Last updated: January 22, 2021

Article

The “Fine Times” of James A. Garfield’s Education, Part II

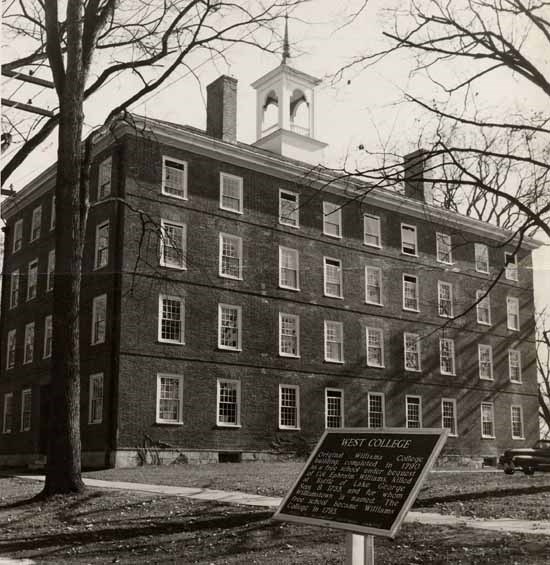

To obtain an actual degree, Garfield’s first inclination was to attend Bethany College because of its affiliation with the Disciples of Christ. However, in the spirit of opening up his mind to new ideas he settled on Williams College in Massachusetts and moved there with his Hiram friend and former teacher Charles Wilber in the summer of 1854. Williams was nonsectarian but still strongly religious, like the Eclectic. But unlike Hiram, religious sentiment was more Calvinist, and the New England atmosphere seemed exotic compared to Garfield’s rustic life in Ohio. Despite his cultural differences, though, he eventually won the acceptance of his New England classmates, who gave him the nickname “Gar”. His education at the Eclectic qualified him as a junior at Williams and he once again buried himself in his studies.

It was there, at Williams, that Garfield finally found an appropriate academic niche for his abilities: he performed well and would receive some accolades for his achievements, but he never outpaced the other students like he had in Chester or Hiram. Allan Peskin writes in his authoritative biography Garfield: “Students and teachers alike regarded him as a good, but not brilliant student, who stood well in the upper half of his class, but never seriously challenged his better-trained colleagues.” Just reading his comparatively sparse journal entries during his time in Massachusetts gives one the feeling that Garfield was too focused on his studies to write regularly. But none of this is meant to imply that Garfield performed poorly – in fact, he learned and accomplished much at Williams. He was considered by some classmates as one of the most capable debaters the college had ever seen; he was elected president of one of the main literary societies at the school; he even found himself chosen as the editor of a college publication, the Williams Quarterly. His knack for languages expanded to include German and Hebrew, and he came to enjoy studying the natural sciences even more. At Williams, Garfield discovered that he not only had a natural ability to learn easily, but that he also had the drive and work ethic to match it when that natural ability by itself was not enough to keep up with his peers.

Library of Congress

In later years Garfield would recall the exact beginning of his intellectual life: witnessing an address in Williamstown by the essayist and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. Arguably, though, his intellectual calling had begun earlier when he found that he loved being a student. He would return to Hiram in 1856 as a full-time teacher and then school president the following year. But his academic side carried on beyond that role as well and would influence virtually every aspect of his life and career. During the Civil War, Garfield had no official military training but recognized his own strength as a quick learner, so he read biographies on Napoleon and studied every book on military tactics he could find. As Chief of Staff of the Army of the Cumberland he spurred the West Point-trained General Rosecrans to action before the Tullahoma Campaign with a lengthy, essay-like report that logically listed point-by-point every reason the army should attack the enemy.

