Last updated: December 28, 2022

Article

Heeding the Call: Birding by Sound

NPS / K. Miller

“… four calling birds, three French hens, two turtle doves, and a partridge in a pear tree.”

Birds of many feathers are named in the popular, 18th century counting song, “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” This winter season brings another mirth-filled reason to count birds.

Beginning in 1900, from December 14 through January 5 the National Audubon Society holds the annual Christmas Bird Count and national parks across the country are joining in. This annual census gives Audubon, the National Park Service, and conservation-based organizations important data about the status of bird populations and ecosystems. The event also makes for a great day outdoors, and birders and non-birders alike are flocking to parks and other designated locations to participate.

Whether you are hoping to glimpse a specific bird or aid a worthwhile cause, the NPS Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division (NSNSD) encourages you to take to the field and make your observations count. In preparing, consider that the sounds of birds often aid in sightings. Focus your ears as well as eyes. In the darkness of dawn, it may be difficult to spot an owl, but hearing its hoot will give clues about its location and identity.

"Birds like the canyon wren with its small stature and rusty brown body can blend into the landscape but their call is easily heard over great distances echoing off canyon walls at Lake Mead,” said Ashley Pipkin, an NPS acoustic biologist at Lake Mead National Recreation Area. "Listening can be an easy way to check many birds off your Christmas Bird Count List!"

Birds and Habitat

Bird calls and songs are among the diverse natural sounds that contribute to the richness of an outdoor soundscape. These sounds, like their makers, are vitally linked to the ecosystems they inhabit. Take the hummingbird, for example. With tell-tale whirring of wings and high chirps, the presence of hummingbirds indicates nearby flowers. Many plant species rely on hummingbirds for pollination and have evolved traits to attract them, such as sucrose-rich nectar and brightly colored flowers. To see flourishing blooms of columbines, lupines, honeysuckle and hollyhocks is to be in hummingbird habitat. From the sweet quaver of the Yellow-rumped Warbler found in North American woods and shrub terrain, to the ratchet honks of Sandhill Cranes heard at long ranges in the freshwater wetlands of the Mid-Southwest, to the tap-tap-tap of a woodpecker in wooded areas and forests, bird sounds reveal clues about their environment.

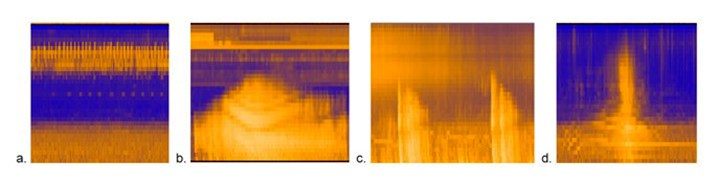

Declining bird species are often signs of degraded habitat, and vice versa. NPS scientists record and analyze sounds in parks to identify sound sources and understand what they reveal about the condition of park environments. Technicians study these sounds using spectrograms — images that display the sounds according to brightness and color, frequency, and time of occurrence (see graphic below). The frequency for bird songs is higher than that of a jet, thunder, or vehicle, and will appear in a different frequency range on a spectrogram. In this way, they can be distinguished from other sounds. Specific species can be identified in some cases. Scientists also conduct on-site listening while monitoring in the field. Like birding, this involves quietly listening to and noting sounds heard in the environment.

The bird sounds you hear will strengthen conservation knowledge.

NPS

Birding By Ear: Getting Started

NPS / Ken Conger

Listen!

The first step to birding by ear is to notice bird calls and songs when your outdoors. Even if you can’t identify the birds by sound yet, you will grow familiar with voices of your neighborhood. Next time you take a walk around the block, focus on the sounds around you. Can you hear any birds? Do they all sound the same or can you differentiate between the sounds?

Find a count near you.

Joining a bird count can be a great introduction to birding. Other, more experienced birders and park rangers can share their birding knowledge and help you identify birds that you see or hear. Check to see if any parks near you have a count or birding event:

Know your birding basics.

Birding is a low-cost, rewarding activity that helps you connect with the natural world anytime and anywhere. Get started with these birding basics.

NPS/Albert Myran

Get to know your local birds.

Knowing which birds frequent your area can help tremendously with bird identification. Use a field guide or check out one of the many bird identification apps. The apps will often have recordings to help you get to know your local birds by ear.

Explore sound galleries.

Check out these two NPS sound galleries, which feature a variety of sounds heard in parks, including a dawn chorus of birds recorded near Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park: NPS Sound Gallery and Yellowstone Audio Postcards.

Enjoy the experience!

Birding can be an almost meditative experience. Tune in to all your senses. Even the rustle of leaves and twigs may provide clues to a bird’s whereabouts. Enjoy the experience!

Test Your Birding By Ear Skills

What's Making that Sound

Are you ready for a challenge? Test your skills by listening to the recordings of bird calls and trying to figure out what bird made them.