Part of a series of articles titled The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963.

Article

Chapter 15: The World-Famous Watson Pet Hospital

A couple of weeks after the church bombing, the Watsons are back home in Flint.

Kenny overhears that the bomb killed four girls, injured many others, and was intentionally set by white men. Kenny feels safe in a special hiding spot in a small, dark area behind the sofa that Byron nicknamed the “World-Famous Watson Pet Hospital.” Kenny believes the “hospital” has magic healing powers because it is where their pets go whenever they are sick or hurt. He is hoping the magic will work on him too, although he doesn’t feel better even as he begins sleeping there.

Kenny has lost interest in his friends and toys, and Momma and Dad are worried. Byron figures out where Kenny has been disappearing, and he begins sleeping on the couch to keep Kenny company. Gradually, Byron convinces Kenny to emerge from his secret hiding place.

One day, Byron brings Kenny to the bathroom, and when Kenny looks in the mirror to check on his mustache, he starts crying and can’t seem to stop. Between sobs, he asks why people would hurt little kids. Kenny then says he's ashamed for leaving Joey to the Wool Pooh instead of fighting off the monster, like Byron did when he was in danger. Byron explains there’s no such thing as the Wool Pooh, and magic powers aren’t real either. Byron also assures Kenny that he did protect his sister.

Bryon and Kenny talk about how so many things that happened are unfair. It is unfair that the other children died even though they had families that loved them. It is unfair that grown men could hate Black people so much they’d kill Black children just to keep white and Black people separate. It is unfair that the police may know who bombed the church but won’t do anything about it. Byron says that things are never going to be fair, but they have to keep moving forward. He tells Kenny that he’s going to be alright. Kenny decides that Byron is wrong about some things and right about others. He is wrong about the Wool Pooh being made-up, and he is wrong about magic powers not being real–they exist in the loving and kind things people do for each other. But Byron was right about one thing: he is going to be alright.

Rick Bragg, “38 years later, last of suspects is convicted in church bombing: ex-Klansman gets life sentence,” New York Times (NY), May, 23, 2002, A1.

In the aftermath of the bombing, Byron asks, “How’s it fair that even though the cops down there might know who did it nothing will probably ever happen to those men?” Byron’s question was rhetorical (it did not call for an answer) because it’s obviously not fair.

Fact Check: But was he right to assume that the men would get away with it?

What do we know?

Byron doubts that the men responsible for the Sixteenth Street Church Bombing will be convicted for their crimes, and he is right to be skeptical. The bombing sparked national outrage. But there would not be a full resolution in the courts for thirty-eight years. In 1965, the FBI identified four men–Robert E. Chambliss, Bobby Frank Cherry, Thomas Edwin Blanton, and Frank Herman Cash, all members of the Birmingham chapter of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK)–as probable suspects for the bombing and murders. Despite this intelligence, the case was closed in 1968 due to claims of insufficient physical evidence and a lack of witnesses willing to testify. Alabama Attorney General Bob Baxley later reopened the case. His office’s reexamination of crucial evidence, including audio surveillance tapes, lead to new convictions. Chambliss, Blancton, and Cherry were convicted in 1977, 2001, and 2002 respectively. Cash died in 1994, before he could be sentenced.

What is the evidence?

Primary Source: Alabama, Tenth Judicial Circuit Court, State of Alabama v. Robert E. Chambliss trial transcript, 1977, State of Alabama (1977), 273-75.

Robert E. Chambliss was convicted of murder and sentenced to prison in 1977 for his role in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. Below is an excerpt from a transcript of the trial testimony given by Chambliss’ niece, Elizabeth Cobbs. The questions (“Q”) are asked by the Deputy Attorney General John A. Yung. The answers are provided by Cobbs. Arthur J. Hanes, Jr. is the defense attorney.

“Q. This defendant, Robert E. Chambliss—

A. Yes, sir.

Q. —said that he had enough stuff put away to flatten half of Birmingham?

Mr. Hanes, Jr.: Say it one more time.

