Last updated: June 4, 2024

Article

Archeology and Industry: Gold Mining in Glen Canyon

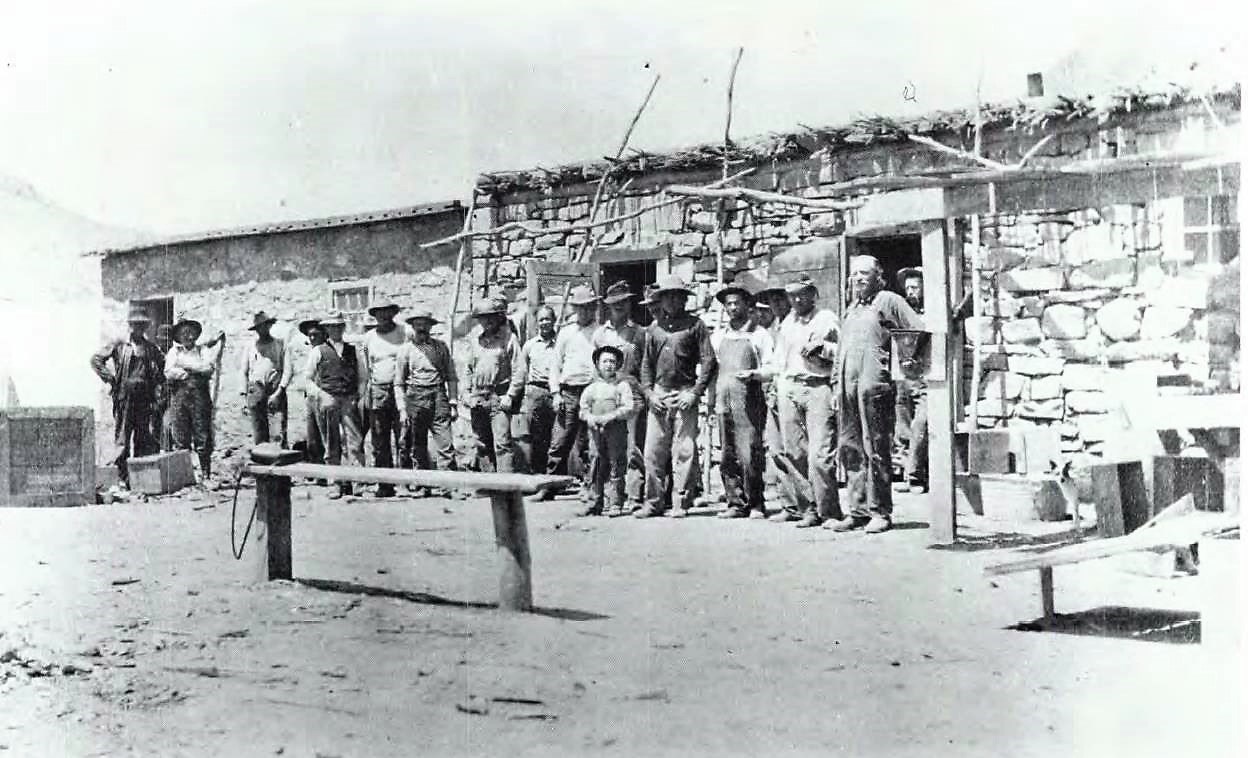

Carrell, Bradford, and Rusho, Fig. 3.1

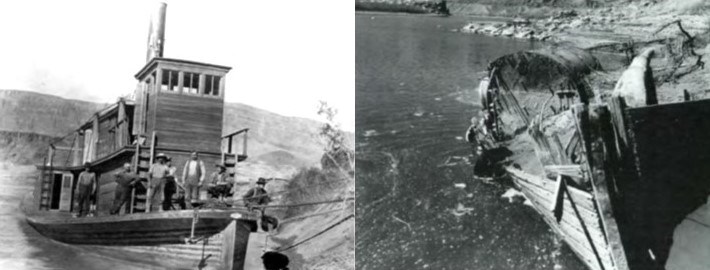

Carrell, Bradford, and Rusho, Fig. 3.25

Along with these structures, archeologists at Glen Canyon located artifacts and features directly connected to Spencer’s mining business. These include two boilers, 18 flume support pieces, a hose piece, and two small cuts or platforms on the hill slope where sleds or frames for monitors or hose nozzles were placed for the sluicing process. The Charles H. Spencer paddle-wheel steamboat transported coal in for the boilers from the Warm Creek mine, 28 miles away.

Carrell, Bradford, and Rusho, Figs. 6.2 and 6.5

Over the past decades, archeologists have monitored the wreck and other materials from the Spencer mining era. Today, visitors to the Glen Canyon Recreational Area can walk down the interpretive trail and view the remains. While just over 100 years old rather than thousands, these materials offer insight into an important era within Glen Canyon’s long history.

Carrell, Toni, ed., James E. Bradford, and W.L. Rusho. Submerged Cultural Resources Site Report: Charles H. Spencer Mining Operation and Paddle Wheel Steamboat. Southwest Cultural Resources Professional Papers No. 13. Southwest Cultural Resources Center, National Park Service, 1987.