Last updated: September 18, 2024

Article

The Pulitzer Trophy and National Air Races at Wilbur Wright Field

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

[1] Gough, 134.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Image courtesy of the United States Air Force.

Sources for further information:

“The Air Races.” Dayton Daily News, 6 October 1924, p. 6

Aircraft Year Book 1925. New York, N.Y.: Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce of America, 1925. Pages 189-192 specifically address the Dayton races.

Clouse, Michael. “More Than a Road: The Story Behind Wright-Patt's Skeel Avenue.” https://www.wpafb.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/3056048/more-than-a-road-the-story-behind-wright-patts-skeel-avenue/. Accessed 28 May 2024.

“The Dayton Airplane Show.” New York Times, 6 October 1924, p. 18.

Gough, Michael. The Pulitzer Air Races: American Aviation and Speed Supremacy, 1920-1925. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2013.

Gwynn-Jones, Terry. Farther and Faster: Aviation’s Adventuring Years, 1909-1939. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991.

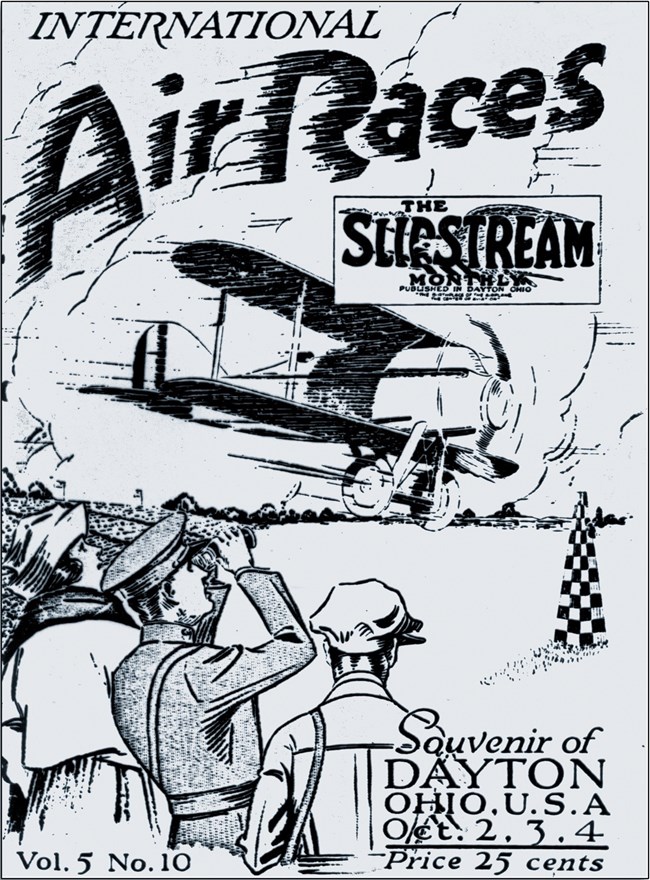

Ortensie, Ray, “Wilbur Wright Field and the 1924 International Air Races,” https://media.defense.gov/2020/Aug/06/2002472287/-1/-1/1/FLASHBACK_1924%20INTERNATIONAL%20AIR%20RACES.PDF, accessed 24 June 2024.The Slipstream Monthly. Vol. 5, no. 10 (October 1924). This particular issue of this journal was published as a souvenir program prior to the actual event and reflects the boosterism of race promoters. The November 1924 issue (vol. 5, no. 11) contains Marshall’s postmortem on the event.