Yes, sir.

Q. And, this was the day before the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church explosion?

Yes, sir.

... Q. What did he do after he put his hands on the newspaper?

He looked me in the face and said:

‘You just wait until after Sunday morning, and they will beg us to let them segregate.’”

Primary Source: “Birmingham bombers known, Post reports,” The Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution (GA), May 31, 1964, 16.

“Police know who bombed the Birmingham church in which four children were killed last September but cannot make an arrest for lack of evidence, it was reported today. The ringleader of the plot was not identified in the current issue of the Saturday Evening Post, which said ‘Mister X’ was under constant surveillance by police and federal agents who hoped to nab him eventually on a conspiracy charge. The article said they had little hope of being able to convict him of murder. ‘The FBI knows who brought the dynamite, who made the bomb, who placed it there, and who engineered the crime,’ Macon Weaver, U.S. attorney in Birmingham, was quoted as saying. The article also quoted Birmingham Chief of Detectives Lt. Maurice Hause as saying, ‘we know every detail about it, but we don’t have the evidence.’ Two men [Chambliss and Charles Cagle, another KKK member] were arrested in the case and fined $100 each and sentenced to 10 days in jail on charges of illegal possession of dynamite. The magazine also said ‘Mister X’ and his confederates had taken oaths to kill any member of their group who turns police informer.”

