Last updated: June 26, 2023

Article

Martin Van Buren's "Return to the Soil" (Teaching with Historic Places)

National Park Service

Ex-President Van Buren returned to the place of his nativity on Saturday last...after the lapse of a long series of years, spent in the service of his country, he has returned to the home of his youth, probably to spend the evening of his days among those who have long appreciated the splendor of his genius and admired his virtues.

--Kinderhook Sentinel, May 1841

Upon the end of his presidential term in 1841, Martin Van Buren did indeed move to his recently purchased estate, located only two miles away from the small New York village of Kinderhook, where he was born and raised. At this estate, which he called Lindenwald, the skillful politician, loyal successor to President Andrew Jackson, and eighth president of the United States (1837-1841) spent his retirement years.

Restored to the period of his occupancy (1841-62), Lindenwald reflects the refined sense of fashion and the comfortable way of life of a sophisticate. It is the home of a small town boy who ultimately rose to the presidency and who, along the way, acquired a taste for the finer things in life. In decorating his home, he spared no expense. Fifty-one elaborate imported wallpaper panels formed a mural-like hunting scene in the hall. Fine furniture and Brussels carpets added to the elegance. The estate also provides evidence that the man had not forgotten his origins. He was comfortable living as a well-to-do farmer in the Kinderhook region where he was born.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file “Lindenwald” (with photographs) and other sources related to Van Buren. It was written by John Miller, a former Park Ranger at Martin Van Buren National Historic Site. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Time Period: Early to mid 19th century

Topics: This lesson complements classroom study of early 19th-century politics by tracing the life of Martin Van Buren and examining his retirement home. It could be used in U.S. history courses and in civics or government classes. Students will gain a deeper understanding of the man who played an important role in the Jacksonian Era.

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Martin Van Buren's "Return to the Soil" relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

- Standard 1C: The student understands the ideology of Manifest Destiny, the nation's expansion to the Northwest, and the Mexican-American War.

- Standard 2A: The student understands how the factory system and the transportation and market revolutions shaped regional patterns of economic development.

- Standard 3A: The student understands the changing character of American political life in "the age of the common man."

-

Standard 3B: The student understands how the debates over slavery influenced politics and sectionalism.

Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

- Standard 1A: The student understands how the North and South differed and how politics and ideologies led to the Civil War.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Martin Van Buren's "Return to the Soil" relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

- Standard B: The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

- Standard E: The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

- Standard F: The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

- Standard A: The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.

- Standard D: The student identifies and analyzes examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and group or institutional efforts to promote social conformity.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard B: The student describes the purpose of government and how its powers are acquired, used, and justified.

- Standard C: The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet needs and wants of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

- Standard E: The student identifies and describes the basic features of the political systems in the United States, and identifies representative leaders from various levels and branches of government.

- Standard F: The student explains conditions, actions, and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among nations.

- Standard H: The student explains and applies concepts such as power, role, status, justice, and influence to the examination of persistent issues and social problems.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

- Standard D: The student describes a range of examples of the various institutions that make up economic systems such as households, business firms, banks, government agencies, labor unions, and corporations.

- Standard I: The student uses economic concepts to help explain historical and current developments and issues in local, national, or global contexts.

Theme X: Civic Ideals, and Practices

- Standard C: The student locates, accesses, analyzes, organizes, and applies information about selected public issues - recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

- Standard D: The student practices forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic. •

- Standard F: The student identifies and explains the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

- Standard J: The student examines strategies designed to strengthen the "common good," which consider a range of options for citizen action.

Objectives for students

1. To describe Van Buren's character as reflected in his lifestyle;

2. To explain Van Buren's political views and his role the Jacksonian Era;

3. To understand national issues of the 1830s and positions taken by political parties;

4. To identify ways in which political campaigns act as expressions of popular culture;

5. To compare Van Buren's attitude toward the depression of 1837 with Herbert Hoover's stance toward the Great Depression of the 1930s;

6. To study a recent campaign in their area.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can either be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students.