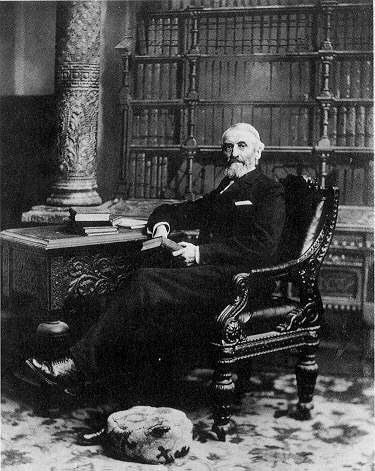

In Congress, he was a firm ally of education, saying in a speech in 1879: “If… we allow our youth to grow up in ignorance, this Republic will end in disastrous failure.” He proposed the bill for the creation of the federal Department of Education (which passed and formed in 1867), supported the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute after the Civil War for the education of blacks, was a regular visitor to the Library of Congress, and introduced a bill to provide military education in colleges (a forerunner to ROTC, which ultimately did not receive enough interest to pass). Ainsworth Spofford, the head of the Library of Congress for over 30 years, recalled Garfield being one of the most frequent users of the collection there. It was also in Congress that Garfield developed a unique proof of the Pythagorean theorem still used by some today.

National Park Service

Learning was a big part of Garfield family life. Academics and books gave James and Lucretia an additional common bond early on in their courtship, and she would continue to be an intellectual counterpart to her husband throughout their marriage. Naturally he took a scientific approach to farming in Mentor – his diaries mention different experiments with soil, crops, and irrigation. He was also very interested in the progress of his children’s education. He was confused why his oldest sons did not share the same love of education that he had, noting in his diary that “the mind naturally hungers and thirsts for knowledge.” Before their move to the Mentor home, he had decided to send Harry and Jim to a private school, believing the public schools to be too crowded and the students overworked; Mollie would stay home to learn “something of books” and housekeeping. In December 1874, he wrote happily in his diary “Harry and Jimmy have this Winter awaked to the love of reading.” Garfield continued to help with their studies and all five of his children who lived to adulthood had very successful lives of their own.

The Mentor house itself stands as proof of the President’s love for reading and learning. Nearly every room of the house has at least a few books in it, and this seems pretty exact to how it appeared when Garfield lived there as well. A reporter wrote that “His real pleasure seems to be when poring over his books.” Another visitor to the house in the late 1870s wrote:

“..you can go nowhere in the general’s home without coming face to face with books. They confront you in the hall when you enter, in the parlor and the sitting room, in the dining-room, and even in the bath-room, where documents and speeches are corded up like firewood.”

Even his Inaugural Address discussed the importance of education in a government that derives its power from its citizens. Garfield started to prepare his speech by studying the Inaugural Addresses of his predecessors. In his own Address, he pointed out the alarming percentage of illiteracy indicated by the recent census and announced what he believed to be the cure: “For the North and South alike there is but one remedy. All the constitutional power of the nation and of the States and all the volunteer forces of the people should be surrendered to meet this danger by the savory influence of universal education.” Stating that their children will one day be the inheritors of their government, he added “It is the high privilege and sacred duty of those now living to educate their successors and fit them, by intelligence and virtue, for the inheritance which awaits them. In this beneficent work sections and races should be forgotten and partisanship should be unknown.” For Garfield, education and intelligence were not just ways of allowing one individual to “rise above the herd” – education for everyone, regardless of race or class, provided the surest foundation for the perpetuation of the nation itself. Learning offered the means for which Garfield was able to live a successful life, and it is little surprise that he believed that to be the surest way for others as well.

Due to his assassination, we will never know where his scholastic calling would have called him next, or if he would have been successful in his plans for the Presidency. But his statements during his Inauguration as President of the United States act as an appropriate summation of how academics and education had influenced Garfield’s own life. Perhaps most fitting of all, later that evening the Inaugural Ball was held not in a temporary structure as many balls before, but in the new Smithsonian Museum.

Written by T.J. Todd, Former Visitor Use Assistant, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, March 2013 for the Garfield Observer.

(Thanks to Jennifer Morrow of the Hiram College Archives for her generous assistance.)