Last updated: April 4, 2023

Article

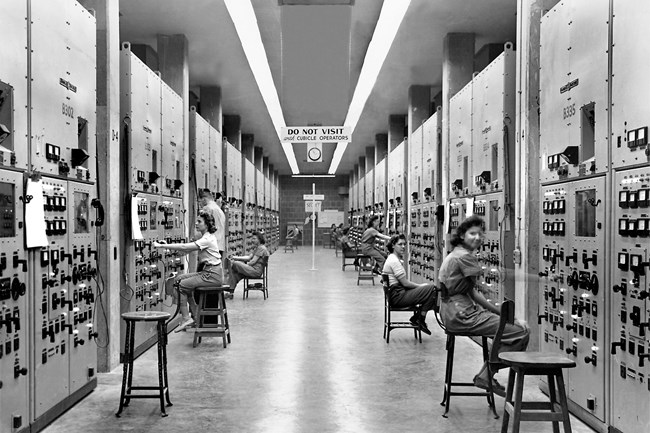

The Calutron Girls

US DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY/ED WESTCOTT

During the Manhattan Project, approximately 10,000 young women operated the arrays, or racetracks, at Oak Ridge's Y-12 Electromagnetic Isotope Separation Plant. Beginning in 1944, when the first arrays went online, these women, known as Calutron Girls, began separating lighter uranium 235 from the heavier and more common uranium 238. This separated uranium 235 ultimately became fuel for Little Boy, the atomic bomb designed and built in Los Alamos and dropped on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945.

To maintain secrecy in a community with over 75,000 workers and residents, Manhattan Project administrators did not offer these 10,000 young women any clue of what they were working on. Several of these women recalled instances of coworkers disappearing from their jobs unexpectedly, often because they had been too inquisitive about their work.

As a whole, the Calutron Girls operated the dials at Y-12 more efficiently than scientists. Being unaware of the intricacies of their work, the women were more likely to simply notify their supervisors of a problem rather than try to correct it themselves as a scientist would. In addition, their touch on the dials proved to be more efficient than scientists who would overthink the adjustments.

The 1,152 calutrons at Y-12 operated by the Calutron Girls produced 140 pounds of uranium 235 through 1944 and 1945, enough to fuel one atomic bomb. On August 6, 1945, these women finally learned what they had been so diligently working on, the fuel for the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan.

Ruth Hiddleston, a Calutron Girl, recalled her feelings after learning of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima: "I was at work and they announced it, you know. At first you were glad to think the war was over. The first thing I thought was 'my boyfriend will be home.' Then I got to thinking, they start telling all the people that were killed over there. It made you think of something else, that I had a part in it, because that’s what they told us. They said it’s been dropped there, and then they said so many thousands or a million or whatever—I don’t remember. Anyway, I didn’t much like that idea that I had a part in it. But you know, war is war. Ain’t nothing you can do about it but try to stop it. I still don’t like the idea, you know. But you’ve got to do it. Somebody does."

Listen to Ruth Hiddleston's full interview at the Atomic Heritage Foundation's Voices of the Manhattan Project.

- Johnson, Charles W., and Charles O. Jackson. City Behind a Fence: Oak Ridge, Tennessee 1942-1946. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

- Department of Energy. "Five Fast Facts About the 'Calutron Girls'." Department of Energy, April 5, 2018. Five Fast Facts About the "Calutron Girls" | Department of Energy

- Oak Ridger. "Atomic Bombs dropped 75 years ago: A 'Calutron Girl' remembers." Oak Ridger, June 15, 2020. Atomic bombs dropped 75 years ago: A 'Calutron Girl' remembers (oakridger.com)

- Atomic Heritage Foundation. "Voices of the Manhattan Project: Ruth Huddleston's Interview." Ruth Huddleston's Interview - Nuclear Museum