Article

On the March to Fort Wagner

Upon reading the text of President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts moved swiftly to turn part of this proclamation into reality: raising an all Black regiment to fight in the U.S. Civil War. The Proclamation declared all people enslaved in lands held by the Confederates to be free, but also authorized Black men to be enlisted into the armed services for the United States. Governor Andrew secured permission from the War Department to form the 54th Massachusetts (54th MA) Regiment, which became the first federally recognized Black regiment from the North to fight in the Civil War. The 54th MA initially filled with men from in and around Boston, but others from all over the world soon joined, including Robert John Simmons.

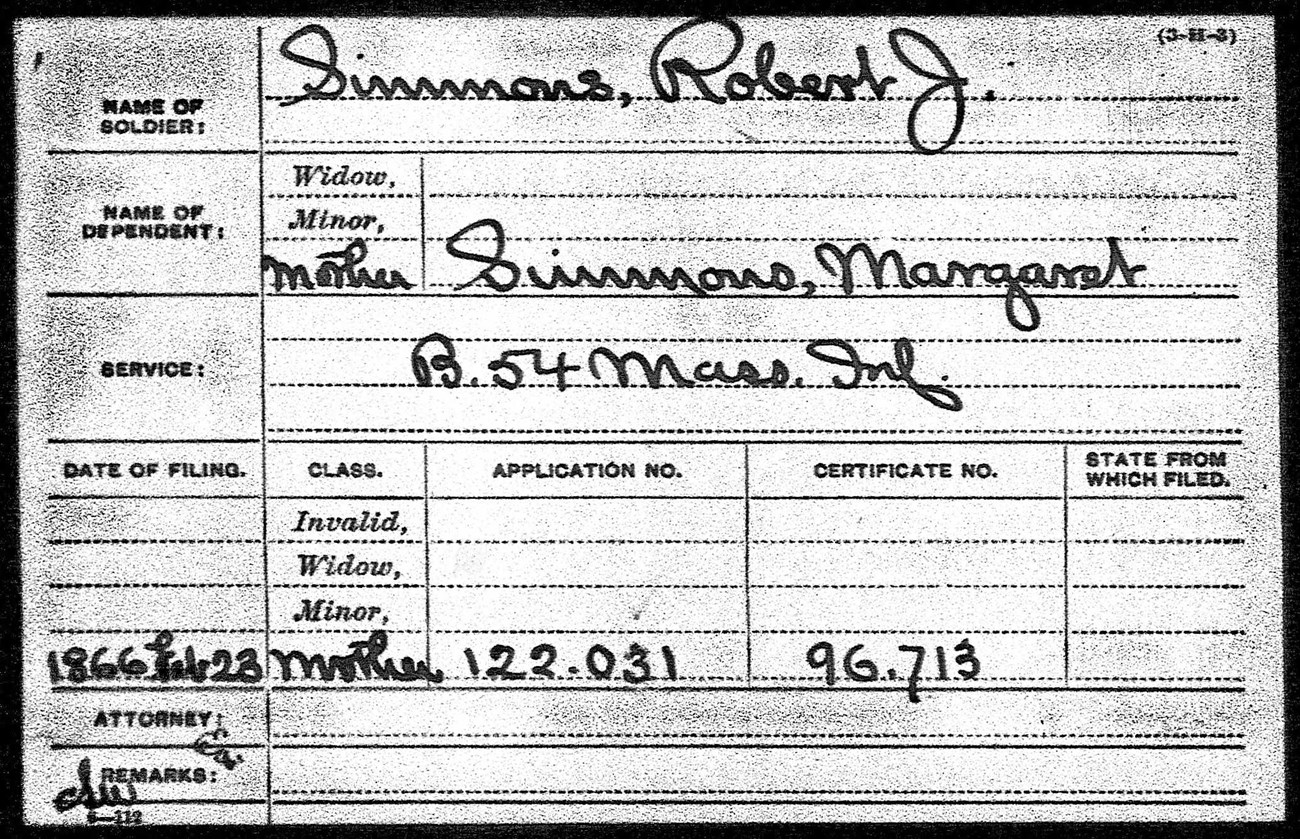

The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Record Group Title: Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 1773 - 2007; RG #: 15; Series Title: U.S., Civil War Pension Index: General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934; Series #: T288.

