Last updated: July 8, 2023

Article

Why I Refused To Register

National Archives and Records Administration

The registration program became a crisis for individuals, families, and communities in Tule Lake. Incarcerees did not know what the consequences of their answers would be, but knew it could determine their futures for years to come.

There's no single reason behind the incarcerees' answers. This account, written several years later at an Army prison, explains why this anonymous person refused to register and answer the loyalty questionnaire.

Library of Congress

UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

Tule Lake Center

Newell, California

Community Analysis Section

March 31, 1944

(The following is a comment on the Registration program at Tule Lake and the Block 42 incident. It was written at the Leuppe Center.)

THE FACTUAL CAUSES AND REASONS WHY I REFUSED TO REGISTER

When registration ensued in the Tule Lake Relocation Center, I was aiding registration by interpreting and filling out the registration forms (Form 126A-Form 134A) for the registrants. I was employed at the time under Miss Phillips in the high school, teaching history and art. Miss Phillips was one of the registrars, as were all school teachers, so I happened to be assisting her in the performance of the duties of a registrar.

A week had elapsed since the inception of registration but the number of evacuees appearing voluntarily for registration was negligible. Many were suspicious of the real intentions of the army or the W. R. A. There were rumors that spoke of soldiers forcing the evacuees into their jeeps and taking them to the administration building and making them register. There were whispered stories of how a nisei girl would be shipped away and required to work in a negro hospital if she signed "yes". There were conjectures about having our properties "frozen" by the government—that they would use our signed papers as a means to that end. That they would use our signed statements in any way they so desired. There were persons who definitely declared themselves that they had been "duped" by the W. R. A. That when they had registered "no"—found their "no" answers changed to "yes" when they appeared at the administration building to demand the return of their signed registration papers. They explained that they wanted their papers back because from the uncertain rumors circulating then, they had decided it was safer not to have signed "anything". Above all this confusion and dilemma an announcement printed on paper issued forth from the project director, Mr. Coverley. The announcement stated that if a father of an American citizen nisei should advise his son or daughter against registration—his punishment for such a crime would be twenty-years imprisonment and ten thousand dollars fine. The camp’s reaction to this pungent declaration was similar to a lazy easy-going horse abruptly bitten by an enterprising bee. The residents assumed that any person who advised or conspired in a body or group against registration was also in the same category and liable to the same punishment.

Photographer: Clem Albers

National Archives and Records Administration

About eight days after the commencement of registration, there occurred an incident that many of us will not forget for a long time. An army of soldiers surrounded Block 42 and at bayonet points, plus light machine guns, captured thirty-five boys of that block. I have heard about this occurrence from on eye-witness. Tears swelled my eyes as I heard his description of the heart rendering scene. Where little brothers and sisters clung tenaciously to their departing brothers, tearfully hysterical in their demand to with to accompany them. Old men stood by helplessly, their eyes wet, dimmed, their lips hard pressed by angry teeth. Mothers pathetically waved farewells to boys whom they never expected to see again, their choked voices bade the boys "to take care of themselves—good bye”. Some men raised their voices above the tumult of the crowd and shouted lusty "Banzais" to impart to the departing boys that they would not be forgotten. All the residents of the nearby blocks attracted by the commotion in Block 42 amassed there and witnessed this distressing sight. Those that saw this commando style method of the army, hustling their prisoners into their trucks, were embittered with an impression that cannot easily be dismissed from their minds. As proof of this; ward 5, which is the blocks adjacent to Block 42, was nearly one hundred per cent in its refusal to register. The other wards in camp were not so well impressed so consequently they nearly all registered.

The reason the thirty-five boys were apprehended by the army was because the boys had signed a statement absolutely refusing to register. They had taken that signed statement to Mr. Coverley and presented him with it. They had caused no disturbance or violence while performing this act. They returned home safely that day and the army descended upon them the following night. As I look back now I think Mr. Coverley’s predilection was to "throw a scare" into the populace and inclined to the belief that "fear of the consequences" would force the residents to register. Compared to the accomplishments of the other relocation centers, Mr. Coverley’s methods resulted in a dismal failure of registration at Tule Lake.

Photographer: Dorothea Lange

National Archives and Records Administration

These people had evacuated the pacific coast peacefully and obediently because they were instructed by the defunct J. A. C. L. that to do so was to aid America in her war effort. Their beloved homes and livelihoods were swept away as if by a whirlwind tornado.

All my life, ever since I could remember, my father and mother worked, sweated and saved pennies so that our family could eat and have a roof over our heads. When they grew old with gray hair, they were still working. They managed to own a small hotel with their life’s work invested in it. I appreciated their loving endeavors on my behalf so I labored to help my aging parents in our hotel. Then suddenly came evacuation. I could not believe it would happen to us until it actually came to the days before evacuating. Most of us sold our businesses and our household appliances for practically nothing, because we were pressed for time and there were so many of us that wanted to sell out. Our life’s dreams and hopes evaporated overnight. We were transported to reception centers after being issued a number and a doctor’s physical examination certificate. I felt as if I was being treated as an alien. Most of us were walking around in a daze those days. We thought it was some fantastic dream and kept hoping that we would wake up and discover that it was only a dream. It required us many days to become accustomed to the routine of restricted camp life and to the cold reality of things.

