enrolled in the Federal Indian schools, I made further inquiry by having an associate, Lyman J. Umstead, Esq., call at the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Mr. Umstead talked with a Mr. P. W. Danielson in Room 4106, Department of Interior Building. Mr. Danielson, I am informed, is in the Education Branch of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He advised Mr. Umstead that the 247 non-Indian children referred to by Mr. Chapman as being enrolled in Federal Indian schools are all enrolled in 19 of the 230 Federal Indian schools which are located on Indian reservations. Upon inquiry by Mr. Umstead concerning whether there were any non-Indians enrolled in schools off Indian reservations, he was advised by Mr. Danielson that the 247 non-Indians enrolled during the 1951-1952 school year were all enrolled in schools located on Indian Reservations, and that they pay tuition while the Indians do not. It may well be that, at the time of my inquiry of her, Mrs. Thompson forgot about this small number of non-Indians.

I recall further that I asked Mrs. Thompson for references to Acts of Congress establishing the various Indian schools and was told to inquire of the legal division. Another call to Mr. Flanery elicited the reply that I would have to look back through all the annual appropriation acts for such information. Time did not permit such an exhaustive search.

I repeat that if any erroneous impression was given the Court it resulted from misinformation from the Department of the Interior. After

[page 3] twenty-seven years of building a reputation before all the courts of the District of Columbia, I would hardly start deceptions in the Supreme Court of the United States.

Very truly yours,

[signature of Milton D. Korman]

Milton D. Korman

Assistant Corporation Counsel, D. C.

MDK: ehh

cc Secretary of the Interior

Library of Congress (neg. no. LC-USZ62-38828)

The Justices' Exchange with Korman about Native Americans

This exchange illustrates an issue that came up in the arguments about school segregation at the time. In this instance, the place of Indian schools remained a tangent to the main legal arguments about separation of Whites and Blacks in schools. Milton D. Korman, a lawyer for the District of Columbia, argued to the court that D.C. school segregation was justified. He was interested in defending the accuracy of facts provided by the Department of the Interior that he had used in oral arguments. It was about his reputation before the court.

However, there was more to the issue than was quoted by Secretary Chapman. The question posed by Justice Robert H. Jackson came after Korman’s lengthy argument about the applicability of the Fifth Amendment in the case of Bolling v. Sharpe, rather than the Fourteenth Amendment that plaintiffs were arguing in the other cases provided equal protection to Black students. Korman stated:

“The Fifth Amendment contains a due process clause, as does the Fourteenth Amendment. It does not, however, contain an equal protection clause. It has been said by this Court that the Congress is not bound not to pass discriminatory laws. It can pass discriminatory laws, because there is no equal protection clause in the Fifth Amendment. This Court has likewise over a long period of time, some ninety years, said that under the Fourteenth Amendment separate schools for white and colored children may be retained.” [Leon Friedman, ed., Argument: The Oral Argument before the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 1952-55 (New York, 1969), 134]

The D.C. case was different than the other four. The court issued a separate opinion on the same day as the other Brown cases on May 17, 1954. The logic was essentially the same, but because the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply specifically to the District of Columbia, the court had to resolve the question—and overturn the precedents Korman cited in 1952—of whether the Fifth Amendment, which did apply to Congressional action in governing the District of Columbia, prohibited racial segregation.

So this is how the subject of federal schools for Native American children entered the picture. This is the full exchange between Korman and the justices regarding Native Americans:

[Korman:] Before I leave the Fifth Amendment, there was a suggestion by Mr. Justice Jackson that there might be effect upon the Indians if this Court should hold that separate schools may not be maintained under the Fifth Amendment. And I suggest that there are whole chapters of the United States Code which are entitled ‘Protection of the Indians,’ and under which Congress has legislated especially for them, because it is recognized that there is a people that needs protection. You and I can go out and buy a bottle of liquor if we want. The Indian cannot, nowhere in the United States. And he is a citizen. Why? Because it is recognized that it is not good for him, and he needs protection.

