Last updated: April 24, 2025

Article

Paleontology and Geology of Big Bone Lick National Natural Landmark

Article by Justin Tweet, Paleontologist, NPS Geologic Resources Division

Photo courtesy of Big Bone Lick State Historic Site.

Mastodons, mammoths, and giant ground sloths are among the most familiar fossil mammals. Some of the first scientifically studied fossils of these Ice Age mammals came from a salt spring just east of the Ohio River in northern Kentucky, today about a half-hour drive southwest of Cincinnati. Here, for tens of thousands of years, salt has been dissolved from buried ancient marine bedrock and brought to the surface by groundwater, forming a natural salt lick that attracts large animals. Over those tens of thousands of years, great numbers of bones became preserved here, inspiring the name “Big Bone Lick”.

NPS photo by Vincent Santucci.

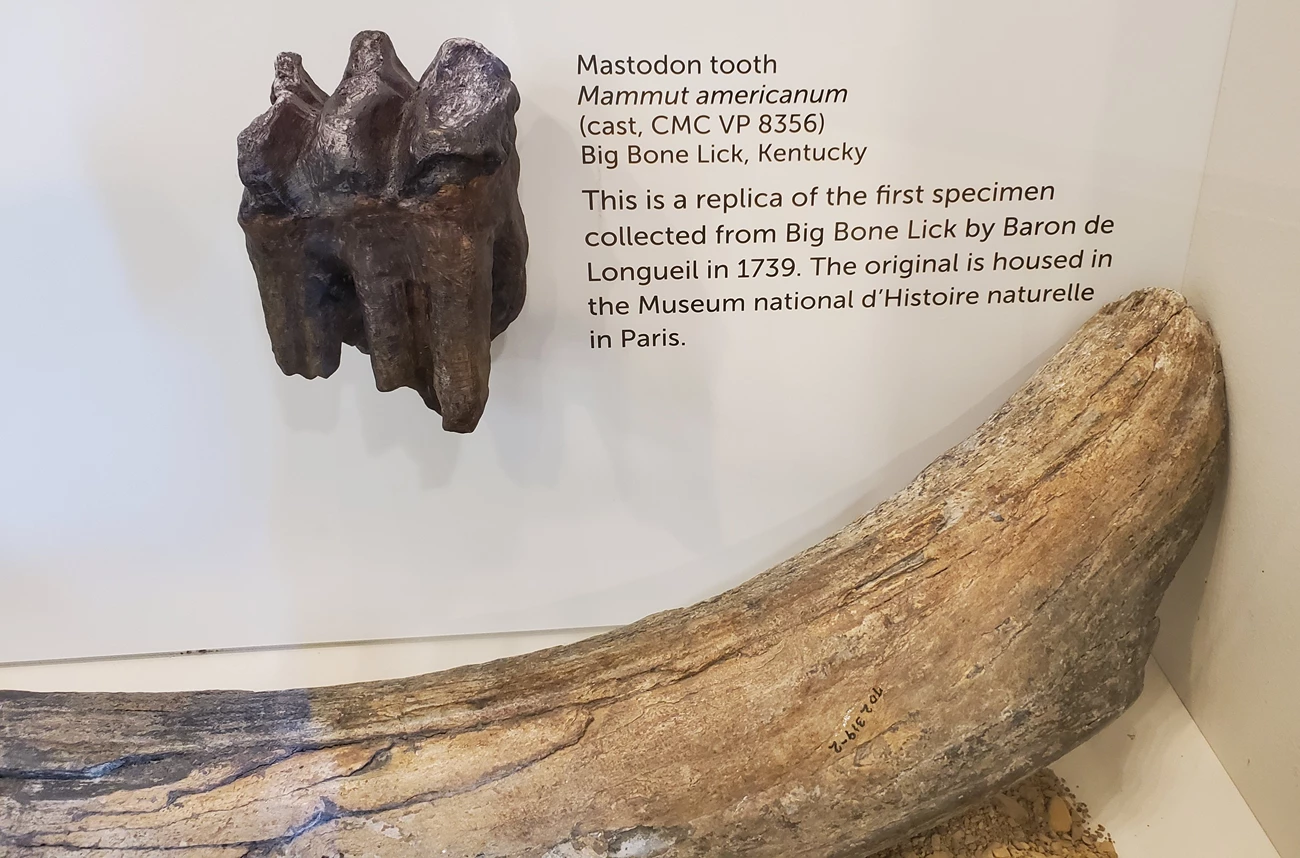

In 1739, Charles III le Moyne, the second Baron de Longueuil, was leading a military expedition from Montreal against British-allied Chickasaw who were threatening New Orleans and control of the Mississippi. His party, traveling down the Ohio River, stopped near the mineral spring. While there, allied native hunters brought back several fossil bones and teeth that the Baron took to France at the conclusion of the expedition. These were described and illustrated in the mid-1700s, and most of them are still at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in Paris (Tassy 2002).

NPS photo by Vincent Santucci.