1. Two maps of the Hudson River Valley region;

2. Three readings about Van Buren's private and political life;

3. Photos and drawings of Lindenwald;

4. A political cartoon.

Visiting the site

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, administered by the National Park Service, is just south of Kinderhook, New York, on Highway 9H. The house is open daily May through October. For more information, write the Superintendent, Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, P.O. Box 545, Kinderhook, NY 12106 or visit the park web pages.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Library of Congress

What might this cartoon be depicting? Of the two men, which one does the artist give more importance to? What makes you think so?

Setting the Stage

Martin Van Buren (1782-1862), the eighth president of the United States, was called the "Sly Fox" and the "Little Magician" because he was a clever and beguiling politician, proficient at manipulation, persuasion, party organization, and compromise. His political career spanned three decades.

Early 19th-century politics was characterized by boisterous personalities, opposing interest groups, and ill-defined political parties. In the 1824 presidential election, all four candidates claimed the DemocraticRepublicans as their party. Van Buren, then a U.S. senator, believed it was time for the renewal of the two-party system. By the 1828 election, Andrew Jackson, supported by Van Buren, was running under what would soon be called the Democratic party. The opposing party was known as the National Republicans.

Van Buren was a friend, trusted adviser, and vice president to Andrew Jackson during the latter’s second term in office (1833-37). When he became president in 1837, Van Buren’s own administration continued the policies of the new Democratic party established under “Old Hickory.” The principles espoused by the young party, which Van Buren helped form, included states’ rights, limited powers of federal government, and strict constitutional construction. The opposing party, the Whigs (formerly the National Republicans), were united by their disdain for Jacksonian policy and their approval of active government programs.

As soon as Van Buren took office, he faced a serious financial panic and depression. True to Jacksonian laissez-faire philosophy, Van Buren called for the creation of an independent treasury system that would separate the federal government from the banking system. The Independent Treasury Bill, passed in 1840, had no real impact on the economy, however. Furthermore, it alienated many of Van Buren’s fellow Democrats.

In the 1840 election, Van Buren ran against the Whig candidate, William Henry Harrison, hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe. Rather than establishing a strong political platform, the Whigs ran a “hurrah” campaign in which they used symbolism and slogans to rally the people behind Harrison and against Van Buren. The image of Harrison in a log cabin sipping cider convinced voters that he was a man of the people. By contrast, the Whigs depicted Van Buren as an aristocrat living in high style in the White House while people were suffering from the depression. The enthusiasm for “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” coupled with the country’s severe economic crisis, made it impossible for Van Buren to win a second term.

Locating the Site

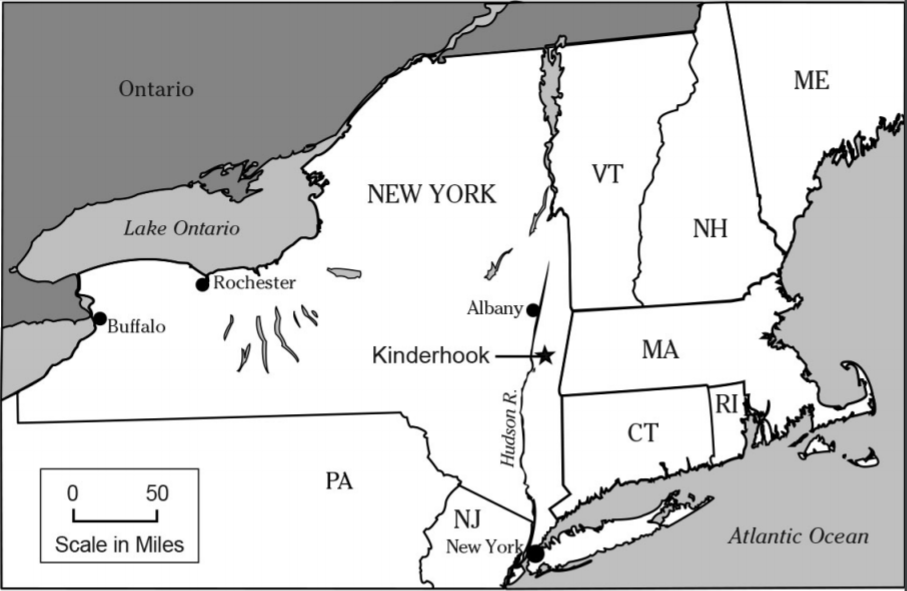

Map 1: New York and Surrounding States

National Park Service

Kinderhook, New York marks the location where Martin Van Buren spent his youth as well as his retirement. During Van Buren's lifetime the Albany or Old Post Road was the main thoroughfare between New York City and Albany. This road passed through the Old Dutch settlement of Kinderhook ("children's corner") where Van Buren's parents owned a tavern. A gathering place for local residents, the tavern also welcomed travelers bound for Albany & New York City.

