Last updated: January 30, 2025

Article

How the NPS is protecting groundwater for people and ecosystems

NPS/Michael Quinn

Picture this: you’re visiting a national park in a desert landscape, and you spend your day exploring by foot in the summer heat. After seeing the sites that you had bookmarked in your visitor guidebook, you’re ready to relax and rehydrate, so you go to the visitor center, find the water spigot, and turn it on. Instantly, you get a nice, cool refill of water in your bottle, and you find a shady spot to sip and sit for a bit before you get back to it.

National Park Service (NPS) staff have provided a comfortable experience for you to access drinking water in an arid part of the world where plants and animals have very limited amounts of water to survive. But the convenience of this refreshing water supply may hide just how much planning and research goes into making drinking water available to millions of park visitors and staff each year, and the extent to which those waters are connected to natural and cultural features and processes that attract people to national parks.

Across its more than 430 park units, the NPS manages countless streams, springs, wetlands, and other water resources. The core mission of the NPS is “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations” as stated in the Organic Act of 1916.

Specifically for water, fulfilling this mission means the NPS must maintain sustainable water supplies for natural resources, cultural resources, and human uses in park operations. Particularly in arid parks where rain is limited and groundwater often supports most human and ecological water needs, this can be a delicate balance and major challenge. These days, sustainable water supply challenges are magnified by climate change and increasing demands on existing water supplies.

So, what does it really take to make water available for human use in national parks, while also managing natural and cultural resources to be “unimpaired”?

To understand this, let’s dive into why groundwater is a critical resource for humans, plants, and animals.

NPS/Michael Quinn

What is groundwater and why is it an important resource to conserve?

Groundwater flows underground through cracks and pores in rocks and sediment that make up water storage systems known as aquifers. Groundwater represents about 30% of all freshwater on Earth. By comparison, about 69% of Earth’s freshwater is stored in glaciers and ice caps and the remaining 1% of freshwater is found in lakes, streams, swamps, permafrost, and the atmosphere.

Humans can access groundwater by drilling wells or visiting springs, where groundwater naturally flows out of the ground and can be accessed at the surface. Plants and animals access groundwater where it flows near or above the ground surface, commonly near springs, streams, and wetlands.

Throughout the NPS, groundwater supports lakes, streams, wetlands, estuaries, springs, geothermal features, and associated ecosystems, some of which visitors may be familiar with, such as Yellowstone’s famous geysers and hot springs. Ecosystems that rely on groundwater for sustained existence are known as groundwater-dependent ecosystems. For many streams and rivers, groundwater serves a particularly important role in supplying “baseflow.” Following rain events and annual snowmelt periods, this baseflow allows the river to continue flowing throughout the year. This process is particularly important in times of drought. At springs and wetlands, groundwater commonly provides year-round aquatic habitat for many types of plants and animals that cannot survive in drier areas.

Groundwater also commonly supports water supply systems that provide park visitors and staff water for drinking, cooking, cleaning, and protecting buildings from fires. Additionally, many NPS sites and processes of significant cultural importance depend on groundwater, such as irrigation of historic orchards in Manzanar National Historic Site and the groundwater-dependent anchialine pools in Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park that made settlement possible in West Hawai’i.

Humans tend to over-extract water from springs and aquifers in “tragedy of the commons” scenarios in which individuals or particular groups use groundwater to their own advantage at the expense of the common good (Poeter et al., 2020). Global groundwater extraction has increased more than fourfold in the last 50 years (Wood and Hyndman, 2018). Over-extraction of groundwater has been shown to be detrimental to groundwater-dependent ecosystems and their associated native or endangered species, as well as disadvantaged communities that are marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution.

Groundwater must be managed properly to maintain a sustainable source of water for people and groundwater-dependent ecosystems. Recent investments from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are helping the NPS evaluate and manage park groundwater sources to sustainably meet the water demands of park operations, visitation, and the natural environment, particularly in the face of climate change.