That assumes, I know, that it is good for us.

JUSTICE JACKSON: I live very close to the Seneca Reservation, in New York, and I would just as soon deal with a drunken Indian as with a drunken white man, myself, under modern conditions. It may have been different in the days of scalping knives.

MR. KORMAN: Possibly so.

Library of Congress, neg. no. LC-USZ62-44543

JUSTICE [WILLIAM O.] DOUGLAS: Referring to the educational system in the part of the country I come from, the Indians are not barred from the public schools, but the schools on the reservations are open only to Indians, and the white man would be barred from those schools.

MR. KORMAN: That is quite a different problem, Mr. Justice. In anticipation of that question, I talked to representative of the Indian Bureau, and I was told by them that there are some 230 schools on reservations which are restricted to Indians, and there are nineteen schools off reservations which are restricted to Indians.

JUSTICE DOUGLAS: That merely keeps the white man out. The public school systems of the West, at least, are open to Indians.

MR. KORMAN: That may be. But that is a state proposition, left up to the states in the individual case. If the states want to let them in and think that it will not cause a problem, that is up to the legislation of the states.

JUSTICE DOUGLAS: Some of these cases are state questions.

MR. KORMAN: Perhaps.

JUSTICE DOUGLAS: Not yours?

MR. KORMAN: Perhaps. I call your attention to the fact that there is separation, I have learned, by sexes in many of the large cities of the country, not in all the schools, apparently, but in some, perhaps for some special reason. I find from the National Education Association that they have separate schools for the sexes in San Francisco, Louisville, New Orleans, Baltimore, Boston, Elizabeth, Buffalo, New York City, even, Cleveland, Portland, Philadelphia. Such cities as those separate by sexes. Those are the things which are left to the decision of the decision of the legislature, the competent authority in each case to decide what is best for that community. [Friedman, ed., Argument, 136-137]

This exchange in 1952 foreshadowed the ripple effect that the court’s Brown decision would have in American education. In other words, if racial segregation between Blacks and Whites was unconstitutional, what about other racial and ethnic groups? Would the court have something to say about educational segregation by sex or gender? Whether he knew it or not, in arguing for the states and District of Columbia to remain in charge of these decisions, Korman represented the last gasps of the states’ rights theory of educational control. Korman laid out the argument that the courts should let society evolve at its own pace; progress is happening, so let it happen without interference. He concluded his oral argument this way:

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, Washingtoniana Division

This is not generally known, but in the southwest section [of D.C.] there have been joint meetings called of teachers, parents and pupils where they confer together for the betterment of their neighborhood. Those are steps which have been accomplished without the intervention of courts, without the intervention of legislative bodies, and if those things have been accomplished, pray God the day will come when all things will be merged and the white and colored men will meet together in every place, even in the school, and it will not require even arguments from my friends before the halls of Congress, because there will be a general acceptance of the proposition that these two races can live side by side without friction, without hostility, without any occurrences.

If that be so, then there will be a general movement without their taking any action to help it, without their seeking it, to bring those things about. . . .

That is what I urge upon this Court, to leave this issue where constitutionally it belongs, in the body that can legislate one way or another as it finds the situation to be and as it finds the needs to be in each community. Particularly I speak for the District of Columbia. But I say it is true in all areas. And these allusions to the Japanese cases and the other cases that they have said to Your Honors control this situation, I say they do not. In those cases, there were complete denials. Hirabayshi, Korematsu, and Endo were kept in their homes as prisoners. They were taken from their homes and put in concentration camps. Takahashi was denied the right to fish, and in the Farrington case, which they say is the nearest approach to their problem, there was an attempt to legislate out of existence by regulation the foreign language schools in Hawaii.

In each of these cases, there was either denial or an attempt to completely deny. These people [in the current case in D.C.] are denied nothing. They have a complete system of education, which they admit is equal in all respects. They do not raise that issue.