Questions for Map 1

1) Locate Kinderhook and note its location between Albany and New York City.

2) As a child growing up in Kinderhook, what types of people might Martin Van Buren have come in contact with as they made their way to New York or Albany?

Locating the Site

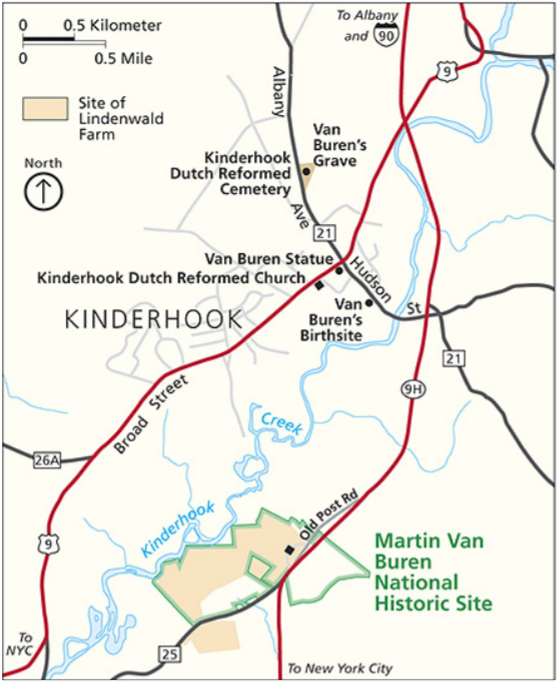

Map 2: Kinderhook, New York

National Park Service

Questions for Map 2

1) Locate the site of the tavern where Van Buren was born in 1782.

2) Use the map scale to determine the distances between Martin Van Buren National Historic Site (Van Buren's retirement estate), the site of his birth, and the Kinderhook Cemetery where he is buried. What does the relationship between these sites suggest about Van Buren's affection for the area?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Life of Martin Van Buren

Born in December 1782, Martin Van Buren grew up in the small community of Kinderhook, New York. He came from a large family that was the fifth generation of descendants of Dutch immigrants who settled in New Netherland in the early 1600s. Almost everyone in Kinderhook was related. Most spoke Dutch with their fellow townspeople and English with outsiders.

Abraham and Maria Hoes Van Buren owned a tavern that was a favorite meeting place in the town. The Van Burens never became wealthy, but neither were they poor. Young "Matty" did his share of work in the tavern and spent much time listening to well-dressed, important men discuss business and politics over their drinks. He attended Kinderhook Academy, where all students of the community went. Most students of Van Buren's social and economic status dropped out after a couple of years to help their parents, but he stayed on as long as he could, even though he knew he could never afford to go to college as his wealthier classmates would. By age 14, having excelled in English and Latin, Van Buren left school to study law under a local attorney.

During the next several years Van Buren became intensely interested in politics. By the time he was 20, he had impressed the popular and important Van Ness family so much that he was offered a job in New York City at William Van Ness's law office. This experience provided Van Buren with more than training in the law. He also became acquainted with national politics and politicians, including Vice President Aaron Burr.

After Van Buren passed the bar exam, he returned to Kinderhook and went into business with his stepbrother. He quickly built up an important practice and became well known throughout the state. In 1807 he married Hannah Hoes with whom he would have five sons. In 1808 the newlyweds moved to Hudson, the county seat and a somewhat larger town than Kinderhook. Van Buren immediately became involved in politics and backed the successful Democratic-Republican (generally shortened to Democratic) candidate for governor. For his efforts he was appointed to a county post, which kept his name in front of the public. He also continued his law practice, which involved considerable travel around the state.