NPS/Tyler Gilkerson

Inflation Reduction Act supports research on climate vulnerability of groundwater

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), enacted in 2022, makes $210 million available to the NPS, providing a historic opportunity to address critical resilience, restoration, and environmental planning needs.

Many NPS water supplies are sensitive to climate change and other modern stressors such as aging infrastructure, population growth, and commercial development. However, few NPS water supplies and groundwater sources have been evaluated for these vulnerabilities, highlighting an opportune research gap.

Two IRA-funded projects are evaluating the impacts of climate change and other stressors on NPS water supplies and groundwater-dependent ecosystems. One project focuses on the implications for people, and another focuses on the implications for ecosystems.

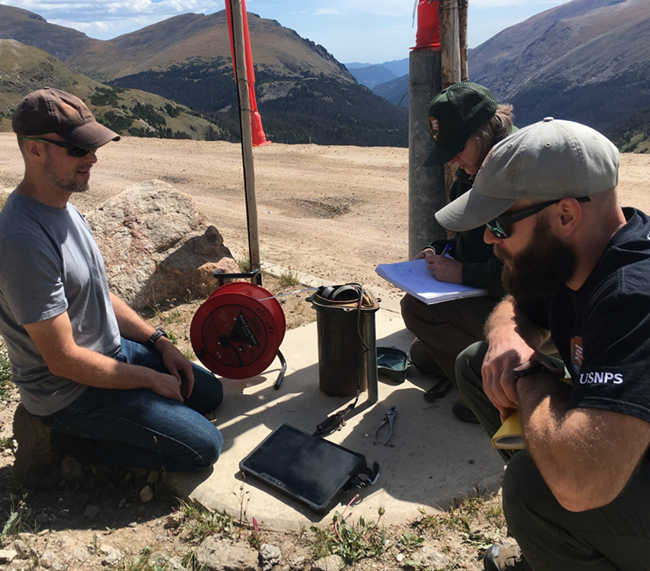

NPS/Derek Schook

Water for People

Staff of the NPS Water Resources Division (WRD) and the NPS Climate Change Response Program (CCRP) are leading the “Water for People” project in partnership with Colorado State University and the Department of the Interior's Office of the Solicitor. This project will kickstart water supply investigations, water right evaluations, and ultimately focus efforts on the most vulnerable water supply systems in the NPS. Such scientific and legal assessments will consider climate change effects, adaptation options, resource protection concerns, and water policy constraints for each park.

Specifically, this project will assess the climate change vulnerability of park water supplies to increase the security and sustainability of NPS water for people. Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments (CCVAs) and water right evaluations will be conducted for specific high-priority parks with significant water supply improvement needs and/or suspected vulnerabilities.

To conduct water supply-focused CCVAs, the project team compiles all existing information and data for a given water supply. They compare local hydrologic data against historical climate data to assess the sensitivity of these water sources to past changes in air temperature and precipitation.

Once a given water source's climate sensitivity is understood, a range of possible future climate conditions is used to project future changes in the adequacy of this water source. If a given water source is expected to become insufficient in the future due to a reduction in supply and/or an increase in demand, climate adaptation strategies are developed to mitigate the threat of future water shortages.

Some examples of these potential climate adaptation strategies for affected parks may include:

-

increasing water conservation measures

-

reducing leaks in water transmission lines

-

increasing water storage to withstand longer or more-intense droughts

-

switching to sources of water less vulnerable to climate change

The results of the analyses are communicated to parks to inform their resource management, operations planning, and investment decisions.

In addition, the Department of the Interior's Office of the Solicitor will compile information on existing NPS water rights, assess the vulnerability of NPS water rights to curtailment and legal challenges, and develop actionable legal strategies for adapting to climate change and enhancing water supply resilience.

NPS/Gilkerson

From 2023 to 2024, the project focused on evaluating the climate change vulnerability of water supplies at Bryce Canyon National Park and developing a NPS water supply database. Throughout 2024, the project will continue database development and assess climate change vulnerability of water supplies at Cedar Breaks National Monument, Zion National Park, and other park units.

