Last updated: January 24, 2018

Article

Barbarians at the Gate: Biting Flies of Beringia

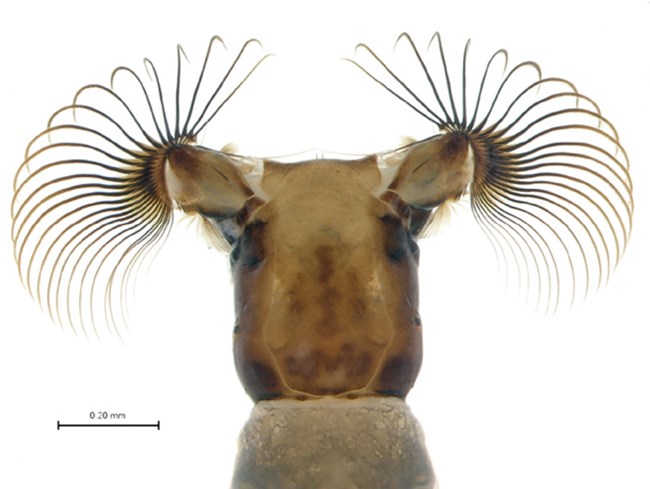

Photo by D. C. Currie

For blood-sucking flies, the Far North is a paradise of food and breeding habitat, but for the animals and humans that reluctantly furnish the blood, the Far North is hell on Earth. The world’s largest populations of black flies and mosquitoes are found in northern regions of the globe, where densities of larval black flies can exceed 600,000 larvae per square meter of streambed, and populations of even a single species of mosquito can reach unsettling densities of more than 30 million adults per hectare. Legendary for their blood-sucking habits and noxious behavior of ceaselessly swarming around their hosts, biting flies are responsible not only for enormous economic losses but also for the limited extent to which northern regions have been inhabited and developed (Adler et al. 2004). They can suppress tourism and gouge the economy of afflicted communities. They can be so vexatious to wildlife that the timing and extent of migrations of animals such as caribou are significantly altered. Biting flies also routinely transmit microorganisms that cause wildlife diseases such as avian malaria and leucocytozoonosis.

Photo by M. Pepinelli

Photo by D.C. Currie

Photo by M. Papinelli

Photo by M. Pepinelli

Although Beringia was the main source area for black flies that repopulated northern North America after deglaciation, it also received a substantial number of immigrant species from southern refugia. Among these immigrants are several major pest species of humans and domestic animals. These immigrant pests boil from the rivers and streams of eastern Beringia, yet none have managed to cross the Bering Sea into easternmost Russia. But the barbarians are at the gate.

Our previous work has shown that distances of less than 62 miles (100 km) are not a major obstacle to black fly dispersal (Adleret al. 2005). Species, including pests, from southern areas of North America have worked their way northward following the Wisconsinan glaciation, a process likely to continue with global warming. Insect including biting flies, with their strong dispersal abilities and short generation times, track climate change far more quickly than most organisms. One of these species, Simulium vittatum, is among North America’s most abundant and widespread black flies and is a significant pest of humans and large mammals. This species and others are poised to colonize the opposite side of the Bering Strait. We now have the baseline data to monitor ongoing changes in the Beringian biting-fly fauna as climate change continues.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Shared Beringian Heritage Program of the National Park Service, which supported the research of Adler, and the ROM Reproductions Acquisitions and Research Fund, which supported Currie. We also thank Mateus Pepinelli for the photomicrographs of some of our specimens.

REFERENCES

Adler, P.H., D.C. Currie and D.M. Wood. 2004.

Adler, P.H., D.C. Currie and D.M. Wood. 2004.

The Black Flies(Simuliidae) of North America. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, NY.

Adler, P.H., D.J. Giberson, and L.A. Purcell. 2005.

Insular black flies (Diptera: Simuliidae) of North America: tests of colonization hypotheses. Journal of Biogeography 32:211-230.

Darsis, R.F., Jr., and R.A. Ward.2005.

Identification and Geographical Distribution of the Mosquitoes of North America, North of Mexico. University of Florida. Gainsville, FL.

Malmqvist, B., P.H. Adler, K. Kuusela, R.W. Merritt, and R.S. Wotton. 2004.

Black flies in the boreal biome, key organisms in both terrestrial and aquatic environments: a review. Ecoscience 11: 187 - 200.