In 1914, students braced against the chilly Idaho temperatures as they left their homes and traveled through the local farmland to the town of Rupert, where they filtered into their newly built “electric high school”—touted as a first in the nation. Inside, the temperature was a pleasant 68 degrees. Not only were the rooms warm, but electric lights glowed, and hot water flowed in the lavatories. In the “domestic science" rooms, girls exchanged winter coats for aprons and cooked on electric hot plates and ranges. Rupert Electrical High School even had a “good electric bell” connected to the principal’s office. All was made possible, The Salt Lake Tribune explained, by electric current flowing from “the Minidoka government dam” on the Snake River, 14 miles east of town.

Although the newspaper did not mention it, the power to heat Rupert’s schoolhouse came, not from the dam, but from its companion—the Minidoka Powerplant, originally built to provide electricity to pump irrigation water to desert lands on higher terraces along the Snake River. At each lift station, pumps lifted water approximately 30 feet from one segment of the main canal up to the next higher segment. On each terrace, the water then flowed by gravity through the irrigation system on that terrace.

Reclamation quickly realized that the new powerplant was capable of generating more electrical power than was used to operate the lift stations. As a result, Reclamation soon was delivering “excess power” to nearby towns and to rural homes on the Minidoka Project, where farm families sang the praise of Reclamation’s electricity. Not only was it cheap compared to coal, but electric radios and the glow from neighboring farms eased one’s feelings of isolation. Thus did Reclamation’s Minidoka Project make headlines as a pioneer in public power.

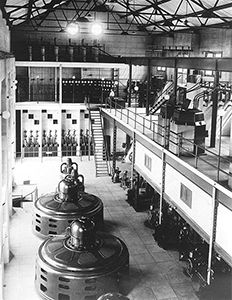

On May 9, 1909, Reclamation began operating the pumps at Lift Station #1, delivering water on a rental basis to about 3,600 acres on the south side of the Snake River. The charge for water was set at $1 an acre. Lake Walcott, the reservoir impounded behind Minidoka Dam, provided a fifty-foot head, or change in elevation, which powered the 7,000 kilowatt energy system in the powerplant. Penstocks—large pipes that carry water from the reservoir to the turbines—channeled water into the plant. Water plunged through the penstocks, then spun five 1,200 kilowatt vertically arranged Francis-type turbines, each connected to a 2,300-volt, alternating-current (AC) generator. Allis-Chalmers air-blast transformers, situated on a deck above the generator floor, stepped up the 2,300-volt current to 33,000 volts for transmission. As the water discharged into the Snake River, electric power surged through transmission wires to the lift stations. There, two substations stepped the incoming current down to 2,200 volts to operate the pumps.

In the fall of 1909, Reclamation negotiated power sales contracts with the project’s principal towns of Rupert, Heyburn, and Burley. Each signed contracts with Reclamation to purchase modest amounts of excess power from the government at “wholesale rates.” Reclamation built transmission lines to the towns and erected substations, where the voltage could be stepped-down for distribution. Initially, each town was guaranteed 1,500 kilowatts of power during the winter and 300 kilowatts during the summer, when most of the powerplant’s electricity was needed for irrigation.

Although the legislation that created the Reclamation Service never mentioned electricity, Reclamation’s ability to sell excess power came from the 1906 Town Sites & Power Development Act, which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to lease power generated on Reclamation projects and use the revenue as a credit to help repay construction costs. (The Reclamation Act of 1902 required that those who benefited from Federal irrigation water had to repay the construction costs.)

By the fall of 1910, Reclamation was delivering power to Rupert and the other towns, its sales getting a big boost from Barry Dibble, the project’s power superintendent, who embarked on a local lecture circuit to educate rural residents on the advantages of electrical heating over coal. At a time when marketing electricity for heating was almost unheard of, Dibble recognized that electric heat was perfect for a project like Minidoka, where electricity for pumping was not needed in the winter.

Dibble’s efforts paid off as local residents embraced the possibilities of this year-round electric power, hoping it would draw industries like beet factories and flour mills, increase settlement, and lighten housework at an affordable $1 per kilowatt. Since it was uneconomical for Reclamation to build transmission lines to serve farmsteads, beginning in 1913, at the bureau’s urging, local rural residents formed electric cooperatives, which contracted with Reclamation for electricity and then the cooperatives built transmission lines to carry electricity to outlying farms. In 1914, Rupert built its electrically heated school, followed in 1916 by another electric school in Burley. By 1920, at least 1,100 farm families—or 46 percent on the Minidoka Project—had access to electricity at a time when only 3 percent of other rural Americans did. Minidoka Project residents plugged in more than six thousand appliances, including electric irons, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and stovetop ranges.

In addition to its contracts with the towns of Burley, Rupert, and Heyburn, Reclamation also arranged power sales with the Amalgamated Sugar Company plant at Burley, as well as with a number of small villages in the region. Although the Minidoka story was a triumph for Reclamation, the accomplishment soon was surpassed at other projects—notably the Salt River Project in Arizona, which achieved 100 percent electrification on its 7,000 farms by 1929. The success of these rural power programs was later used as an example to obtain support for passage, in 1936, of the Rural Electrification Act.

Despite being an early prototype of Reclamation’s power program, success had not come easily on the Minidoka Project. In the first years of the project, farmers found profits hard to come by, and expenses ate up what profits there were, including payments owed to the government for building the dam and powerplant, as well as the project’s transmission lines and many canals and laterals. Many settlers, fearing loss of their land as they fell delinquent in their payments, agitated for change in the repayment rules, and formed water users associations to voice their concerns. In 1913, the Minidoka Irrigation District was established, which encompassed all of the lands irrigated by the gravity canal on both sides of the Snake River. Settlers on south-side lands that depended on pumped water soon followed with an irrigation district of their own, the Burley Irrigation District.

In 1913, the Minidoka Irrigation District, thinking it could lower costs, petitioned to take over from Reclamation the operation and maintenance of the Gravity Unit, and its request was approved in 1916, the first contract of its kind for Reclamation. Settlers on the more complex Pumping Unit lands were not so eager to take over operations, though they did so following requirements stipulated by the 1924 Fact Finders Act, which reorganized the U.S. Reclamation Service, including giving it a new name: the Bureau of Reclamation. Under the 1924 Act, power profits went to the water users, through their irrigation districts, to be credited toward repayment of project construction, operation and maintenance, and finally, as the water users directed.

Power shortages plagued the project even though Reclamation, early on, increased the capacity of the lift stations and, in 1927, added a sixth generating unit. These shortages weren’t resolved until a seventh unit was added in 1942. Also, for a time in the 1930s and 1940s, winter power production was shut down to conserve irrigation water during drought years.

It wasn’t until 1962, when Reclamation bought out the power rights of the two irrigation districts, that the federal government re-acquired rights to power system profits on the Minidoka Project. In 1963, as the Minidoka Powerplant was integrated into other federal hydroelectric power operations, the marketing of Minidoka power was transferred to the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), the entity created after World War II to market federal power in the entire Pacific Northwest.

In the early 1990s, work began on a new powerplant at Minidoka, with Units 8 and 9 added in 1997. Reclamation retired the original five generators from service but preserved them as museum pieces in the original powerhouse building. The four operational units have a combined total 27,700 kilowatt capacity. Since the project’s conception in the first years of the twentieth century, the Minidoka “Electric Project” not only transformed the landscape of the Snake River Valley, but also the Bureau of Reclamation itself as it found itself, however incidentally, in the electric power business.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017