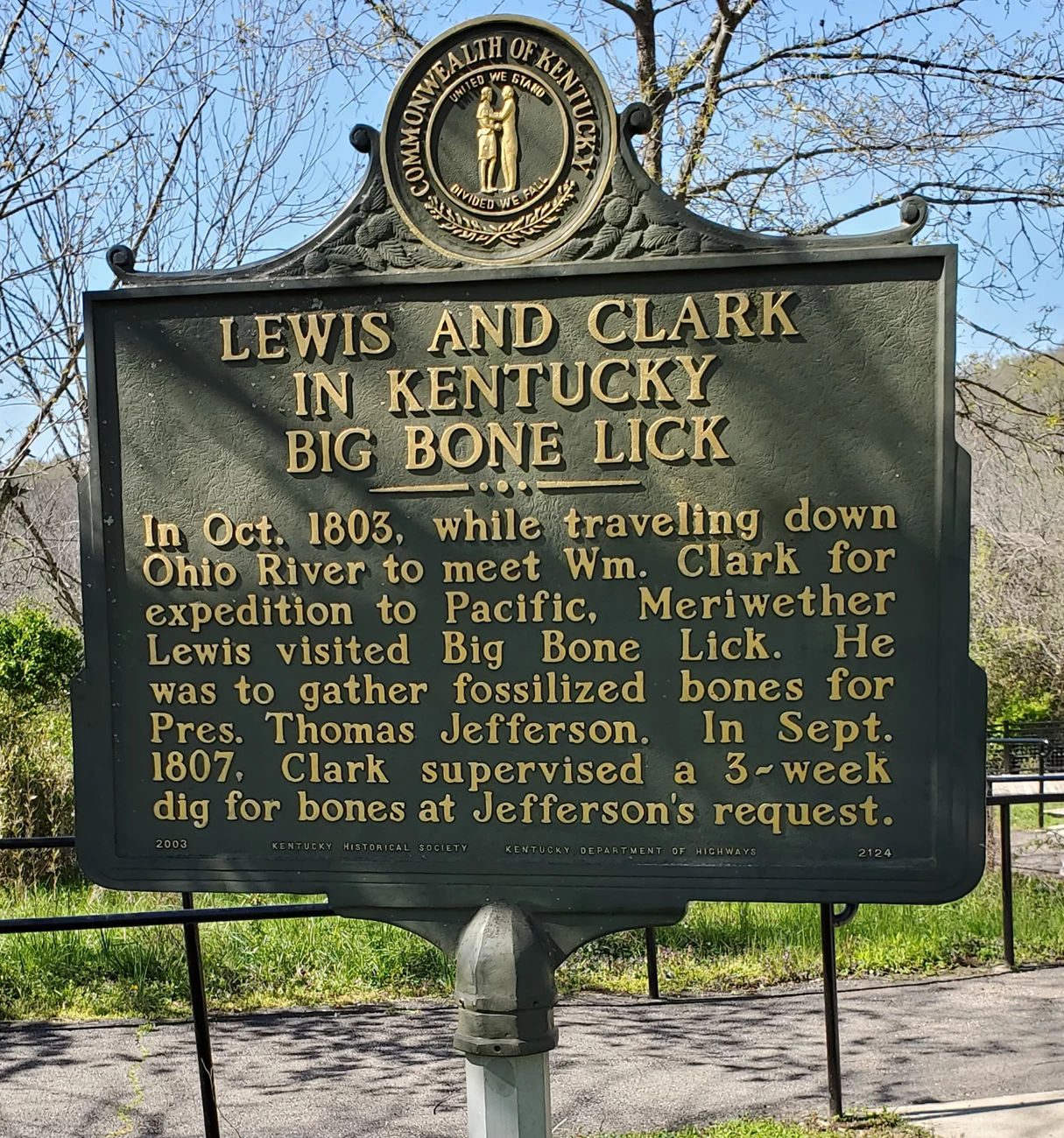

The finds at Big Bone Lick fired imaginations and stimulated scientific minds. From the 1750s to about 1868, when Nathaniel Southgate Shaler had all remaining easily accessible fossils removed for the Museum of Comparative Zoology of Harvard University, many parties visited and made collections, bringing specimens to Europe and the growing cities of eastern North America. Fossils collected there made their way to presidents and nobility, most famously Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, whose orders for the Lewis and Clark expedition included searching for animals like those represented by fossils from Big Bone Lick on their western expedition, decided to secure his own fossils from the site. In October 1803, on the way to join the expedition, Meriwether Lewis collected fossils from the site and sent them to Jefferson, but they were lost when the boat transporting them sank near Natchez, Mississippi. (Similar losses were not uncommon; for example, in 1795 future president William Henry Harrison collected 13 hogshead barrels’ worth of fossils from the site, but they too were lost with their boat.) In 1807 Jefferson commissioned William Clark to revisit the site. This time the bones arrived safely, and Jefferson exhibited some of the fossils in the White House. Some of the bones have been preserved to this day at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University and the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle. For Jefferson, the fossils were particularly important for establishing that “New World” animals were not “degenerate” in comparison to “Old World” animals.

NPS photo by Vincent Santucci.

For much of the early history of Big Bone Lick, paleontology was not even a defined branch of science. It would not come into its own until after the concept of extinction was formulated around 1800, a concept that Big Bone Lick fossils helped to inspire. One of the most significant fossil animals of Big Bone Lick is the elephant-like mastodon. Although most of its bones are very much like those of an elephant or mammoth, its teeth are much different: the chewing surface is something like an egg carton, with two rows of bluntly pointed cusps, unlike the washboard-like surface of elephant or mammoth teeth. We now know that these teeth were adapted for browsing from trees, but early interpreters thought they were carnivorous teeth, and pictured the animal as something like a hippo. Comparative studies and more complete fossils gave it its proper elephantine form but also confirmed that nothing like it was known to be alive.

Photo taken by Justin Tweet, used with Permission of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

