Last updated: November 1, 2022

Article

Loons without lakes

Amy Larsen, Melanie J. Flamme, David K. Swanson, Sarah C. Swanson

NPS/Stacia Backensto

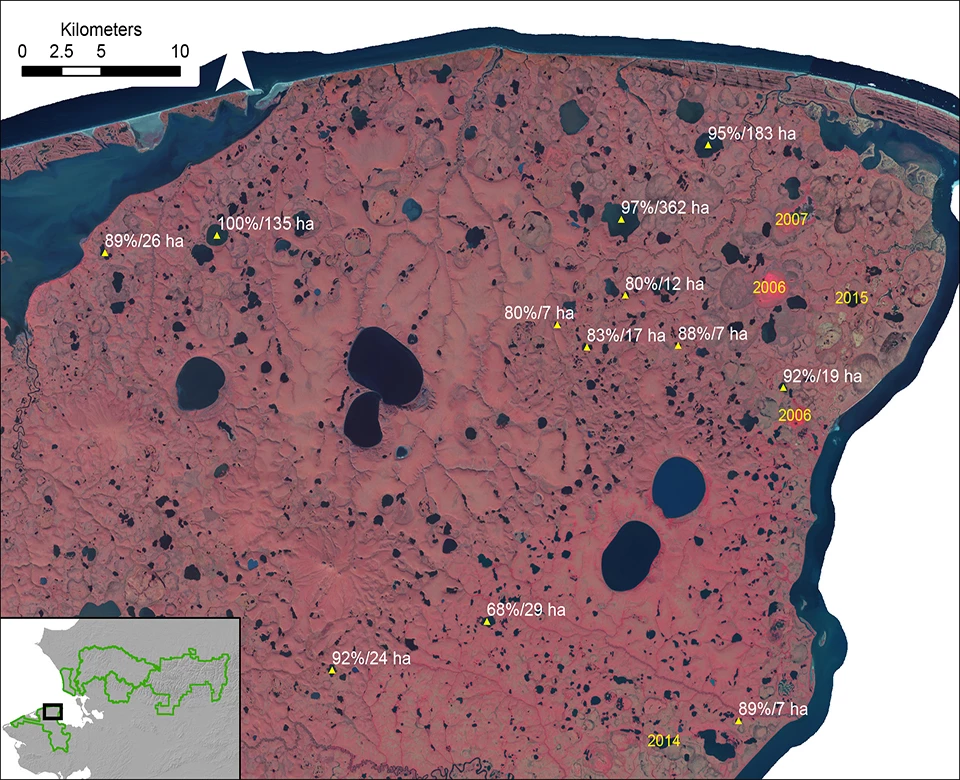

While flying loon surveys in Bering Land Bridge National Preserve in 2018, biologists witnessed widespread drying of coastal lakes, the likely consequences of a warming climate. Six sizeable lakes used by Yellow-billed, Pacific and Red-throated Loons drained rapidly (Figures 1a and 1b). Left behind were barren mudflats bereft of loons; gone were the fish, invertebrates and vegetation that provide cover and nourishment to the birds while nesting and chick-rearing. Bering Land Bridge NP is one of a handful of regions throughout the Circumarctic that contain lakes suitable for Yellow-billed Loons. Scientists were surprised by the large number, size and close proximity of the drained lakes, and were left wondering if this was an unusual event, and whether it would impact loon populations in the area.

Left image

Figure 1a. A large lake where Yellow-billed Loons nest in Bering Land Bridge National Preserve in June 2009.

Credit: NPS/Melanie Flamme

Right image

Figure 1b. The same lake in September 2018 catastrophically drained sometime between late June and early September.

Credit: NPS/Sarah Swanson

NPS/David Swanson

NPS/Jared Hughey

As top predators in lake ecosystems, Yellow-billed Loons are sentinels, acting as early indicators of ecological changes that Alaskan wildlife are likely to see in the coming years as climate warming continues. So far, the Yellow-billed Loon population in Bering Land Bridge NP appears relatively stable (Schmidt et al. 2014). Will that trend hold in the future? How will loons cope with the widespread draining of lakes? We will continue monitoring lakes and loons to better understand these rapid changes occurring in the Arctic.

For more information contact melanie_flamme@nps.gov

Earnst, S. L., R. Platte and L. Bond. 2006. A landscape-scale model of Yellow-billed Loon (Gavia adamsii) habitat preferences in northern Alaska. Hydrobiologia 567: 227-236.

Federal Register. 2014. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-month Finding on a Petition to List the Yellow-billed Loon as Threatened or Endangered. 50 CFR Part 17, Federal Register Vol. 79, No. 190/59195-59204.

Haynes, T. B., J. A. Schmutz, M. S. Lindberg, K. G. Wright, B. D. Uher-Koch, and A. E. Rosenberger 2014b. Occupancy of Yellow-billed and Pacific Loons: Evidence for interspecific competition and habitat mediated co-occurrence. Journal of Avian Biology. doi:10.1111/jav.00394

Schmidt, J. H., M. J. Flamme, and J. Walker. 2014. Habitat use and population status of Yellow-billed and Pacific Loons in western Alaska, USA. The Condor, 116(3):483-492. http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1650/CONDOR-14-28.1

Schmutz, J. A., K. G. Wright, C. R. DeSorbo, J. S. Fair, D. C. Evers, B. D. Uher-Koch, and D. M. Mulcahy. 2014. Size and retention of breeding territories of Yellow-billed Loons in Alaska and Canada. Waterbirds. doi:10.1675/063.037.sp108

Tags

- bering land bridge national preserve

- arctic

- loons

- arctic network

- bering land bridge national park service

- inventory and monitoring division

- yellow-billed loons

- lakes

- lake drying

- science

- arctic science

- cape krusenstern national monument

- birds

- national park service

- permafrost thaw

- arcn

- permafrost

- loon

- lake

- natural resource

- alaska

- wildlife