In 1812 Van Buren won an election to the state Senate and immediately gained a reputation as a War Hawk. The War Hawks were a group of young politicians, mostly from southern and western states, who called for war against Great Britain. That was a fairly unpopular position for a northerner to take because Great Britain was the major trading partner of the developing industries of the northern states. It was also unpopular early in the war when the British were handily outfighting the Americans. When the Battle of Lake Champlain ended in American victory, however, Van Buren's stance became the popular one, and his fame spread to the national level.

Although he won many friends while he served New York, he also made enemies when he organized his own supporters and practiced patronage in an unprecedented manner. Patronage was the power to make appointments to government jobs, especially for political advantage. His circle of politicians, known as the Albany Regency, is regarded by many historians as the first "political machine" in American politics. It easily brought about Van Buren's 1821 election to the U.S. Senate.

In Washington, D.C., Van Buren continued his wheeling-and-dealing brand of politics, and by 1828 he had helped to ensure Andrew Jackson's election to the presidency. He himself had run for and been elected governor of New York, which he resigned after only four months to become Jackson's secretary of state. He soon resigned that post to take the position of minister to Great Britain. The Senate refused to confirm his appointment, however, because both he and his mentor, Andrew Jackson, had many enemies among the senators. In 1832 Van Buren was selected as Andrew Jackson's running mate.

Van Buren was elected to the presidency in 1836 as the true heir to the popular Jackson. Utilizing restraint and levelheaded action, Van Buren resolved two potentially dangerous incidents on the Canadian border, thus avoiding confrontations with Great Britain. He resisted arguments for the annexation of Texas because he believed that it would aggravate the sectional antagonism between North and South, and risk a war with Mexico. His position was unpopular, even though it was prophetic.

Van Buren's long, skyrocketing career reached its zenith with the presidency and quickly began its decline. The nation was caught up in a depression that began in 1837, and as president, Van Buren was blamed. In the election of 1840, he was badly beaten by William Henry Harrison. He looked homeward toward Kinderhook and the estate he had recently purchased. He would never again hold public office. He did try for the Democratic nomination in 1844 but could not draw votes from the South, because of his stand against the annexation of Texas. In 1848 he was willing to head the Free Soil ticket, even though he knew he had little chance to win the presidency. Nevertheless, his name on that ticket helped the antislavery movement, as he knew it would. Although he was an intensely political man and committed to the virtues of compromise, he never departed from his deepest convictions: the Jeffersonian ideals of limited federal power and a strict interpretation of the Constitution.

Ever in the shadow of Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren never quite achieved his own niche in American history. Even at his presidential inauguration, he was upstaged by Old Hickory. The crowd wildly cheered Jackson that day while giving Van Buren only polite applause. "For once," commented Senator Thomas Hart Benton, "the rising sun was eclipsed by the setting." But perhaps this is only as it should be for a politician who preferred the antechamber to the orator's podium. As a founder of the Democratic party, Van Buren was an organization man--everything for party, the individual was secondary.

Van Buren was the first of the second generation of American politicians. The fact that he had been born in 1782, the year after Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, held a special significance for him; he was the first president to have American citizenship at his birth.

Perhaps Andrew Jackson gave the best tribute to Martin Van Buren. Jackson once commented that he was aware that Van Buren was referred to as the "Little Magician." Jackson confessed that he believed the nickname to be appropriate enough, but that the "magician's" only wand was "good common sense."

Reading 1 was compiled and adapted from the National Park Service visitor's guide for Martin Van Buren National Historic Site; Rafaela Ellis, Martin Van Buren (Ada, Okla.: Garret Educational Corporation, 1989); and John P. Platt, "Historic Resource Study, Lindenwald: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, New York," National Park Service, 1982.

Questions for Reading 1

1) What kind of education did Martin Van Buren receive?

2) How did Van Buren's job at Van Ness's law office advance his career in politics?

3) What reputation did Van Buren gain through his involvement in politics? What political positions did he hold prior to becoming president?

4) Why do you think Van Buren was "ever in the shadow of Andrew Jackson"?