Born in Bermuda around 1837 to Joseph and Margaret, Robert enlisted as a Private in the 54th. Abolitionist William Wells Brown, author of The Negro in the American Rebellion, considered Simmons an impressive individual, calling him "a young man of more than ordinary ability." Wells Brown also introduced Simmons to Francis George Shaw, father of Robert Gould Shaw, who thought that Simmons "would make a valuable soldier."1

Listed as a clerk in his previous job, Simmons soon earned a promotion to the rank of 1st Sergeant. Simmons' clear handwriting likely played a factor in his promotion. Reporting to Camp Meigs in Readville, Massachusetts, Simmons would drill with the 54th MA and then traveled to South Carolina with the rest of the men in anticipation for battle.2

We do not know what motivated Simmons to enlist, but many soldiers did so to support their families financially. Simmons had no children of his own, but his sister Susan Reed had two children living in New York with his mother, Margaret. As Simmons prepared to take part in his first battle in July 1863, little did he know his family in New York had to fight for their own survival. Tensions had been rising in New York City for weeks after Congress passed the Enrollment Act, which established the first draft in the United States. The Act required most men between the ages of 20 and 45 to register for the military and exempted African Americans from the draft. Poorer, working, and middle-class men, new citizens, and immigrants felt they bore the brunt of this new law as a provision of the Act allowed wealthy men to enroll substitutes for $300 (adjusted for inflation would be over $7000 today). Though the first draft pull went smoothly on the 11th of July, two days later emotions exploded on the streets of Manhattan for the second draft pull.3

During the morning of July 13, hundreds of New Yorkers spilled into the streets and began attacking people and buildings. They targeted government buildings, homes, and Black New Yorkers. Margaret took the two children out of the house, hoping to get to safety, while Susan Reed went to return laundered clothing to clients so it would not get stolen or destroyed. Unfortunately, Joseph Reed, the eldest, became separated from her and the crowd soon began to savagely beat him. A firefighter attempted to break through the crowd to save the 7-year-old but could not help in time. Joseph Reed died of his wounds on July 14, 1863.4

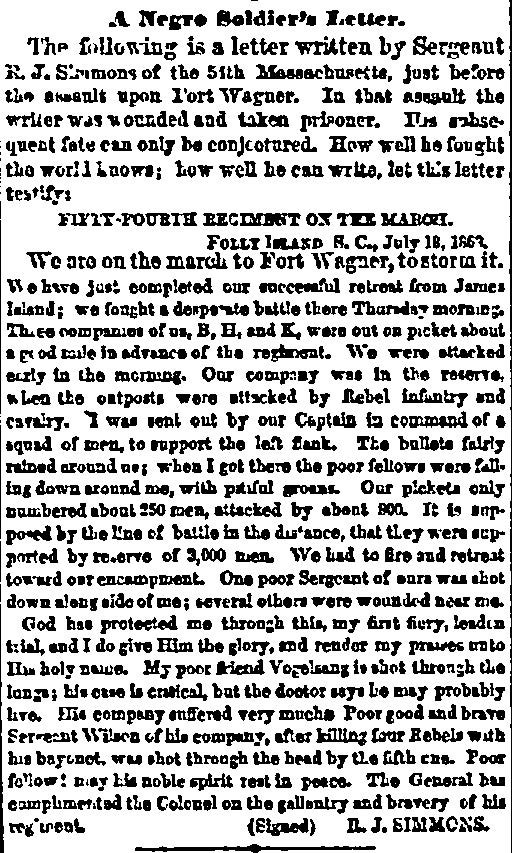

Four days later, Robert Simmons sat down and penned a letter without knowing any of this. We do not know the letter’s intended recipient. Simmons wrote, "We are on the march to Fort Wagner, to storm it. We have just completed our successful retreat from James Island." He described his experience in his first battle, "The bullets fairly rained around us; when I got there the poor fellows were falling down around me, with painful groans." While many sustained injuries, including his friend 1st Lieutenant Peter Vogelsang, Simmons escaped unharmed.5

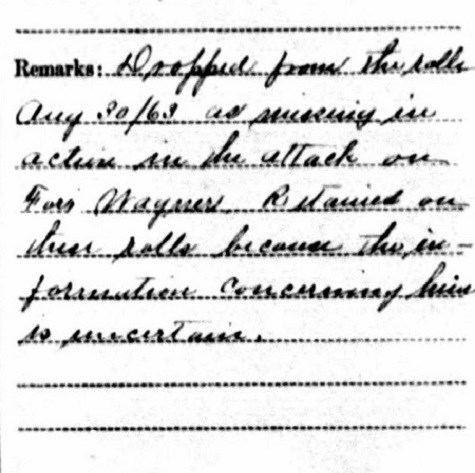

Unfortunately, Simmons' luck did not continue. He and the rest of Company B fell into formation as the Second Battle of Fort Wagner began on July 18, 1863. By the end of the attack, Simmons sustained wounds and became a prisoner. Simmons suffered for at least a month before dying in a Charleston, South Carolina jail in August of 1863. Though only with the 54th MA for a short time, Simmons made a strong impression. Captain Luis Emilio wrote in Brave, Black Regiment that,

