Part of a series of articles titled The Midden - Great Basin National Park: Vol. 20, No. 1, Summer 2020.

Article

Where Did Lehman Caves Dirt Come From?

This article was originally published in The Midden – Great Basin National Park: Vol. 20, No. 1, Summer 2020.

by Louise D. Hose and Harvey R. DuChene, Cave Geologists

We recently have determined that Lehman Caves passages and rooms formed through hypogenic (rising groundwater) processes and there is no evidence that surface streams ever flowed through the cave. Obviously, some surface drainage has entered through the natural entrance, but no streams flowed through the cave. The cave “scallops” common throughout the cave, once thought to be evidence of former rivers, are now recognized as “pseudo-scallops” and result from sulfuric acid condensation in a hypogenic setting (DuChene and Hose, this issue). Yet, clastic1 sediments (dirt) are scattered in several places throughout the cave. Where did they come from?

We recently have determined that Lehman Caves passages and rooms formed through hypogenic (rising groundwater) processes and there is no evidence that surface streams ever flowed through the cave. Obviously, some surface drainage has entered through the natural entrance, but no streams flowed through the cave. The cave “scallops” common throughout the cave, once thought to be evidence of former rivers, are now recognized as “pseudo-scallops” and result from sulfuric acid condensation in a hypogenic setting (DuChene and Hose, this issue). Yet, clastic1 sediments (dirt) are scattered in several places throughout the cave. Where did they come from?

The second, and probably very minor, source was insoluble material in the marble bedrock. However, the Pole Canyon Limestone is quite pure limestone and dolostone so this source is likely a trace contributor (Table 1, p.69).

A third source of dirt is clastic fracture filling in the marble. A shalesiltstone is exposed in the walls in several places in the Gypsum Annex, the northwesternmost part of the cave (Fig 1). Fractures filled with similar material are exposed in the ceilings in this region of the cave, as well.

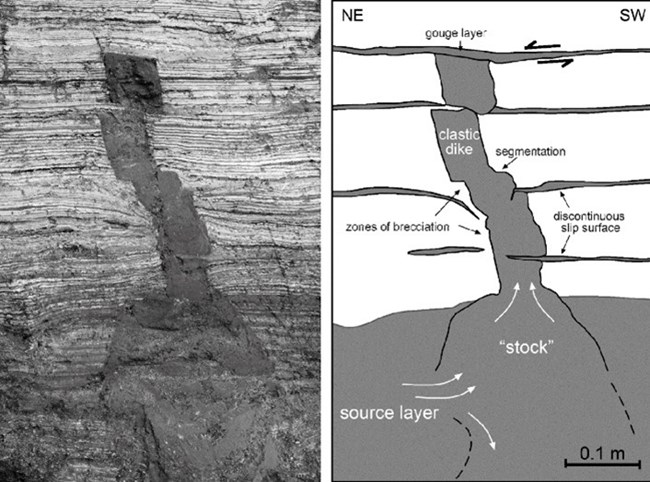

Diagram and photo from Weinberger et al. (2015-Conference proceedings)

Might similar clastic dikes within the marble be the potential source of the abundant “dirt” on the floor in Lehman’s Inscription Room? The abundant dirt in this area is uncharacteristic of the rest of the cave (away from the Natural Entrance) and a puzzle. A relatively simple study could be done, perhaps as an undergraduate senior thesis, to compare the Inscription Room floor “dirt” with the fracture filling material to see if they comprise similar mineralogy. It would also be profitable to map (and inventory) the exposures of clastic dikes and exposures in Lehman and Little Muddy Caves to see what insight their distribution might shed on the development of the caves. Any geology students interested in a fun project?

The fourth potential source of dirt, especially in parts of the Inscription Room, is the possibility that some of it was hauled into the cave by humans in the distant and unrecorded past. Only further study of the Inscription Room dirt will help solve the mystery of its origin.

Last updated: February 8, 2024