Among the foremost fundamental specifications of occidental psychology are the words to the effect that the reason, emotions, and actions are motivated by the effects of a persons, environment. Brother—behind barbed fences I assure you our reasons and acts were not exactly according to Hoyle. Living in a confined area day in and day out naturally tended to irritate a person’s mind upon the slightest pretext. Crowded into limited quarters, human nature begins to gasp for a wider space to breath in. A person eventually begins to find fault in others. They become sick and tired of viewing the self-same characters every day. The aloof and resentful attitudes of some of the W. R. A. personnel did not help relieve the emotional tension bubbling upwards hourly. Small and petty jealousies, personal enmities, misunderstandings between the W. R. A. and the evacuees, the heart rendering disappointments and disillusionments caused by evacuation and the harsh treatments encountered when behind barbed wire fence—all added up arithmetically so when registration was instituted, the average mental make-up of the evacuee was, "don’t trust the W. R. A." This is proved by the fact that in the first week of registration, even American educated niseis, excepting kibeis, did not register, when asked to do so voluntarily. Those that did so were in the negligible minority. They only started to register in huge scores when the W. R. A. commenced to call the registrants to the personnel recreation building, block by block, males on certain dates and females on specified dates.

After all their hardships the populace of Tule Lake was stirred with indignation at the army’s unnecessary method of apprehending the boys of Block 42. Needless to say, I was aggravated too. I decided not to register. If they were treating those boys like prisoners for refusing to register— then I would join them too. With deep conviction in the righteousness of my cause and with a firm reliance on the protection of divine providence, I acted against registration. To the humanity living in a normal American community, the beliefs and actions of the evacuees in the centers may sound and appear mediocre but to us, the residents of the centers—our hopes, our misfortunes, our troubles appear immense because we are part of its life and existence. Those thirty-five boys taken at bayonet points were not just a couple of dead-end kids—they were a symbol of our resentment against oppression. The suppressed emotional bitterness that was boiling upwards had to have an outlet and this was it. Many Japanese young men who in normal life would have been ashamed at their own rash actions took the opportunity to bash a few heads in. It did not matter whether they had proof or not—just a hearsay was enough. Inus, dogs or suspected stool pigeons, were attacked hither and yon. The once quiet camp of Tule Lake was thrown into a pandemonium. I heard that even a minister was assaulted. Oh well, I guess in these days of ammunition passing preachers, anything can happen.

The supreme court may pronounce the military evacuation of the Japanese from the Pacific coast legal, but there are some things that are not, cannot be ably controlled by judicial connivances and that is human emotion and reason.

National Archives and Records Administration

My brother had volunteered and enlisted in the American army almost a year before Pearl Harbor. For my brother’s sake and because America is my birthplace, I harbor no ill will towards this country. I am classified as a Kibei and labelled a pro-Axis. It is strange indeed to be gazed upon with suspicion when I am not in a position to do harm. I have never published propaganda, nor organized a "Bund" or spoken against the government of the United States while living in Seattle those many years. My father, mother, and sister are now residing in Japan; that is the basic reason why I will not fire a gun against Japan. Of a certainty I will gladly work for America on the production front, but I will not bear arms against my father’s country. I will not bear arms against America either.

To some of those W. R. A. officials, who with their resentful attitudes toward the evacuees, and who added to and made the aggravated situation worse, I would like to leave a joke that will be helpful to them in the future when they have to deal with human beings.

Lum and Abner upon their first visit to the big city in an old car stop at a garage for gas. Lum calls out, "Hey, is thar ennyone hereabouts?" The attendant appears and with a glance at their jalopy sneers and grunts, "Whadda ya want?" Lum and Abner stare at each other dejected. Lum says, "Gorsh he sounds like a man with a Guv’ment job, don’t he?".

Strange that the words of Jefferson, should intone on the border of treason to an America at war. But I wish to close with an excerpt from Thomas Jefferson’s most vibrant words because it fully expresses my ideals and sentiment. In his time his minority was the oppressed minority—in my day, the minority I belong to is in a similar circumstances.

"I have sworn on the altar of God Eternal, hostility to every form of tyranny over the mind of man.