First Sergeant Simmons of Company B was the finest-looking soldier in the Fifty-fourth, a brave man and of good education. He was wounded and captured. Taken to Charleston, his bearing impressed even his captors.6

For the next few months, Robert Simmons' records read, "Absent: missing since the assault on Fort Wagner, July 18, 1863." Others suffered the same fate as Simmons in places like Charleston Jail, the Florence Stockage, and Andersonville. Some died of their wounds with their bodies placed in mass graves with no markers. Others such as Isaac Hawkins, survived their time spent in these prisons in spite of hardships and punishments. A year after Robert's capture, Margaret Simmons filed for a survivor pension from the government.7 Despite receiving a promotion to 1st Sergeant, Robert Simmons sadly never received any pay before his capture and death. That same year, Susan Reed gave birth to another son and named him Robert John after her brother, carrying on his legacy.8

Contributed by: Jocelyn Gould, Park Guide

Footnotes

[1] William Wells Brown, The Negro in the American Rebellion: His Heroism and His Fidelity, Boston, MA: Lee & Shepard, 1867.

[2] The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the U.S. Colored Troops, 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (Colored); Microfilm Serial: M1898; Microfilm Roll: 15.

[3] Albon P. Mann, "Labor Competition and the New York Draft Riots of 1863," The Journal of Negro History 36, no. 4 (1951): 375-405. Accessed July 10, 2020.

[4] “Local Intelligence. To the Slain by the Rioters. Abraham Franklin. Augustus Stuart. Peter Heuston. James Robinson. William Jones. Wm. Henry Nichols James Costello. Mrs. Derickson. Joseph Reed. William Jackson Samuel Johnson.” The New York Times. September 20, 1863.

[5] RJ Simmons, "A Negro Soldier's Letter," New York Tribune, December 23, 1863. http://www.genealogybank.com (accessed July 8, 2020). [See full text of the letter below]

[6] Luis Fenollosa Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment: The History of the Fifty-fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865. New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1995.

[7] The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Record Group Title: Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 1773 - 2007; Record Group Number: 15; Series Title: U.S., Civil War Pension Index: General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934; Series Number: T288.

[8] Year: 1870; Census Place: New York Ward 8 District 11, New York, New York; Roll: M593_981; Page: 301B; Family History Library Film: 552480.

New York Tribune

Robert Simmons' Letter

The following is a letter written by Sergeant R.J. Simmons of the 54th Massachusetts, just before the assault upon Fort Wagner.

Fifty Fourth Regiment on the March

Folly Island S.C., July 18, 1863

We are on the march to Fort Wagner, to storm it. We have just completed our successful retreat from James Island; we fought a desperate battle there Thursday morning. Three companies of us, B, H, and K, were out on picket about a good mile in advance of the regiment. We were attacked early in the morning. Our company was in the reserve when the outposts were attacked by Rebel infantry and cavalry. I was sent out by our Captain in command of a squad of men, to support the left flank. The bullets fairly rained around us; when I got there the poor fellows were falling down around me, with painful groans. Our pickets only numbered about 250 men, attacked by about 800. It is supposed by the line of battle in the distance, that they were supported by reserve of 3,000 men. We had to fire and retreat toward our encampment. One poor Sergeant of ours was shot down along side of me; several others were wounded near me.

God has protected me through this, my first fiery, leaden trial, and I do give Him the glory, and render my praises unto His holy name. My poor friend Vogelsang is shot through the lungs; his case is critical, but the doctor says he may probably live. His company suffered very much. Poor good and brace Sergeant Wilson of his company, after killing four Rebels with his bayonet, was shot through the head by the fifth one. Poor fellow! may his noble spirit rest in peace. The General has complimented the Colonel on the gallantry and bravery of his retreat.

R.J. Simmons (Signed)

Tags

- boston national historical park

- boston african american national historic site

- 54th ma regiment

- 54th massachusetts

- 54th massachusetts regiment

- 54th mass

- boston

- boston african american national historic site

- boston national historical park

- african american history

- civil war history

- fort wagner

- service of the 54th

- 54th gallery