“War is declared. We shall have another dash at our old enemies.” —American Commodore John Rodgers to his crew aboard the frigate President.

Library of Congress

The United States’ earliest war aims centered upon the conquest of Canada. For that reason, and because Britain’s navy was so overwhelmingly dominant on the high seas, influential members of Congress favored appropriations for the Army instead of money for the Navy. An army could be created quickly, and relatively cheaply; building naval vessels was extremely expensive and could take years.

President Madison was inclined to agree with the members of Congress who favored the army, believing the American navy too small to challenge the mighty British. Instead, key members of the cabinet promoted privateering as the most cost-efficient means of antagonizing the British at sea. Even the Secretary of the Navy, Paul Hamilton, wanted to preserve the roughly twenty-ship American naval fleet by keeping it in port.

Most naval leaders agreed that the U.S. could not defeat the British Navy outright. But some naval commanders believed that America’s navy, while small by great-power standards, was still of excellent quality. Those leaders argued that the American navy could take advantage of the Royal Navy’s preoccupation with France and harass British merchant shipping. Employing America’s modest navy in such a fashion, they held, might persuade the British to reconcile with the Americans in order to concentrate on the greater struggle with Napoleon.

Commodore John Rodgers made a case for this aggressive war on commerce. Rodgers advocated deploying American ships in larger groups, called squadrons, to force the British to scatter their ships to safeguard merchant shipping. Squadron actions would thus draw British ships away from the American coastline. One of Rodgers’ fellow officers, Commodore Stephen Decatur, endorsed the tactics of raiding, though he suggested that American ships be deployed singly or in pairs, relying on the individual initiative, skill, and daring of navy officers.

During the war, the Americans employed a blend of naval tactics and techniques in their war against the Royal Navy. Privateers proved effective, taking upwards of 500 prizes a year. But even those successes could not turn the tide of the war, since they represented less than 3% of the British merchant fleet.

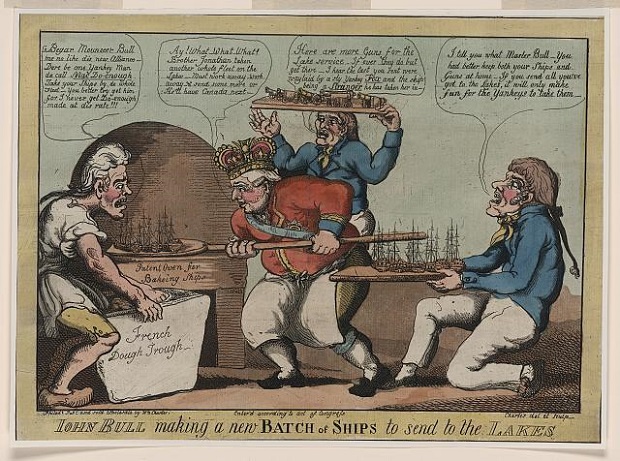

Naval victories on the Great Lakes and at Lake Champlain were much more important in shaping the war’s outcome. Historians generally label those successes as critical, since they preserved the prewar status of the northern borderlands. That provided the Americans important diplomatic leverage during the peace negotiations at Ghent. The Americans also won several dramatic victories over the Royal Navy on the high sea. While those triumphs boosted Americans’ confidence and embarrassed the British, they had less strategic impact on the war.

Perhaps the most significant legacy of the naval war was to burnish the image of the young U.S. Navy. Some of America’s most renowned wartime heroes were naval commanders, and post-war folklore emphasized their exploits. Stirring phrases like Oliver Hazard Perry’s message “We have met the enemy, and they are ours” and James Lawrence’s dying command “Don’t give up the ship” became an enduring and inspiring part of the U.S. Navy’s legacy.

By the end of the conflict the United States Navy had established a level of respectability abroad and credibility at home. That new reputation justified its existence in the mind of the public, and led to increased financial support for the Navy. Most telling was the fact that, in the wake of the war, Secretary of the Navy William Jones recommended expansion of the Navy, instead of the usual postwar cutbacks and mothballing.

Last updated: May 24, 2016