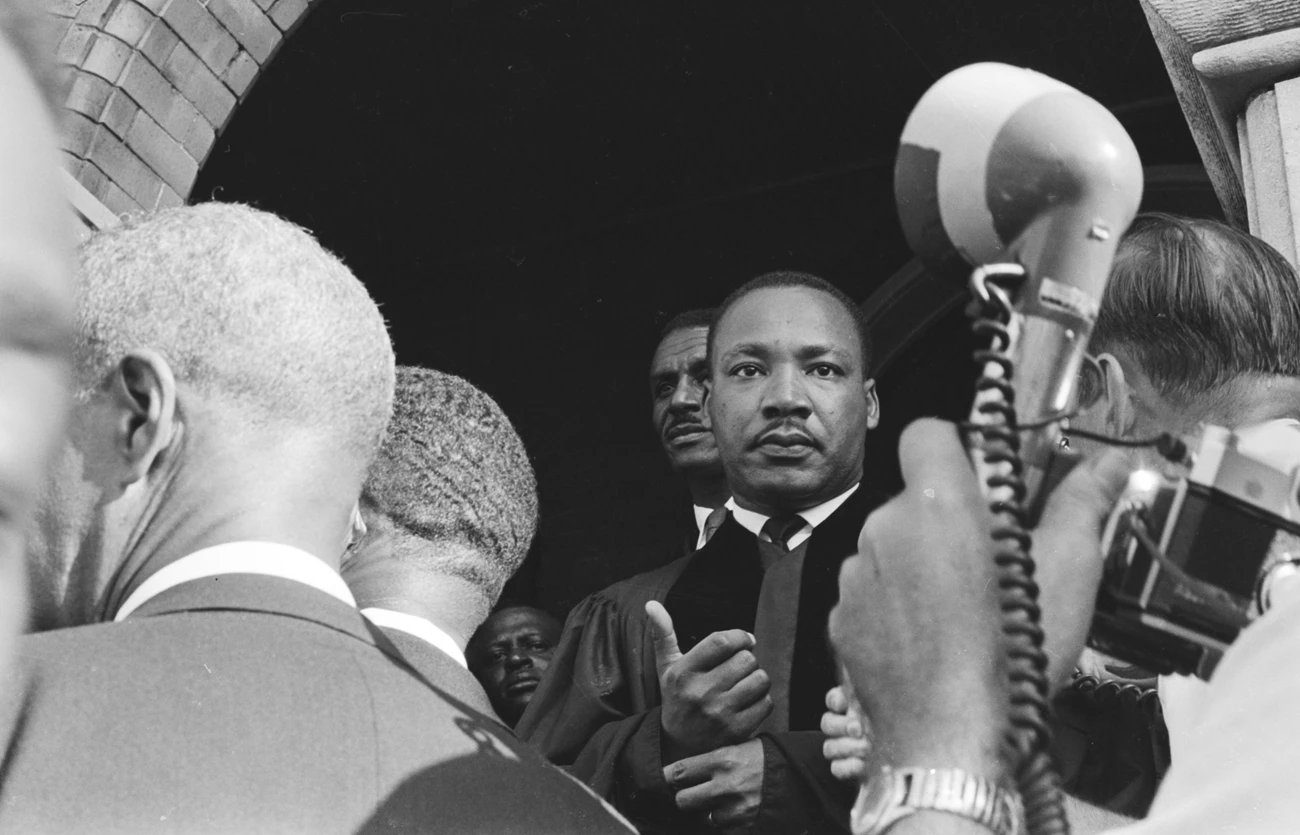

Primary Source: Rick Bragg, “38 years later, last of suspects is convicted in church bombing: ex-Klansman gets life sentence,” New York Times (NY), May, 23, 2002, A1.

[See photo above]

In the years following the Birmingham bombing, Bobby Frank Cherry boasted about his direct involvement in planting explosives at the 16th Street Baptist Church. His own words implicated him when he was later tried.

“When the crime was committed, when four girls lay blasted to death in the shattered basement of the 16th Street Baptist Church, Bobby Frank Cherry was young and strong and confident that his world, one of white robes and closed minds, would turn forever. This afternoon, more than 38 years after his bomb shook the church in the most shameful act of the civil rights movement, he stood old, angry, and puzzled as a mostly white jury sent him to prison for the rest of his life for the thing he once laughed about in the company of like-minded men. …Mr. Cherry’s conviction, after deliberations of more than six hours, brings to a close an often-flawed and often-abandoned investigation into the bombing, which—despite gaps of decades in its progress—has finally brought to justice all the men linked to the bombing who did not die before cases could be made. …Just feet away, the surviving family members of his victims, mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, sat in a single row of metal folding chairs, all dry-eyed, outwardly impassive. It was if they were determined to send Bobby Frank Cherry into the bleakness of his future without letting him see even one more glimpse of the pain that he had caused.”

Voices from the Field

"Trauma" by Riana Elyse Anderson, a professor of Health Behavior & Health Education at the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Photos & Multimedia

Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Vernon Merritt, Birmingham News.

San Francisco News-Call Bulletin Newspaper Photograph Archive, ca. 1915-1965, BANC PIC 1959.010--NEG, Part 3, Box 200, [09-18-63.04:05] © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Oregon Journal (OR), September 22, 1963. Courtesy of the Oregonian.

Thomas J. O’Halloran, photograph, September 22, 1963.

Writing Prompts

Opinion

Kenny disappeared into his secret hiding place behind the couch when the Watsons returned to Flint. Did Kenny’s behavior seem reasonable to you? In your opinion, what is the best way to process a disturbing or traumatic event? Link your opinion to words and phrases (e.g., in order to, for instance, in addition) to support your reasons.

Informative/explanatory

Research and identify the five main provisions in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Discuss what it means to outlaw discrimination based on these five provisions. Develop the topic with facts, definitions, concrete details, quotations, or other information and examples related to the establishment of this act.

Narrative

Introduce a real or imagined pet. Describe your pet and behaviors that are unique and/or problematic. Your pet encounters a challenging situation. Tell a story that follows a sequence that includes a setting, a problem, and a resolution. Orient the reader by establishing a situation and organize an event sequence that unfolds naturally.

Note: Wording in italics is from the Common Core Writing Standards, Grade 5. Sometimes paraphrased.

Last updated: January 8, 2024