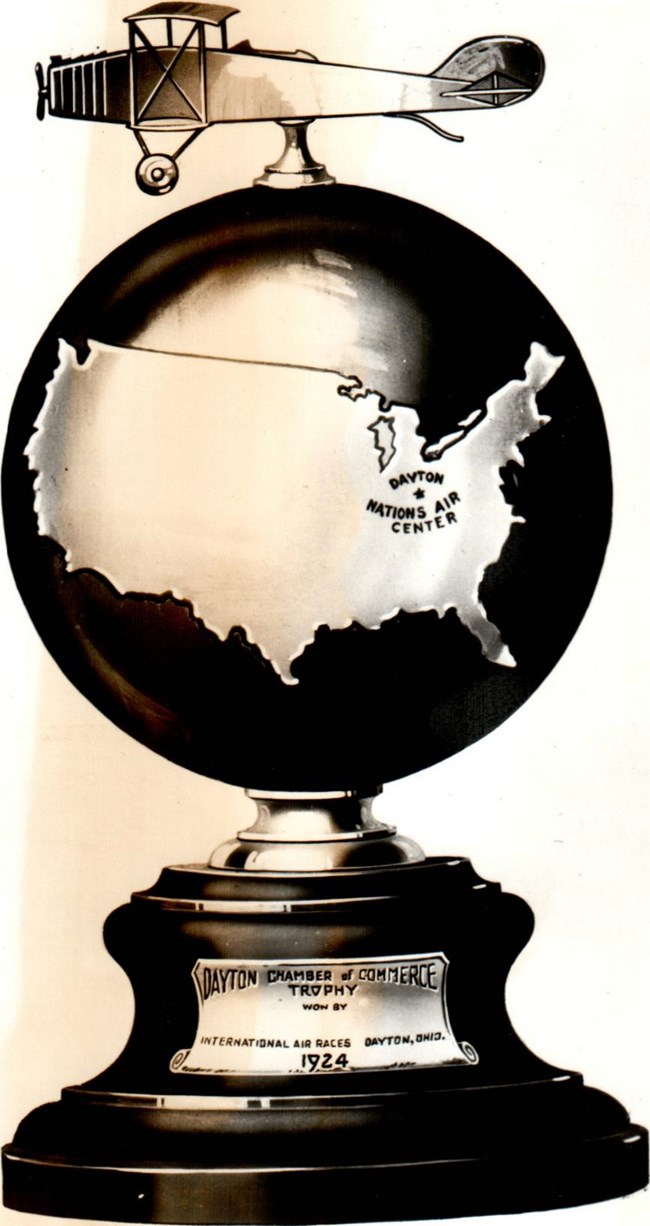

For a view of the trophy itself visit the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum page: Pulitzer Trophy.

Edward Roach June 2024

“The Air Races.” Dayton Daily News, 6 October 1924, p. 6

Aircraft Year Book 1925. New York, N.Y.: Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce of America, 1925. Pages 189-192 specifically address the Dayton races.

Clouse, Michael. “More Than a Road: The Story Behind Wright-Patt's Skeel Avenue.” https://www.wpafb.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/3056048/more-than-a-road-the-story-behind-wright-patts-skeel-avenue/. Accessed 28 May 2024.

“The Dayton Airplane Show.” New York Times, 6 October 1924, p. 18.

Gough, Michael. The Pulitzer Air Races: American Aviation and Speed Supremacy, 1920-1925. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2013.

Gwynn-Jones, Terry. Farther and Faster: Aviation’s Adventuring Years, 1909-1939. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991.

Ortensie, Ray, “Wilbur Wright Field and the 1924 International Air Races,” https://media.defense.gov/2020/Aug/06/2002472287/-1/-1/1/FLASHBACK_1924%20INTERNATIONAL%20AIR%20RACES.PDF, accessed 24 June 2024.The Slipstream Monthly. Vol. 5, no. 10 (October 1924). This particular issue of this journal was published as a souvenir program prior to the actual event and reflects the boosterism of race promoters. The November 1924 issue (vol. 5, no. 11) contains Marshall’s postmortem on the event.

For a view of the trophy itself visit the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum page: Pulitzer Trophy.

Edward Roach June 2024

Tags

- dayton aviation heritage national historical park

- wright brothers national memorial

- wright brothers

- dayton aviation heritage national historical park

- wright brothers national monument

- huffman prairie flying field

- historic aviation locations

- aviation

- discover aviation

- wright brothers national memorial

- birthplace of aviation