Part of a series of articles titled The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963.

Article

Chapter 10: Tangled Up in God's Beard

Ohio Department of Highways, Short Course on Roadside Development, Vol. 18 (Columbus: Ohio Department of Highways, 1959): 93.

The Watsons stop at a rest area just outside of Toledo, Ohio, for a bathroom break and sandwiches with grape Kool-Aid.

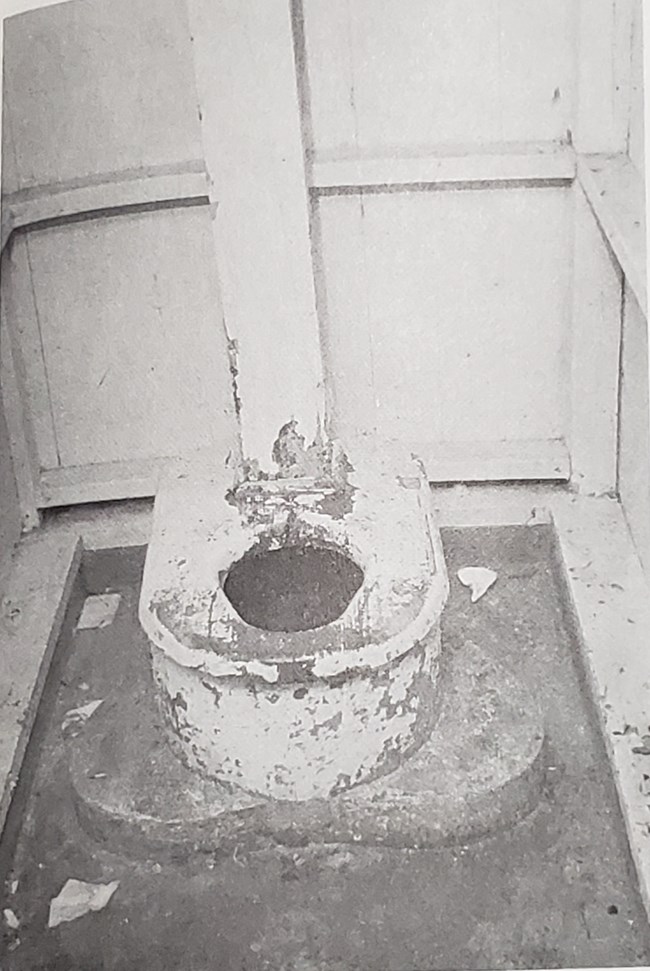

The place looks like a log cabin, which Kenny thinks is really cool, until he discovers that the bathroom is just an outhouse. There are no flush toilets! Kenny is grossed out by the smell and decides to relieve himself in the woods instead. After Byron complains about the toilets, Momma and Dad laugh and say he better get used to them because Grandma Sands has an outhouse, too.

Returning to I-75, the Brown Bomber lulls the Watson children in and out of sleep, with Joey occasionally drooling on Kenny's pants. Kenny removes Joey's shoes; on the inside, he notices a picture of a white boy and a smiling dog, encircled by the words "Buster Brown."

As they approach Cincinnati, Momma and Dad discuss stopping for the night, as planned. But Kenny knows his dad has secretly decided to drive straight to Birmingham without stopping to sleep. Kenny dozes through most of Kentucky and doesn't wake up until they're outside a rest area in the Appalachian Mountains of Tennessee. Unlike the Ohio rest stops, this one doesn't have bathrooms, just a picnic table and a hand pump for running water. It is so dark the Watsons can barely see. Momma doesn't feel safe stopping there at night, and the shadowy large hills and high altitude spook the children. As they go to the bathroom in the woods, Byron warns Kenny that the "redneck" locals have never seen Black people and would hang and eat them if caught. Frightened, both boys scramble back to the car. The Watsons feel safer once they are back on the highway. Dad has everyone roll down their windows and feel the cool air on their fingers. Kenny’s favorite song, "Yakety Yak," plays on the Ultra-Glide.

Momma is upset when Dad decides to drive through the night. Later, the Watsons feel anxious when they pull off at the rest area.

Image courtesy of the Tubman African American Museum, Macon, Georgia.

Fact Check: Was it dangerous for the Watsons to travel after dark?

There were many places in the United States where written codes and informal customs, combined with racist policing, made it unsafe for African Americans to travel, especially at night. The name "sundown towns" describes small towns that had only white residents by design. This fact was public: a sign might even be posted that stated exactly who was unwelcome inside its borders. Racial and ethnic minorities including African Americans, Native Americans, Chinese Americans, and Jewish Americans could not rent or buy homes in these communities. Since members of these groups couldn't live in the town or suburb, the reasoning went, they had no business being in them after dark. People deemed "undesirable" were threatened verbally and with acts of violence.

On the road, police could be another source of harassment. As is the case today, law enforcement sometimes stopped Black drivers for minor or nonexistent offenses. An African American driver could be questioned by authorities for simply owning an automobile. Black travelers had reason to fear nightfall. However, darkness also provided a cover that might let them travel through dangerous areas without being seen. Both Mr. and Mrs. Watsons' thinking made sense.

What is the evidence?

Primary source: "White men shoot up church excursioner," The Pittsburgh Courier (PA), August 17, 1940, 24.

The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the leading Black newspapers of the time, published both local stories and news of national interest to African American readers.

"Five persons returning from a church excursion at Eutawville Sunday night were wounded by shotgun blasts when they were fired upon at a filling station in Bonneau, near here [Moncks Corner, South Carolina], by unidentified white men. ...According to Rev. Mr. Mack, the bus developed motor trouble and was driven into a filling station in Bonneau and left by the driver with consent of the operator while another bus was being secured… As passengers were transferring to the second bus eight white men drove up and ordered the excursioners to 'get out here right quick. We don't allow no d—n n—rs [profanity and racial slur] 'round here after sundown.' The excursioners, the white driver and the station operator tried to explain the emergency to no avail. A second car pulled up with eight more white men who began firing on the group with shotguns. Having no weapons, the execursioners fled into nearby woods. Many were still missing when the bus left at 4:30 Monday morning."