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Martin Van Buren as Compromiser

In the days of President Jackson, a Washington establishment known as Jess Brown's Indian Queen Hotel was a favored meeting place of members of Congress and other influential men of the government. If a man sought to express his political convictions, it was there he could readily find an audience and, inevitably, an argument. One April evening, the Indian Queen was the stage for a confrontation that foretold the division of the Republic.

In 1830 a traditional Democratic banquet celebrating the birthday of Thomas Jefferson progressed in a predictable manner until the time came for the offering of toasts. The gathering gradually hushed itself and looked expectantly toward the tall, severe form of its chief. President Andrew Jackson had sat straight and silent throughout the evening. He was in a dark temper because his quarrel with Vice President John C. Calhoun over the tariff and the right of states to nullify federal laws had turned ugly. Those who knew him anticipated a storm. Now the president rose and gazed upon the attentive gentlemen who overfilled the tobacco-sullied hall. He lifted his glass. His fierce eyes now sought those of his vice president. He offered not a toast, but rather a command: "Our Union — it must be preserved!"

Stricken by the force of the challenge, Calhoun's face was drained of its color. All that he represented had been unexpectedly challenged. The "cast iron man" stiffened, recovered and lifted his own glass. "Our Union," Calhoun replied, "next to our liberty, most dear! May we always remember that it can only be preserved by distributing equally the benefits and the burdens of the Union."

The abiding question was expressed in the clash of those contradictory toasts: federal union vs. state sovereignty, the one vs. the many. Which should prevail? In time, hundreds of thousands of Americans would die, over that question as it applied to slavery. Yet on this pleasant spring evening the specters of war were still only shadows. There was still time for compromise.

A third toast was given that night; it went unheeded and was all but forgotten. Yet the voice of moderation and reconciliation was also present at that dinner party. The third toast, offered by a polished, rotund little Dutchman from the Hudson River Valley, came while the tension of the exchange between Jackson and Calhoun was still in the air. Secretary of State Martin Van Buren drew himself erect and proclaimed: "Mutual forbearance and reciprocal concessions. Through their agency our Union was founded. The patriotic spirit from which they emanated will forever sustain it."

Mutual forbearance. Reciprocal concessions. Compromise had always served Van Buren well. Its skillful employment had generated his spiraling career and culminated in his rise to the presidency. It was said that he "rowed to his objectives with muffled oars." Fellow politicians often claimed that he was evasive and noncommittal. A story that may be untrue, but which appears in nearly every biography of Van Buren, claims that an acquaintance once asked in jest if Van Buren thought the sun rose in the east. "I have heard that that is the common belief," Van Buren told him, "however, I do not arise before dawn, so I could not say with any certainty." When tested however, Van Buren held true to his own beliefs even when they were unpopular.

Reading 2 was compiled from John Niven, Martin Van Buren: Romantic Age of Politics (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983); and Robert V. Remini, Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959).

Questions for Reading 2

1) What issues brought about the conflict between President Jackson and Vice President John C. Calhoun?

2) What was meant by Jackson's toast? What was the meaning of Calhoun's rejoinder? How did those two positions foreshadow the Civil War?

3) What did Van Buren mean by his toast?

4) Early in Van Buren's career, the noun "noncommittalism" was used to criticize him. What evidence in the reading suggests that this might have been an accurate accusation?

5) What might be some of the advantages of compromise? Are there times when compromise is not an acceptable solution?

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Home at Last

In 1797 Peter Van Ness, Revolutionary War veteran and a local public figure, built the mansion in which Martin Van Buren was one day to dwell. Van Ness's son, William, inherited the property in 1804 and retained it for 20 years, after which it was purchased at auction by William Paulding, Jr. It was from this owner that Van Buren acquired the estate in 1839.

Soundly defeated in his quest for reelection to the presidency in 1840 by William Henry Harrison, Van Buren remained confident as he made his way homeward to Kinderhook. In four years' time, he was certain, the "sober second thought of the people" would return him to the presidency. Although he had not intended to retire to the estate so soon after purchasing it, his interest in the political storms of the old days began to subside once he was there.

