Last updated: January 14, 2021

Article

Connecting Fire History and Fire Management at Colorado National Monument

Think that pinyon-juniper forest “hasn’t burned in a thousand years”? You may be right. Vegetation research yields surprising results about fire intervals at Colorado National Monument.

Background

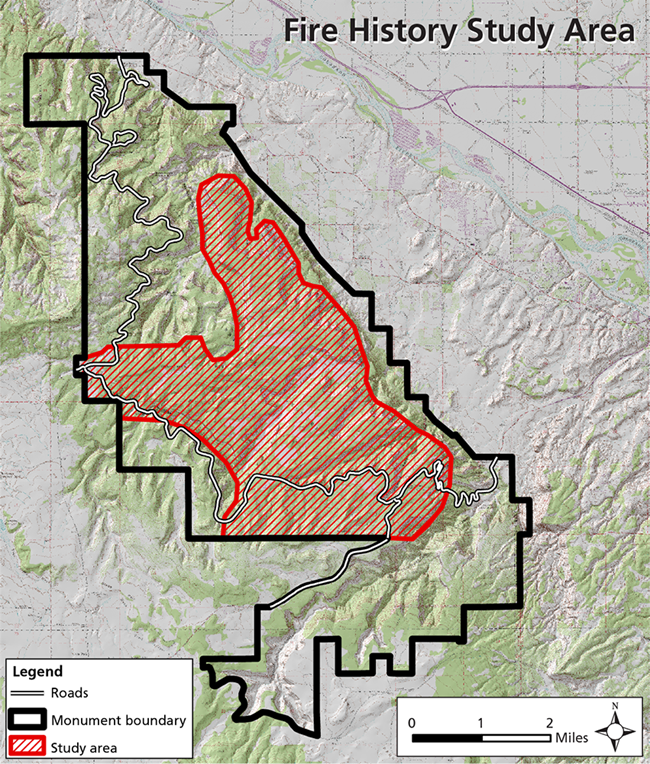

Colorado National Monument (NM), on the northeastern edge of the Uncompahgre Plateau, supports a persistent pinyon-juniper (Pinus edulis - Juniperus osteosperma) woodland that has not been disturbed by large, stand-replacing fires since modern fire recordkeeping began. In fact, when researchers from Colorado Mesa University examined fire history and woodland structure on over 1,600 hectares of the monument, they found no evidence of large, stand-replacing fires (e.g., charred wood or truncated stand structures) in the entire study area.

A great variety of pinyon-juniper community types cover roughly 40 million hectares of the western United States, each differing in structure, composition, and disturbance regimes. However, researchers have only recently begun to differentiate between the historical fire regimes of those individual types. Persistent pinyon-juniper woodland, unlike some other types, tends to favor geological and geographical conditions that do not support frequent fires. Research on these woodlands across the Colorado Plateau has revealed natural fire rotations ranging from approximately 300 to more than 600 years.

Variations like these make it clear that successful resource management planning requires detailed knowledge of a park’s baseline conditions and specific ecological context. At Colorado National Monument, researchers set out to (1) estimate when the last large (>100 ha) stand-replacing fire occurred, (2) characterize and compare the population structures of pinyon pine and juniper, and (3) document levels of cumulative mortality.