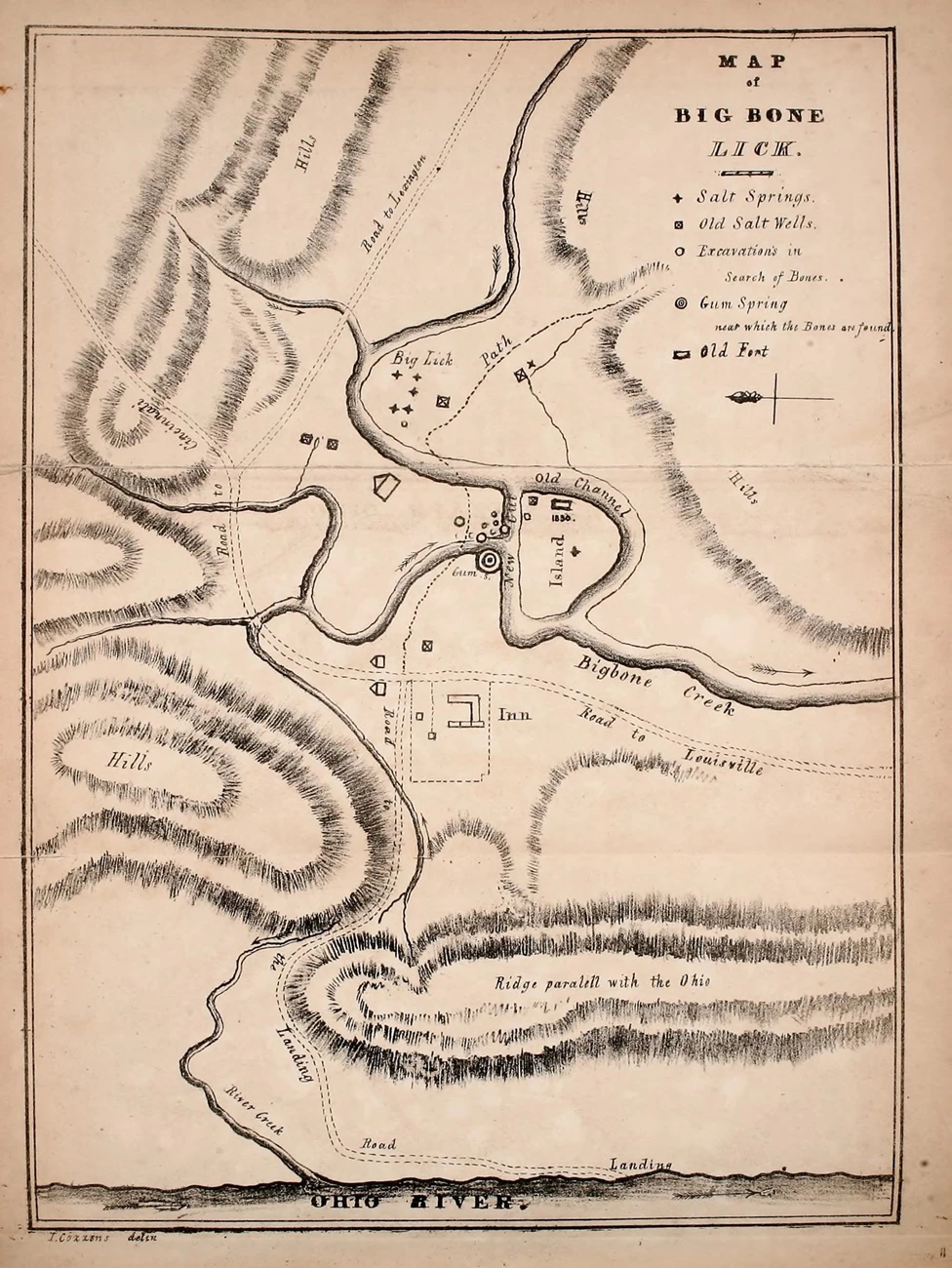

Because collecting at Big Bone Lick began so long before paleontology was a science, with the last significant surficial fossils removed only a few years after the Civil War, the actual science of the site is not as well-known as we might expect. For a long time, the most authoritative report had been published in the 1830s (Cooper 1831). It was not until the 1960s that modern scientific excavation occurred there, under the University of Nebraska (Schultz and others 1963, 1967). This project focused on describing the sedimentary layers and faunal zones. A more recent project by the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Museum Center focused on dating the deposits and studying their paleoecology (Tankersley and others 2015). Big Bone Lick, being near a major river, has layers representing intervals of river fill and erosion. Under different conditions rivers cut out valleys or fill them, creating a series of nested terraces where the oldest deposits are found both at the edges of the valley and below younger fills. In the Big Bone Lick area, there are three main deposits. The oldest was deposited in the Late Pleistocene, about 25,000 to 19,000 years ago. This deposit holds large numbers of fossils of mastodons, sloths, and other extinct animals. Bones are generally found disassociated, rather than in articulation. There are also younger deposits from about 14,000 to 12,000 years ago, at the very end of the Pleistocene, and 5,000 years ago to the present, from the Holocene. Because animals have continued to be attracted to the salt even after the extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene, the Holocene deposits also have many bones, but these are of modern mammals such as bison, deer, and elk. The bone beds are often thought to be the result of miring, but there are no fossils of large carnivores that would have been attracted to prey. However, the middle bed also has Paleoindian artifacts, providing evidence for hunting and butchering (Storrs and others 2023).

Map published by William Cooper (1831).

The Pleistocene animals of Big Bone Lick include many of the most famous Ice Age forms, among them ground sloths, mastodons and mammoths, extinct horses, extinct bison, musk oxen, and stag moose. Caribou also lived here, showing the colder climate. Interestingly, there is little evidence for large predatory mammals. Also, although the University of Nebraska team screenwashed for bones of small animals, no such fossils were found. Four accepted fossil species are known to have been named from Big Bone Lick specimens: the extinct bison Bison antiquus, the musk ox Bootherium bombifrons, the stag moose Cervalces scotti, and the ground sloth Paramylodon harlani. In addition, several early names now known to be synonyms of the American mastodon were named from fossils found here.

