Understanding [bears] is the first step to conservation and peaceful coexistence. Only through knowledge can we avoid conflict, recognize their needs, and learn to fully appreciate these monarchs of the wilderness. Their future is in our hands. Matthias Breitter

NPS Photo / Ken Conger

After counting birds along a survey route through dense forest on the west side of the Teklanika River, the biologist hiked back to the river’s edge where travel would be easier. She was intent on reaching the road, not paying attention. Something made her look up.

At that moment, a young grizzly bear lifted his head not even 30 yards (27 meters) ahead. She stopped dead in her tracks, waved her arms above her head, and shouted “Hey, bear!” The bear could not identify her from smell—because her scent drifted in the opposite direction—so his tactic was to stand on his hind legs to get a better visual sense of what was there. Her training in how to handle a bear encounter paid off—she stood her ground and continued to shout and wave. The bear soon figured out that likely she was not a threat or easy prey and ran off. She left in the opposite direction.

Bear management is really people management

The encounter described is not uncommon in Denali National Park and Preserve. In Alaska and in the park, you are in bear country. Grizzlies move along river corridors and ramble across tundra habitat, but may hunt spring moose calves in spruce forests. Park visitors are less likely to see a black bear, but the odds are highest in forests near the park entrance and in Kantishna. Wildlife staff encourage people to do the right thing around bears. When people store food and trash properly, make noise while in areas of low visibility, and keep a safe distance from bears, there is seldom conflict. Denali sets a minimum distance to keep away from bears as 300 yards or 274 m. With an acute sense of smell, a bear may detect an attractive odor (not even noticeable to humans) from a mile away. Running up to 35 mph (56 km per hour), a bear can close the 300-yard gap in less than 20 seconds.

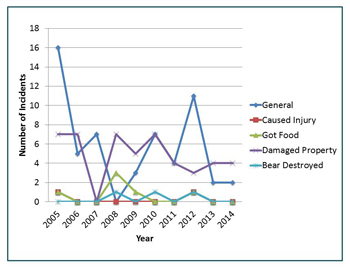

Park managers use a database called BHIMS (Bear- Human Information Management System) to track interactions between bears and people (see graph on reverse) over the years. Park users are encouraged to report any bear-related interactions. The interaction the biologist had with the bear would be classified as an encounter (the bear was aware of the human and changed his behavior), but needs no park management followup.

Any time a bear damages property, acquires food, makes physical contact with a human, or approaches multiple times within 10 yards (9 m), this is considered an incident. Reporting incidents helps managers identify problem areas and take any appropriate actions. If a bear damaged a tent in the backcountry, trained staff would hike to the site, set up camp, and wait nearby. If the bear returned and messed with the “planted” gear, staff might use aversive conditioning, a widely-used method of “training” bears from the undesired behavior. The scare tactics might include firecrackers or shooting rubber bullets. The details of management related to bears are outlined in the park’s Bear-Human Conflict Management Plan. Wildlife staff work with rangers to implement the use of bear-resistant food containers and post Keep Wildlife Wild signs.

Bear research in Denali

In addition to activities that keep bears and people safe in the park, wildlife staff also conduct studies to help answer questions about behavior (movements), population density, productivity, and survival. They place radio collars on selected bears, to find them later, and to collect data. Bears are darted from a helicopter, and biologists move quickly to take measurements and attach a radio collar while the bear is immobilized. Conventional radio collars send a signal, unique for each collar. At important times in the seasonal life of bears, biologists can locate each animal using radiotelemetry from a small airplane. Global Positioning System (GPS) “store on board” collars store data that is downloaded after the collar is retrieved (programmed to fall off or removed).

NPS Photo / Ken Conger

Basic grizzly population information

From 1991 to around 2009, biologists fitted grizzly bears in the central part of the park with radio collars. By observing individual bears over time, biologists learned that most females (sows) have their first litter of cubs at about seven years of age. Most sows have two cubs. Cubs usually stay with their mother until the age of three or four, when they strike out on their own. Only about 35 percent of the cubs born each year survive their first season. Sows live 30 years or more, giving them lots of opportunity to produce young that survive. Despite the low cub survivorship, the grizzly population is relatively stable. From bear surveys during those years, biologists estimate that 300-350 bears live in the park on the north side of the Alaska Range.

South side study—everybody likes salmon

During 1998-2000, biologists studied bears and their use of different habitat types on the south side of the Alaska Range, to help with planning of visitor facilities. Selected grizzlies and black bears wore GPS radio collars until fall, when park staff removed the collars and downloaded the data. During capture, they collected shavings from a claw to analyze for carbon isotopes that indicate the types of food (fish, meat, plants) in the bear’s diet. Southside grizzlies predominantly ate salmon, while black bears primarily ate vegetation—except when salmon abundance was very high. In general, because they are twice the weight of black bears, grizzlies can exclude black bears from preferred food sources. The presence of grizzlies reduced black bear access to salmon; when this happened, black bears ate foods that were less nutritional or ones that required more energy to process. Knowing the importance of salmon to both species will aid in the location of campsites and trails away from key salmon streams.

Are bears deterred by the park road?

In 2006, 20 bears were collared along the park road corridor to detect their activity in relation to traffic patterns. These bears wore GPS collars for one season. Bears crossed the road at all hours of the day (see graph at right, above). Peak crossings occurred when traffic levels were moderate to high, probably because bears are most active during daylight hours when traffic levels are also high.

Crossing the north park boundary

Starting in 2009, wildlife biologists fitted bears in the northeast portion of the park with GPS collars to follow their movements and determine how often they traveled outside the north boundary, where they might be vulnerable to high levels of hunting on Alaska state land. Based on inital data analysis, the collared bears rarely forayed outside the park (see map with colored dots at left). Biologists have since captured bears closer to the boundary to determine if those bears are any more likely to roam outside the park. All collars will be removed in September 2015 to analyze the data and complete this project.

A great divide, or is it?

Park managers are planning a new study in the southeast portion of the park beginning in 2017. Two bears in the 2006 road corridor study crossed the Alaska Range and spent considerable time in an area where subsistence users are authorized to hunt. To understand movements of bears across the Alaska Range and to and from southside areas where they may be harvested, biologists will fit 20 bears with GPS collars. Managers will use bear location data from this project to evaluate the interchange between bear populations on the north and south sides of the Alaska Range. In addition, researchers can construct habitat selection models from bear movement data to help predict potential changes in bear habitat use that might occur because of climate change’s effects on vegetation.

Understanding and respecting bears

Park managers rely on information collected in research studies to learn about bear populations and behavior, and to help bears and people co-exist safely without conflict in the park. The biologist near the Teklanika River surely breathed a sigh of relief knowing she—and the bear—were safe after their surprise encounter.

Last updated: August 18, 2016