Last updated: March 30, 2021

Article

Battle of Fort Sumter, April 1861

Library of Congress

President Lincoln Orders US Navy to Fort Sumter

"I am directed by the President of the United States," a letter to Major Robert Anderson, the US Army commander of Fort Sumter, read, "to notify you to expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only, and that if such attempt be not resisted no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice, or in case of an attack upon the fort." A copy of the letter was also delivered to Governor Francis Pickens of South Carolina. Confederates, previously hopeful of Fort Sumter's evacuation, now felt betrayed by the sudden shift in President Abraham Lincoln's administration.

"Diplomacy has failed," a southerner wrote to Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard in Charleston. "The sword must now preserve our independence." The Confederate Secretary of War, Leroy P. Walker, telegraphed Beauregard on April 10 with instructions to demand the evacuation of Fort Sumter as soon as he was certain that President Lincoln’s resupply order was genuine. If the demand were refused, the general was to "reduce" the fort. Beauregard replied that the demand would be presented at noon the next day, April 11.

Confederacy Demands Fort Sumter's Evacuation

Three of General Beauregard's aides, James Chesnut, A. R. Chisholm, and Stephen D. Lee, delivered the general's message to Anderson. If Anderson marched his men out of the fort, they could take their arms and private property. He might also fire a salute to his flag, and Beauregard would supply him with transportation to any US Army post that he chose. Anderson read the demand and asked for time to consult with his officers. They joined him in unanimous defiance, and the major drafted a polite refusal. As he handed it to the three aides, he remarked that if the Confederates did not batter the fort to pieces, the garrison would be starved out in a few days anyway.

Chesnut, Chisholm, and Lee carried back both the written message and the oral communication, which they supposed Anderson might have meant as an unofficial plea for time. Beauregard consulted with officials in Montgomery, and late that night he sent his emissaries back to the fort with another proposal. If Anderson would specify an hour when hunger would force him to evacuate and would promise not to fire unless fired upon, the Confederates would not bombard the fort.

This message reached Anderson after midnight. The major took his time formulating a reply, and in the early hours of April 12 he presented them with his answer: he calculated that he would evacuate at noon on Monday, April 15, unless he were resupplied by that time. That proved unacceptable, for the Confederates wanted to prevent the arrival of the supplies and end the crisis. The Confederate officers left the fort at 3:20, warning Anderson that the bombardment—and, inevitably, civil war, would begin in one hour.

Some six thousand Confederate troops encircled Charleston Harbor that morning. Several dozen cannon and mortars bore on Fort Sumter. Fort Sumter boasted more than four dozen usable guns, but the garrison could man only a few of them at a time.

Library of Congress

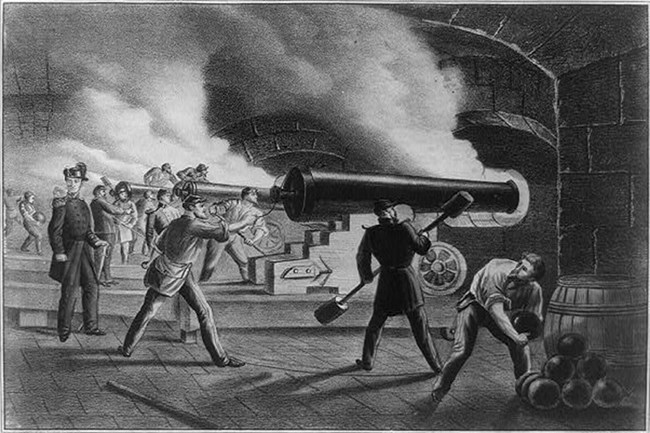

First Shots

On their way back from Sumter, the aides Chesnut, Chisholm, and Lee stopped at Fort Johnson to inform Captain George S. James that he might fire a signal gun at the specified time. At 4:30 in the morning, at Fort Johnson, a gunner in James' mortar battery pulled the lanyard on a ten-inch mortar. The projectile arched high over the harbor, bursting in midair over Sumter. Major Anderson's men made their way to shelter, and the citizens of Charleston began climbing to their rooftops for a better view of the battle. A few more guns opened up here and there, and within half an hour every Confederate battery in the harbor that could reach Fort Sumter was firing at it.

The Sumter garrison stood to reveille that morning in the bombproofs instead of on the parade. Anderson divided his men into three reliefs, each of which was to work the guns for two hours. Anderson could count only seven hundred cartridges in the entire fort, and six men were already busy sewing new ones from blankets and spare uniform parts.

Because of the shell fragments flying about the parapet, Anderson decided against using the guns on the barbette tier. The decision severely hampered the fort's ability to respond, for all the big guns lay on the barbette. The first shift stood to its guns at 7:00 A.M. Captain Abner Doubleday aimed the first gun, choosing one of the 32-pounders in the right gorge angle. He trained it against the armored battery on Cummings Point, and the solid shot flew accurately enough, but it bounced harmlessly off the ironwork.

The garrison ceased fire once the light was gone, and the surrounding batteries slackened their fire as well, reverting mainly to occasional mortar rounds. Captain John G. Foster, Captain Truman Seymour, and Samuel W. Crawford ventured out on the esplanade to inspect the damage, and their opinions varied according to their perspectives. Foster, the engineer, found "that the exterior of the work was not damaged to any considerable extent," while Crawford, the surgeon, saw holes more than a foot deep in the brick walls, especially on the side facing Cummings Point, and judged the effect of the enemy's shells "great."