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights; among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

National Archives and Records Administration

Post Script:

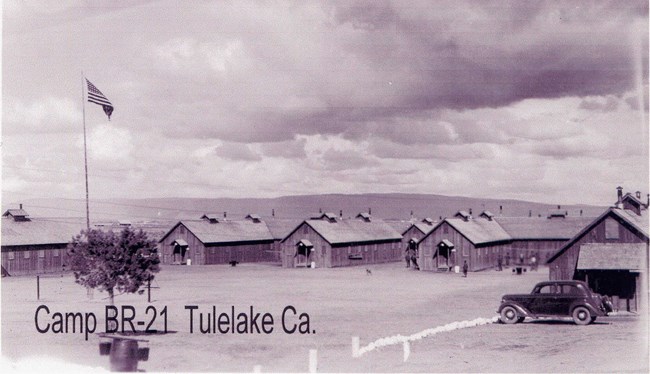

I did not go in detail about my experiences in the Klamath Falls Jail, the Tule Lake Isolation Camp [also known as Camp Tulelake] or Leuppe Isolation Camp because all I wanted to set forth here is my reason for refusing to register. I realize I am putting the blame of all camp disturbances on the W. R. A., but I will be ready at all times to take any rebukes coming to me if the W. R. A. thinks I do so unjustly. I do not like to beat around the bush, I call a spade a spade.

National Archives and Records Administration

A GENERAL SUMMARY OF THE "REGISTRATION INCIDENT" AT TULE LAKE

When the accompanying problems adjacent to Registration first appeared in Tule Lake, W. R. A. did not signify to the residents that it was in any way a W. R. A. ordinance. Six army sergeants and a gray haired lieutenant brought the registration papers "direct from Washington" so they stated when the army officers called a general meeting among the evacuees in camp—explaining the whys and wherefores of the said registration. They informed us that this registration was directed from the Federal Man Power Commission in Washington. As registration day opened on February 17, 1943, the residents did not respond to their requests that the evacuees register voluntarily.

Several days following the commencement of registration the number of registrants appearing to register was negligible. Thereupon the Project Director, Mr. Coverley, issued a statement on February 19th specially printed on a white sheet of paper. This statement accompanied the Tule Lake camp newspaper upon its delivery. It warned the fathers of niseis "not to advise" their American citizen sons or daughters against registration. The punishment for such a crime was twenty years imprisonment and ten thousand dollars fine. When such a vigorous allegation was discharged by a Project Director, that was aloof and miscomprehended by the populace, the result was more conjecture on top of misunderstanding.

On February 20th a group of thirty-five young boys, all residents of Block 42, signed their names to a statement that they had devised themselves, manifesting themselves against registration and absolutely refusing to register. The thirty- five boys marched into the administration building and presented the Project Director with the above statement. As far as is known, there was no violent scenes, no disorder and the thirty-five boys returned to their respective residences without incident that day. Those boys might have been trying to test the statement and threat issued by Mr. Coverley warning their fathers not to confer advice to their sons against registration. Perhaps the boys thought it was a "bluff ". Perhaps Mr. Coverley devised to impress or rather "throw a scare" into the evacuees and abruptly called out the army.

Among memories of Tule Lake, the night of February 21st will long be remembered by the residents. The above mentioned thirty-five boys, the majority of them aged seventeen, eighteen years were taken to Alturas County Jail at the point of bayonets. They were apprehended by an army of soldiers equipped with light machine guns, tear gas bombs and fixed bayonets. The prisoners were all residents of Block 42. The Commando equipped soldiers had surrounded that block and without much resistance had captured the thirty-five boys. When all this armed might was being displayed there, the residents of the nearby blocks all gathered around and witnessed many pathetic, tearful scenes. They observed the capture of American citizen niseis by American soldiers. It might be specified here that the majority of those thirty-five prisoners were American educated niseis, there were only three Kibeis among them.

These people had evacuated from the pacific coast peacefully and obediently because they were told by the so-called J.A.C.L. that to do so was to aid America in her war effort. All their livelihood, their treasured homes, their fortunes were sacrificed so that America might be benefited. All those men, women, and children, brothers and sisters that looked on that night of February 21st will not forget the sight. After being forced to live behind barbed wire fences for nearly a year, this act of unnecessary sword-rattling was insult upon injury. Their faith in Democracy’s so labeled, ''with liberty and justice for all" was beginning to wave a little before their very eyes. There is a limit to human endurance, mankind will concede that. Many cried as they waved farewells to boys that they expected never to see again. Many little kid brothers and sisters clung to t heir elder brothers— sobbing and hysterically screaming that they wanted to go with them. Soldiers tore them apart as they were arrayed into the awaiting trucks. Countless people shouted "Banzais" to express to the departing young boys that they will not be forgotten.

That night and the nights and days following, the once peaceful camp of Tule Lake was a bedlam of activities and commotion. Tule Lake was a scene of mob violence, convulsive meetings, and the likes of a town in Ireland after an election day.

To the Japanese mind—the army’s provocation was an indignity and a challenge. So they accepted the challenge and all those having conviction and courage had flatly refused to register, taking the similar stand as the thirty-five young boy prisoners of Block 42.

So it came to pass that because of a blind personnel staff at the Tule Lake Relocation Center, and a small error that could have been avoided— the registration at Tule Lake was a dismal frustrated failure, compared to the accomplishments of the other relocation centers.

The main point of the whole disturbance and unrest that swept Tule Lake in those hectic days was the high-handed method employed by the Project Director in apprehending those young boys from Block 42. Thereafter the issue and question of registration became of secondary importance.