Two of Van Buren's heroes--Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson--as well as other previous presidents, had retired to the life of a gentleman farmer. Van Buren had visited Monticello and the Hermitage, the plantations of Jefferson and Jackson, and he may have felt that living in such a house and pursuing the occupation of farmer was the appropriate way for an ex-president to spend his retirement.

He set about making his piece of the Hudson Valley into a productive farm as well as a fashionable estate. By 1845 he could gaze proudly on more than 220 acres of cropland, as well as formal gardens, ornamental fish ponds, wooded paths, and outbuildings of all kinds. In the main house, he removed the central stairway to create larger rooms on both the first and second floors--an idea he borrowed from Jefferson's remodeling of Monticello. From France he ordered 51 vividly colored wallpaper panels that formed a mural-like hunting scene in the downstairs hall. He also put in an indoor bathroom. Along with his fine new furniture and Brussels carpets, he embellished the house with portraits of some personal friends--Henry Clay and Andrew Jackson.

In 1849 Van Buren invited his son Smith Thompson and his family to move into the house with him. Smith Thompson was to help manage the estate and was allowed to make alterations to better accommodate his growing family. He quickly hired one of the best-known architects of the time, Richard Upjohn, who had won his fame designing churches. The architect added more pipes for running water, and many rooms, but made even more alterations to the exterior of the house. Upjohn changed the exterior appearance from an 18th-century Georgian house to a mid-19th-century Italianate-style villa. A four-story brick tower, a central gable, attic dormers, and a new front porch soon appeared. When Smith Thompson had the house painted yellow, the neighbors wondered if Van Buren would tolerate such an extreme alteration. The indulgent father was not at all upset: "The idea of seeing in life the changes which my heir would be sure to make after I am gone amuses me."

Van Buren lived happily at Lindenwald until his death in 1862. In a letter to an old friend he wrote: "The evening of my life is passing far more quietly and agreeably than I could have hoped." On July 24, 1862, as General Robert E. Lee prepared to invade the North, the man who had fought to defuse the sectional tensions between North and South, and who had succeeded in forming a national party of disparate factions, died at Lindenwald. His last words: "There is but one reliance." His tombstone stands unobtrusively among those of his family, friends, and neighbors at rest in Kinderhook Cemetery. It is a simple obelisk, its inscription fading away with the passing of years.

Reading 3 was compiled from the National Park Service visitor's guide for Martin Van Buren National Historic Site; Bill Harris, Homes of the Presidents (New York: Crescent Books, 1987); John Niven, Martin Van Buren: Romantic Age of American Politics (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983); and John P. Platt, "Historic Resource Study, Lindenwald: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, New York," National Park Service, 1982.

Questions for Reading 3

1) Why would it have seemed appropriate to Van Buren to retire to a farm with a great house?

2) How did he modify the house and grounds at Lindenwald?

3) What changes were made after Smith Thompson and his family moved in with Van Buren? How did Van Buren respond to those changes?

4) How does Van Buren's gravestone reflect his personality?