Library of Congress

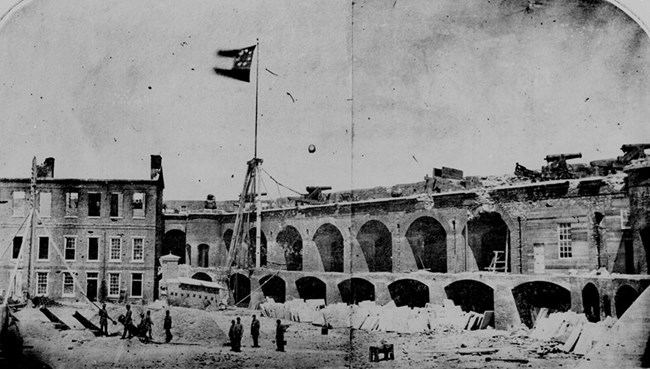

Fall of Fort Sumter

On the second day of the bombardment, Confederate hot shot, fired from Fort Moultrie, set Fort Sumter aflame. The fire began on the roofline of the officers’ quarters on the gorge wall. The burning barracks so threatened the magazine that Captain Foster asked permission to pull out what powder they needed. There were about three hundred barrels of powder inside, and with the help of off-duty officers he rolled about fifty of them into different casemates. Then the flames came so close that they closed the door and buried it with dirt.

By late morning the men inside Fort Sumter all lay face-down in the casemates with wet handkerchiefs pressed to their faces. Confederates on Morris Island were so impressed with the defenders' tenacity that they cheered every shot from Sumter.

The rising column of smoke inspired the Confederates to greater efforts, and the shells rained in even faster. At about 1:00 P.M., a shot snapped the flagpole and brought the Stars and Stripes to the ground. Lieutenant Hall removed it from the pole fragment while Lieutenant Snyder, Peter Hart, and one of the laborers erected a temporary flagstaff on the parapet in the middle of the right face, looking toward the open sea.

The falling of the flag inspired a Confederate officer on Morris Island to make a diplomatic effort. Louis T. Wigfall, a former US senator from Texas, had returned to his native South Carolina to help the secessionist cause. Though he carried a commission as colonel on Beauregard's staff, he was acting strictly on his own when he hopped into a rowboat on Cummings Point, ordered in a private soldier and two enslaved people, and instructed them to row for the fort.

Wigfall represented himself to Anderson as an envoy from General Beauregard, who wanted the bombardment stopped. Anderson replied that he had told Beauregard what terms he would require but added that he would leave the fort immediately rather than waiting until April 15. Wigfall, satisfied, returned to Cummings Point with the news.

The harbor fell silent at about 1:30 that afternoon. A few minutes later another boat docked at the wharf, carrying the same Captain Lee who had brought the original evacuation demand and two new emissaries. They presented themselves to Anderson as General Beauregard's messengers, having come because the garrison flag was down and a white flag had been shown at one of the embrasures. Anderson explained Wigfall's visit and mission, but they told him that Wigfall had not been anywhere near General Beauregard for some time. They were the only authorized representatives, they insisted.

Angry, exhausted, and confused, Anderson said he would have to resume firing. The three dissuaded him, asking for a written version of the same terms he had dictated to Wigfall. The major agreed not to open fire again until Beauregard had had a chance to accept or refuse the conditions. Word came back at last that the conditions were acceptable to Beauregard. The garrison would leave after firing a salute to the tattered flag they had defended.

Library of Congress

Evacuation Ceremony & Confederate Victory

Major Anderson planned to fire a hundred-gun salute to his flag, but the cartridges had to he improvised from scrap flannel. A small steamer waited for them at the wharf on the afternoon of April 14 while Anderson's soldiers gathered on the barbette tier. Cartridges lay piled around the guns, and at 2:00 p.m. the salute began.

Each crew had fired numerous rounds when a stray spark prematurely ignited one charge. The accidental explosion killed Private Daniel Hough and touched off several other cartridges that lay nearby. Five other members of Company E went down in the blast, and the ceremony stopped abruptly while comrades carried the victims to the parade. Once they were safely down, Major Anderson ordered the salute cut short at fifty rounds.

Crawford found that he could treat the three least severely wounded soldiers, but Privates George Fielding and Edward Gallway were too badly hurt to evacuate with their comrades. Gallway died at Chisholm's Hospital in the city; Fielding would go home a few weeks later, minus an eye. On April 15, 1861 the surviving US Army personnel departed Charleston Harbor for New York where thousands of cheering Americans greeted them upon their safe arrival.

Anderson reported the outcome of the battle to Secretary of War Simon Cameron enroute to New York:

"Having defended Fort Sumter for thirty-four hours, until the quarters were entirely burned, the main gates destroyed by fire, the gorge walls seriously injured, the magazine surrounded by flames, and its door closed from the effects of heat, four barrels and three cartridges of powder only being available, and no provisions remaining but pork, I accepted terms of evacuation offered by General Beauregard, being the same offered by him on the 11th instant, prior to the commencement of hostilities, and marched out of the fort Sunday afternoon, the 14th instant, with colors flying and drums beating, bringing away company and private property, and saluting my flag with fifty guns."