Last updated: February 24, 2023

Article

Treaties To Take Indigenous Lands

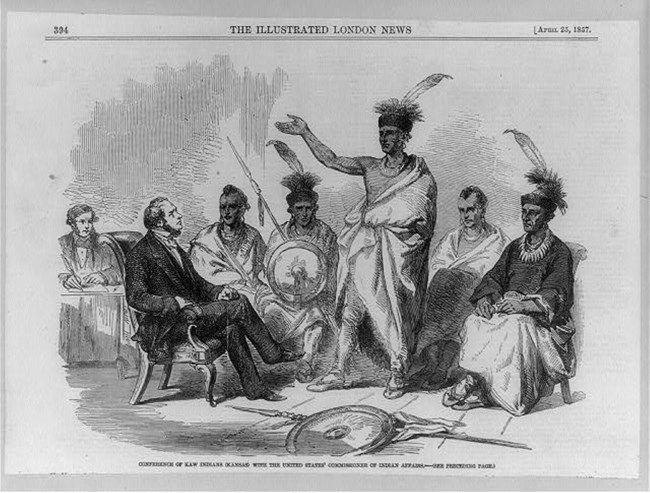

London Illustrated Times, as digitized by the Library of Congress.

William Clark described the plains of eastern Kansas near Independence Creek as “one of the most butifull Plains, I ever Saw.” He praised the “Leek Green Grass,” which he thought “well calculated for the sweetest and most norushing hay.” He described shrubs in every direction “covered with the most delicious froot.” He wondered that such beautiful scenery could exist so “far removed from the Sivilised world.” He dismissed the presence of the many Indigenous people in the region who had lived there and cared for the landscape since time immemorial.

Published accounts of the Lewis and Clark Expedition began to appear as early as 1807. They sparked the imaginations of Americans eager to move west, as the U.S. government had intended. This was all part of the design of American colonization.

To open these lands for White settlement, the U.S. government negotiated treaties with Indigenous leaders. If these leaders did not want to make treaties, the U.S. military used violent force until they changed their minds.

Kanza leaders signed a treaty with the U.S. government on June 3, 1825, which formally ceded to the United States a large amount of land in eastern Kansas. Many Kanza families were forced to move to an area along the Kansas River that was a tenth the size of their traditional homelands. The U.S. representative who negotiated this treaty was William Clark.

Kanza people signed additional treaties in 1846 and 1859, which further reduced their territory.

Clark’s 1804 description of the Kansas plains began a chain of events that culminated in the U.S. government, represented by Clark himself, forcing Kanza people to leave the “most butifull Plains” that they once called home.

About this article: This article is part of series called “Pivotal Places: Stories from the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.”