Primary source: "Sundown sign, c. 1900." Image courtesy of the Tubman African American Museum, Macon, Georgia.

Ohio Department of Highways, Short Course on Roadside Development, Vol. 19 (Columbus: Ohio Department of Highways, 1960), 15.

Fact Check: Did rest stops in the 1960s resemble the places the Watsons stopped in Ohio and Tennessee?

What do we know?

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 provided funds for states to build safety rest areas (SRAs). The rest areas were designed to encourage people to stop since drivers who are tired are more likely to get into accidents. Safety rest areas grew out of earlier roadside parks and included basic features such as bathrooms, picnic tables, and parking lots. They did not have running water, fast food restaurants, or convenience stores that sold food and drinks. But by the late 1960s, as more Americans began using the expanding interstate highway system, rest stops offered more amenities. Even as some aspects of the roadside rest stops became standardized, however, they continued to reflect the culture and environment of the particular region in which they were built.

What is the evidence?

Primary source: Ohio Department of Highways, "Picture of an 'information station,'" Short Course on Roadside Development, Vol. 19 (Columbus: Ohio Department of Highways, 1960), 15.

Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Bud Gordon, Birmingham News.

Primary source: Bud Gordon, Birmingham News, "Ku Klux Klan sign at the city limits of Bessemer, Alabama," Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group.

This 1959 roadway "welcome" sign announces travelers' arrival in Bessemer (a suburb of Birmingham, Alabama). It is sponsored by the Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacist group. This makes the welcome ominous for Black travelers because the purpose of the KKK was preserving "white interests."

Secondary source: Mia Bay, "Traveling Black/Buying Black: Retail and Roadside Accommodations During the Segregation Era," in Race and Retail: Consumption Across the Color Line, ed. Mia Bay and Ann Fabian (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2015), 15-33.

"... black drivers learned to assemble Jim Crow kits before driving any distance. They loaded up their cars with food, water, and maps (so they would not have to stop and ask for directions) and carried amenities such as toilet paper and 'pee cans,' assuming that they would not be able to use roadside restaurants. Many also filled their gas tanks before leaving home and even carried additional gas in the trunks of their cars. If they had to stop for gas, they tried to time their trips so they could make such stops in major cities."

Ohio Department of Highways, Short Course on Roadside Development, Vol. 18 (Columbus: Ohio Department of Highways, 1960): 97.

Primary source: Ohio Department of Highways, Short Course on Roadside Development, Vol. 18 (Columbus: Ohio Department of Highways, 1960): 97.

Primary source: "More roadside rest areas needed to meet driver fatigue," Saturday Evening Post 230, no. 46 (1958): 10.

"Wilbur J. Garmhausen, chief landscape architect for the Ohio Department of Highways, reports that his department will plant some 65,000 trees this year. ...The Federal Government will help with their planting program on new Interstate Highway routes. This summer Ohio intends to add twenty-four new parks to the 269 it already has. On the Federal highways, Mr. Garmhausen says, the parks will be built at intervals of about twenty-five miles and will be laid out in pairs, one on each side of the road. Separate parking areas will be provided for automobiles and trucks, making the shaded passenger-car areas safer for children."

Secondary source: Joanna Dowling, Correspondence with the Center for Children's Books (University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign), September 3, 2021.

Dowling is a historian who studies the development of safety rest areas and the influence of highway construction during the 20th century.

"Ohio's first roadside park opened to highway motorists in 1935 ... to offer weary travelers a safe place to pull from the roadway. Located in rural areas, they ranged in size from one to two acres and accommodated about fifteen cars. A picnic table and perhaps a barbeque grille would serve as the site's functional amenities. Twenty-three years later, in 1958, Ohio opened its first interstate rest area in a rustic wood hewn scheme that ... would not only transform transportation and the American landscape, but our very way of life. Interstate rest areas offered expanded site acreage and parking and amenities that included not only picnic tables, but shelters above them, privy [outhouses] and where possible flush toilets and running water derived from onsite wells; planted grassy spaces, informational bulletin boards, shade trees and dust free walking paths."

Voices from the Field

"Traveling While Black" by Gretchen Sorin, the director of the Cooperstown Graduate Program at SUNY Oneonta and the author of Driving While Black: African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights.

Writing Prompts

Opinion

The Watsons’ “road trip food” is identified in this chapter. What is your opinion about the choices that Momma packed and how she distributed the food? Compare and contrast what the Watsons ate to what you would pack for a road trip, and why. Introduce the topic with facts and details and support your point of view with reasons and information. Provide a concluding statement related to your opinion presented.

Informative/explanatory

Find and research the details on a map showing the route I-75 clearly displayed. Identify the states that the route goes through and the number of miles it takes to get from Flint, Michigan, to Birmingham, Alabama today. Identify the cities mentioned in the chapter and identify three more cities on the route. Group the information in sections include formatting (e.g., headings), illustrations, and multimedia when useful to aid comprehension.

Narrative

Go outside when it is dark enough to see the night sky. Write a story describing what you see and the feelings the night sky evokes in you. Include at least one metaphor and one simile to better inform the reader of your personal “view” both literal and figurative, of the night sky in your neighborhood. Use concrete words and phrases and sensory details to convey experiences precisely.

Note: Wording in italics is from the Common Core Writing Standards, Grade 5. Sometimes paraphrased.

Last updated: January 5, 2024