I say to the Court that this issue should be left to the Congress where it belongs. There is no constitutional issue here. It has been decided by this Court. It should be left where it is now. [Friedman, ed., Argument, 140-141]

* * * * *

This issue of Native American schools had actually arisen two days before when the court heard oral arguments in the Briggs v. Elliott case from Summerton, South Carolina. This time, Justice Jackson asked Thurgood Marshall, NAACP attorney for the plaintiffs, if the Fourteenth Amendment was relevant to Indian schools.

JUSTICE JACKSON: Coming back to the question that Justice Black asked you, could I ask you what, if any, effect does your argument have on the Indian policy, the segregation of the Indians. How do you deal with that?

MR. MARSHALL: I think that again that we are in a position of having grown up. Indians are no longer wards of the Government. I do not think that they stand in any special category. And in all the southern states that I know of, the Indians are in a preferred position so far as Negroes are concerned, and I do not know of any place where they are excluded.

JUSTICE JACKSON: In some respects, in taxes, at least, I wish I could claim to have a little Indian blood.

MR. MARSHALL: But the only time it ever came up was in the—

JUSTICE JACKSON: But on the historical argument, the philosophy of the Fourteenth Amendment which you contended for does not seem to have been applied by the people who adopted the Fourteenth Amendment, at least in the Indian case.

MR. MARSHALL: I think, sir, that if we go back even as far as Slaughter-House and come up through Strauder, where the Fourteenth Amendment was passed for the specific purpose of raising the newly freed slaves up, et cetera, I do not know.

JUSTICE JACKSON: Do you think that might not apply to the Indians?

MR. MARSHALL: I think it would. But I think that the biggest trouble with the Indians is that they just have not had the judgment or the wherewithal to bring lawsuits.

JUSTICE JACKSON: Maybe you should bring some up.

MR. MARSHALL: I have a full load now, Mr. Justice. [Friedman, ed., Argument, 50-51]

- Even well-educated Supreme Court justices could hold stereotypical views of Native Americans and not be embarrassed to use those views in exchanges with attorneys before the court.

- Some Americans anticipated the logical extension of desegregation to other excluded groups should the court decide that segregation of Blacks in schools was unconstitutional.

- There was no united “civil rights movement” yet. It would be well into the 1960s and 1970s before other groups had their day in court and achieved legal victories toward equality.

“The road taken by the Supreme Court in getting to Brown did not pass through Indian country,” Baca asserts. [1168] The eventual consideration of Indian education came to the Supreme Court in 1994, with roots in a case filed in 1973 as Sinajini v. Board of Education. In that case, the Native American Rights Fund sued “to bring elementary and secondary schools to the Utah portion of the Navajo Indian Reservation.” By 1994, sixty-six high school students in Utah asked the school district in which they lived to build a high school so that students did not have to attend federal boarding schools in Arizona, ninety miles away from their Navajo Mountain community. When the San Juan County school district refused, the Meyers case was filed. [1171]

As Baca argues, “The question before the court was a simple one: Who had the legal duty to provide elementary and secondary educational services to American Indian children who lived within the external boundaries of an Indian reservation?” [1171] The United States agreed with the Navajo plaintiffs that the state and county had the duty to education American Indian children. Utah asserted that the duty should be shared by the federal, state, and county governments. The school district wanted the federal government to assume all responsibility for Indian education. The Supreme Court essentially concluded that Utah’s argument was closest to the law. “The court concludes that all of the entities involved in this case—the District, the State, the United States and the Navajo Nation—each has a duty to educate the children of Navajo Mountain. The duty of one does not relieve any other of its own obligation,” the majority wrote. Using a combination of federal and state funds, the school district built a high school at Navajo Mountain. [1180]

San Juan School District (https://www.sjsd.org/o/nmhs; accessed 6/10/2024)

Article author: James H. Williams, PhD, Superintendent

Last updated: June 10, 2024