Last updated: January 14, 2021

Article

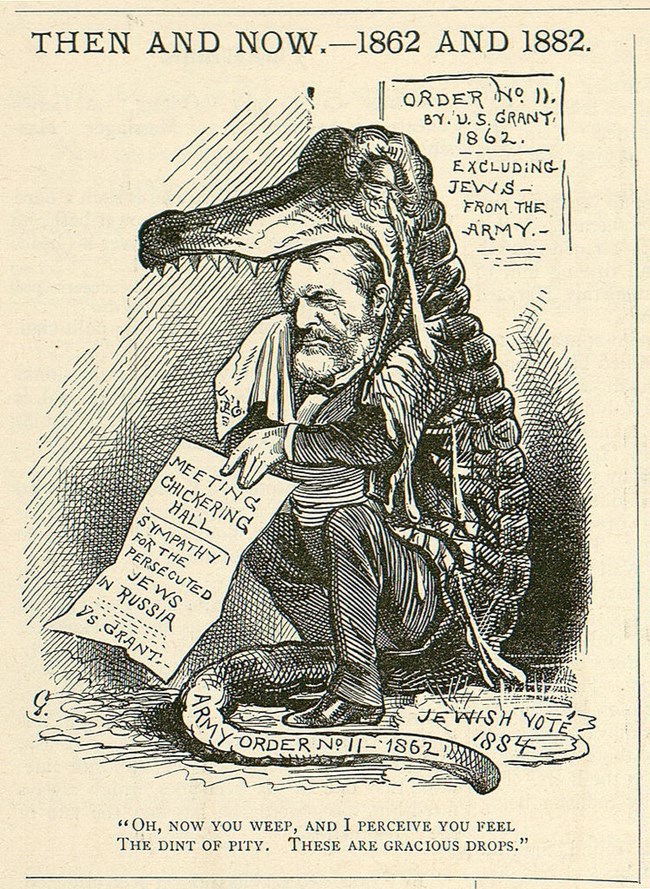

Ulysses S. Grant and General Orders No. 11

Library of Congress

At the beginning of the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln’s administration imposed a blockade against the Confederacy. The government’s blockade was intended to cut off the Confederacy from all trade with the North and other countries. By closing out the market for Southern goods such as cotton, rice, and tobacco, the Confederacy would run out of money and be more likely to eventually give up its effort to gain independence from the United States.

Some people were anxious to cash in by illegally smuggling resources into the North. Cotton speculators often followed the Union armies as they made their way south. They searched for planters who were willing to sell their lucrative crops for the best price, especially along the Mississippi River. Since these planters were cut off from markets by the blockade surrounding southern ports, they were often willing to sell their cotton to these questionable speculators. Even Union army officers were involved in helping speculators gain access to the cotton grown in the South. Many of the officers were getting extra money on the side by “greasing” the wheels of this illegal cotton trade.

The War Department worried that money given to the planters would end up in the coffers of the Confederacy, which would prolong the war. A compromise was eventually achieved to allow traders who held a permit to buy cotton so long as they did not travel into enemy territory to purchase the cotton. U.S. General Ulysses S. Grant found it very difficult to enforce the rules intended to stop illegal trading of cotton. He wanted to keep the traders from following his armies as he moved further into Mississippi. Grant’s father, Jesse Grant, inflamed his disgust with the traders when he tried to obtain a permit for purchasing cotton for Harmen, Henry and Simon Mack.

The Mack brothers were part of a prominent Jewish family from Cincinnati that owned a clothing business. Jesse Grant had agreed to take the Mack family to General Grant’s headquarters in Mississippi for 25 percent of the profits gained from the cotton they had hoped to obtain. General Grant was not happy with his father when he made this attempt to use his position as a military officer for monetary gain, and he was not happy with the Jewish clothiers who had tried to get a permit for purchasing cotton through his father. Grant denied the Mack family the purchasing permit and sent them back home. This incident may have been prominent in Grant’s mind when he issued General Orders No. 11.

On December 17, 1862, Grant issued General Orders No. 11, which stated: “The Jews, as a class, violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department, and also Department orders, are hereby expelled from the Department.” The order was immediately controversial and received condemnation from the Jewish community. At least thirty Jewish families living in Paducah, Kentucky (located within Grant’s military department) were forced to move from their homes. Newspapers heavily criticized Grant for his orders, and he was nearly censured by Congress. Politicians, including President Lincoln, were bombarded by the Jewish community with protests over Grant’s orders. There were many soldiers serving in the Union armies who were Jewish, and it did not seem to be right to be fighting for a country that was expelling their own people. President Lincoln immediately had General Henry Halleck order Grant to rescind General Orders No. 11. These orders became a stain on Grant’s reputation for the rest of his life.

Wikipedia

Was Grant anti-Semitic, or just trying to stop war profiteers from helping the Confederates? The way Grant wrote General Orders No. 11 makes it appear that he held anti-Semitic views since he expelled “The Jews as a class.” Grant’s adjutant, Colonel John Rawlins, was against issuing the order, and there are no records in the War Department suggesting that Grant was authorized to issue such an order. Grant wanted the government to purchase cotton at a pre-determined price, and then send it northward, which would have ended military and civilian involvement in the cotton trade. This would have gotten the traders out of the army’s way, and Grant could focus on defeating the Confederates within his department. Or perhaps the order was born out of frustration with his father’s actions. Nevertheless, historian John Y. Simon argued that “Jesse Grant’s involvement in the cotton trade provides a psychological explanation for the order, though hardly a justification. [Grant] expelled the Jews rather than his father.”

Grant never said much publicly about General orders No. 11, but he did express regret about issuing the order and offered an apology. In an 1868 letter to Jewish Congressman Isaac N. Morris that was later published in newspapers around the country, Grant stated that “I do not pretend to sustain the order . . . the order was made and sent out, without any reflection, and without thinking of the Jews as a sect or race to themselves, but simply as persons who had successfully . . . violated an order.” Continuing, Grant stressed that “I have no prejudice against sect or race, but want each individual to be judged by his own merit. General Orders No. 11 does not sustain this statement, I admit, but then I do not sustain that order.”

When Grant was elected to be President of the United States in 1868, he tried to correct his mistake through a number of different actions. He appointing a record number of Jewish Americans to government offices during his eight years as president. When the Adas Israel Congregation opened its new Synagogue in Washington, D.C. in 1876, President Grant attended the three-hour ceremony. Grant also spoke out against Jewish persecution in other countries. While some Jewish people continued to harbor resentment for Grant’s actions, many in the community actually felt that he had become a friend and defender of their rights. When Grant died in July 1885, the Philadelphia Jewish Record exclaimed, “ None will mourn his loss more sincerely than the Hebrew.”

Jonathan Sarna, When General Grant Expelled the Jews. New York: Schocken, 2012.

John Y. Simon, The Union Forever: Lincoln, Grant, and the Civil War. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012.

Jean Edward Smith, Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.