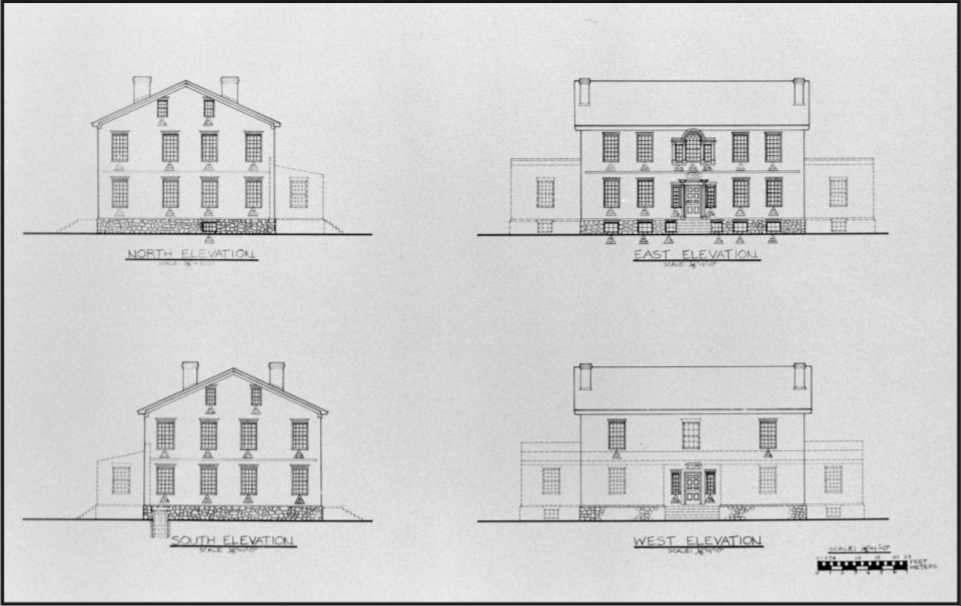

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site

In 1797, Peter Van Ness hired local builders and used native materials in the construction of his large, two-and-one-half story, red brick house.

Questions for Drawing 1

1) How would you describe this house?

2) Why would it be important to know the appearance of this house prior to Van Buren's occupancy? How do you think we know what the house looked like when it was first built?

Visual Evidence

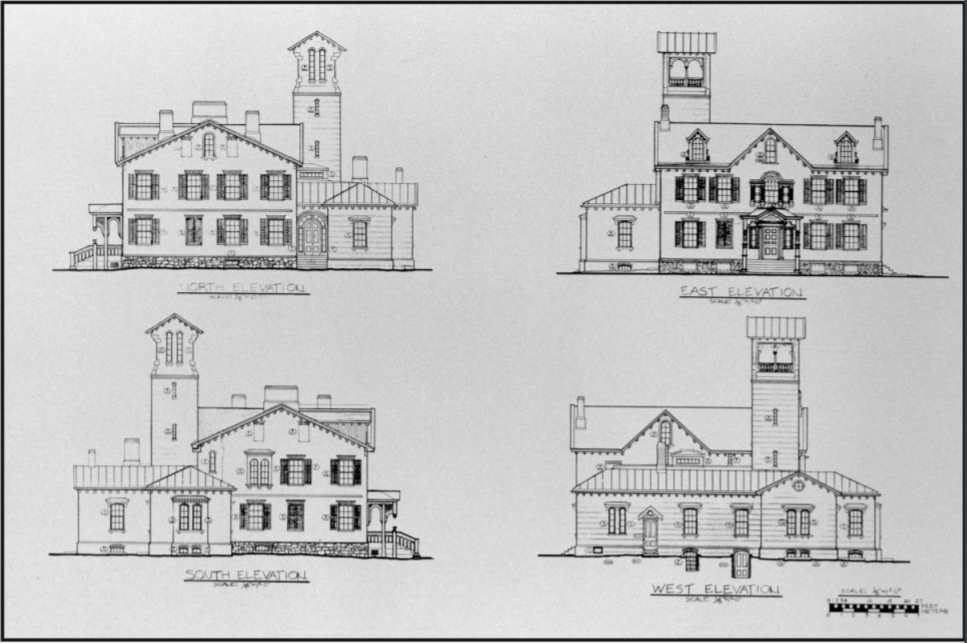

Drawing 2: Elevations of Lindenwald in 1862

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Lindenwald Today

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site

Peter Van Ness's house was in a state of neglect when Van Buren purchased it in 1839. Although Van Buren began improvements immediately, it was not until his son hired the prominent architect Richard Upjohn in 1849 that the house took on its present appearance.

Questions for Drawing 2 and Photo 1

1) Compare the appearance of the house in Drawing 2 and Photo 1 to that in Drawing 1. What major changes were made to Lindenwald between 1797 and 1862?

2) Why might Van Buren's son have chosen to alter the appearance of the house so dramatically? What do his and his father's improvements indicate about the family's financial status?

Visual Evidence

Photo 2: Entrance Hall, Lindenwald

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site

This photo shows the imported French wallpaper panels mentioned in Reading 3. The paper was very costly, and it immediately showed visitors the owner's good taste to appreciate French designs, which were considered the best in the world.

Questions for Photo 2

1) What types of scenes are depicted in the wallpaper?

2) Van Buren used this pattern in his home after seeing a similar paper at Andrew Jackson's estate, the Hermitage. What does this suggest about the way the two men related to each other?