Results

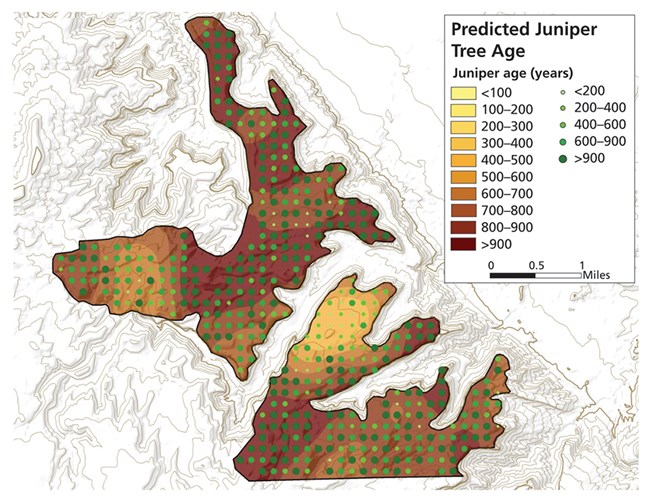

Multiple lines of evidence indicated that large, stand-replacing fires have been absent from the study area (see map) for time periods approaching a millennium. For example, junipers estimated to be >900 years old were found at 44% of sampling points (see figure, next page). In addition, when 11 charcoal layers, sampled from the major canyon draining the easternmost boundary of the study area, were dated with 14C techniques, the most recent date of fire shown was 1,180 YBP (years before present). Although the last fire may not have been quite that long ago (if, for instance, that most recent charcoal sample came from pinyon pines or junipers that were already several centuries old at the time of the fire), the average interval between the 11 charcoal dates was 790 years, which still points to very long fire-free intervals. A third source of evidence is the lack of charred wood in the study area. Research from this region suggests that dead pinyon pine or juniper wood on the ground persists for as long as 1,100 years; 600-year-old dead wood is relatively common.

The rarity of large, landscape-scale fires at Colorado NM is not likely due to a lack of ignitions. In the 67 years since the park started keeping records, there have been, on average, 1.5 small fires recorded each year. What is striking is that none of these ignitions has resulted in a large fire over such a long time period.

Instead, differences in weather, topography, and fuels may explain why the park has a longer fire rotation than nearby pinyon-juniper woodlands, where large fires have occurred in recent years. Colorado NM is often on the leeward side of major weather systems that generally move from the southwest/west to the northeast/east. Topographical fuel breaks may also play a role. Most of the study area is isolated by sheer cliffs (150+ m high) that act as islands or peninsulas of fuel. A more discontinuous canopy may also contribute to the longer fire-free intervals.

Differences in surface fuels also likely play a role in the contrasting fire frequencies of areas within and outside the park. Burned areas outside park boundaries have experienced significantly more livestock grazing than the study site. It would be fruitful to investigate whether the grazed areas correlate with higher cover of invasive species (such as cheatgrass [Bromus tectorum], providing a contiguous layer of fine surface fuels more conducive to fire spread), as well as to study the abundance of cheatgrass in those burned areas prior to the fires, which can be accomplished by analyzing remote sensing imagery taken before the fires occurred.

Invasive plant monitoring by the Northern Colorado Plateau Network has revealed that the lowest frequency of invasive plant species occurs on the mesa tops, while the canyon bottoms have the highest frequency. This is consistent with the history of grazing in the park, which was mostly limited to the canyon bottoms. It will be important to continue to monitor cheatgrass and control this and other invasive species to prevent the spread of future fires through these non-native fuel components.

Management Implications

A significant finding of this study is that the park’s fire rotation may be longer, and the woodlands older, than other persistent pinyon-juniper woodlands documented in the Colorado Plateau, meaning that fire regimes in Colorado NM were likely not significantly altered by 20th-century fire suppression. Therefore, rather than needing the reintroduction of fire or mechanical treatments to restore stand structure, these systems may represent rare examples of communities still within their historical range of variation. As such, prescribed underburns or mechanical thinning of these forests would not represent ecological restoration and in fact, could do long-term damage by removing old-growth trees and opening up sites for invasion by introduced species.

Furthermore, due to their long fire-free intervals, these persistent woodlands offer a rare look at how long-term influences, such as climatic variability or disturbances other than fire, can influence woodland structure and development. The current spatial pattern of stand structure at the park represents what old-growth woodlands can attain in the absence of large, intense disturbances. These structures reflect a relatively uniformly distributed juniper population, but a more spatially variable distribution of pinyon that may reflect the patchy nature of more frequent (relative to juniper) recruitment and mortality episodes.

This study also provides important baseline data for changes that may be brought about by climate change in coming decades. As many ecologists have noted, we may be witnessing a period in which vegetation patterns are being shifted over large areas in a short period of time. With the expected increase in drought conditions in the Southwest, we may see a sharp decline in the pinyon component of many pinyon-juniper woodlands. If climate change brings weather conditions more conducive to wind-driven fire, or if cheatgrass and other invasive species that create contiguous fine surface fuels continue to spread, we may lose large areas of pinyon pine and juniper and the communities they support. Invasive species control (particularly of cheatgrass), which could increase the resilience of pinyon-juniper woodlands to fire, is one aspect of this system that is potentially within management control.

For more information, see the full report: Kennard, D., and A. Moore. 2012. Fire history, woodland structure, and mortality in a piñon-juniper woodland in the Colorado National Monument. Final report to National Park Service.