"Our project team has chosen to pilot our water supply-focused CCVAs at [these parks] due to their diversity of water supply sources, abundant water supply data, major water infrastructure investment needs, and possible future climate conditions,” said Tyler Gilkerson, NPS hydrogeologist. “With over 6 million combined visitors per year and the threat of longer and more severe droughts, evaluating climate change vulnerability and adaptation options for these parks' water supplies is critical for ensuring that they are capable of meeting the demands of future generations.”

Thanks to this project, current and future generations of visitors will be able to continue accessing clean water supplies during their national park travels.

NPS/Steve Rice

Staff of the NPS WRD and the NPS CCRP are partnering with the University of Nevada-Reno Desert Research Institute (DRI) to lead the “Water for Ecosystems” project. Compared to “Water for People” which focuses on evaluating vulnerabilities facing human water supplies in national parks, this project focuses on protecting areas of natural groundwater discharge and their dependent ecosystems. The goal is to preserve these resources for current and future generations of visitors to enjoy.

Areas of natural groundwater discharge are often locations of backcountry water supplies, biodiversity hotspots, habitat for rare and endemic species, locations of cultural and spiritual importance, and sites of exceptional natural beauty. The NPS manages areas containing many of the few remaining unaltered or unimpacted spring sites in the country, particularly in the arid west.

The team will develop a geospatial database and web application for critical NPS groundwater-dependent ecosystems, evaluate their vulnerability to climate change, and identify restoration and adaptation opportunities, data gaps, and priority monitoring locations to address vulnerable ecosystems. The data will inform science-based decision-making for current and future maintenance of groundwater-dependent ecosystems in the NPS.

“Groundwater-dependent ecosystems are considered sentinel sites for evaluating the effects of drought and climate change on the broader landscape,” said Steve Rice, the NPS WRD Groundwater Program Lead. “Understanding where these features exist and how they have changed over time will allow for the development of tools and approaches to management, protection, and resilience.”

Additionally, with support from the Office of the Solicitor, this project will evaluate the vulnerability of NPS water rights and develop legal strategies for acquiring and protecting water rights to enhance the climate change resilience of groundwater-dependent ecosystems.

Through these projects, the NPS is stepping up to the challenge of increasing the security of park water resources that may be affected by climate change. These projects will have long-standing impacts for maintaining and protecting NPS water resources for current and future generations – and keeping you hydrated while you recreate, too.

References:

Eileen Poeter, Ying Fan, John Cherry, Warren Wood, Doug Mackay, 2020, Groundwater in our water cycle – getting to know Earth’s most important fresh water source. The Groundwater Project, Guelph, Ontario, Canada. https://doi.org/10.21083/978-1-7770541-1-3.

Environmental Justice, Justice 40 Initiative. (n.d.). The White House. Justice40 Initiative | Environmental Justice | The White House

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (n.d.). Wildfire-Climate Connection. https://www.noaa.gov/noaa-wildfire/wildfire-climate-connection#:~:text=Research%20shows%20that%20changes%20in,fuels%20during%20the%20fire%20season.

National Park Service. (n.d.). Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/climatechange/vulnerability.htm.

National Park Service. (n.d.). The Organic Act of 1916. https://www.nps.gov/grba/learn/management/organic-act-of-1916.htm.

U.S. Geological Survey. (n.d.). The Water Cycle. Water Science School. https://www.usgs.gov/special-topics/water-science-school/science/water-cycle.

Wood, W. W. and Dave Hyndman, 2018, Sea level rise cut in half?. Groundwater, volume 56, number 6, page 845, ngwa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gwat.12821.

Tags

- bryce canyon national park

- cedar breaks national monument

- zion national park

- ecosystem restoration

- climate resilience

- inflation reduction act

- bipartisan infrastructure law

- ecosystem

- visitor

- science

- cultural resources

- groundwater

- visitor experience

- justice40

- collaboration

- streams

- springs

- water

- water rights

- drinking water

- water resources

- climate change vulnerability assessments