Visual Evidence

Cartoon 1: Depiction of Van Buren Taking the Blame for His Own and Jackson’s Monetary Policies

Library of Congress

This caricature is typical of political cartoons of the time. It illustrates Van Buren's short stature — "Little Magician" — and clearly shows that he was always in the shadow of the popular Andrew Jackson.

Questions for Cartoon 1

1) How does the cartoon make fun of Jackson's battle with the Bank of the United States and Van Buren's Independent Treasury Act?

2) What is the point of view of the person who drew the cartoon?

3) What building appears in the background and why?

Putting It All Together

Van Buren was part of a great change that took place in American politics during the 1830s and 1840s. Party conventions became institutionalized in the election of 1832, when Andrew Jackson was nominated by the Democrats, the party that succeeded the Democratic-Republicans. In 1834 Jackson’s political opponents formed a new party called the Whigs. The following activities will help students become more familiar with that era of history.

Activity 1: Democrats and Whigs

Divide the class into two groups and assign each one to study either the Democrats or the Whigs. Ask each group to use American history textbooks and other sources to research the activities of the party they have been assigned. They should concentrate on the 1830s and try to answer the following questions: How did the party stand on issues such as slavery, states’ rights, and tariffs? What slogans or campaign songs did they develop? What candidate did they choose for the election of 1840? What promises did their presidential candidate make? Students may create posters, digital displays, or oral presentations to communicate their answers to the class.

Activity 2: Comparing Presidents

Both Van Buren and Herbert Hoover lost their opportunity for a second term when they were blamed for depressions that were not solely their fault. Have students research the financial panic and depression of 1837 and compare it with the Great Depression that began in 1929. Have them compare the positions of Van Buren and Hoover on the role of government in ending a depression. Facilitate students’ thinking by reading aloud the following: (1) When questioned as to why he did not do more to alleviate suffering during the depression of 1837, Van Buren replied, "It is not the objective of government to make men rich—nor repair their losses"; (2) Hoover claimed that federal aid would cause "degeneration of that independence and initiation which are the very foundation of democracy." Then ask students to write short papers in which they discuss the current accepted responsibility of the president and the federal government for the economic welfare of the nation.

Activity 3: Political Cartoons

Have students make a collection of current political cartoons from newspapers and news magazines. Review several of the more biting political cartoons and ask students to decide if they believe exposure to ridicule and criticism is fair or unfair. Ask them how much influence they think such cartoons have on the general public. Do they find visual criticisms (cartoons) more effective than editorials? What part do they think humor ought to play in politics? To what degree do they believe political cartoons reflect the issues? Do they encourage or distract valid debate?

Activity 4: Local Political Campaigns

Ask the class as a whole to choose a recent or current local political race to investigate. Divide the class into two groups and have each group choose one of the candidates and gather information on his/her campaign. Groups should address the following issues in their investigations: office being sought, major campaign issues, slogans, nicknames of candidates, use of advertisements, propaganda, local media coverage of the campaign and election, and results of the election. After students have gathered their information, ask a spokesperson from each group to present their findings to the class. Hold a classroom discussion comparing the two campaigns. Ask students for whom they would vote and why. Find out if students became biased in favor of the candidate they researched. Why or why not? Next discuss some similarities and differences between these modern local campaigns and national campaigns of the 1830s.

Additional Resources

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site

The Martin Van Buren National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park System. The park's web pages include a virtual tour of Lindenwald, links to recent research including an article on domestic servants at Lindenwald, and images of artifacts and documents in the site's museum collection.

American Presidents Travel Itinerary

The Discover Our Shared Heritage online travel itinerary on American Presidents provides information about the 8th President of the United States, Martin Van Buren, and the home where he retired, the Martin Van Buren National Historic Site.

Biographies of Martin Van Buren

The following include:

- a copy of Martin Van Buren's Inaugural Address;

- a portrait from the White House.

National Archives (NARA)

The Archives has placed on its web site a large number of items about Martin Van Buren and his presidency. To find them, visit the NARA search engine.

Kinderhook Connection

Kinderhook Connection details the history of the area Martin Van Buren called home.