NPS photo by Vincent Santucci.

Today, bones are not as easily found at Big Bone Lick as they were in the 18th and 19th centuries, but the site can still be visited. Big Bone Lick is now in Kentucky’s Big Bone Lick State Historic Site, previously Big Bone Lick State Park. Visitors can see the salt springs that brought animals here, with sculptures of the ancient animals to set the scene. There is also a museum at the visitor center, showing examples of the various fossils. A herd of bison also roams part of the site. Big Bone Lick’s place in American paleontology and history has been recognized in many ways. Not only has the state of Kentucky recognized it, but it is also on the National Register of Historic Places (1972), a National Natural Landmark (2009), a location recognized on the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail (2019), and most recently (2024), it was named a National Historic Landmark, one of 17 places to be both a National Natural Landmark and a National Historic Landmark.

NPS photo by Vincent Santucci.

Administered by the National Park Service, the National Natural Landmarks Program recognizes and supports the voluntary conservation of exemplary biological and geological sites that illustrate the nation’s natural heritage, including those that contain significant paleontological resources. National natural landmarks are designated by the Secretary of the Interior and are owned by a variety of public and private stewards. To date, significant paleontological resources have contributed, in whole or in part, to the designation of 58 National Natural Landmark sites across the country, and paleontological resources are known at many others as well. These landmarks represent the range of geologic history from very early marine life 510 million years ago to more recent (40,000 years ago) fossil mammals.

Photo courtesy of Big Bone Lick State Historic Site.

References

Cooper, W. 1831. Notes of Big-bone Lick, Including the various explorations that have been made there, the animals to which the remains belong, and the quantity that has been found of each; with a particular account of the great collection of bones discovered in September, 1830. Monthly American Journal of Geology and Natural Science 1(4): 158–174, 1(5): 205–217.

Schultz, C. B., L. G. Tanner, F. C. Whitmore, Jr., L. L. Ray, and E. C. Crawford. 1963. Paleontologic investigations at Big Bone Lick State Park, Kentucky: a preliminary report. Science 142: 1167–1169.

Schultz, C. B., L. G. Tanner, F. C. Whitmore, Jr., L. L. Ray, and E. C. Crawford. 1967. Big Bone Lick, Kentucky: A pictorial story of the paleontological excavations at this famous fossil locality from 1962 to 1966. University of Nebraska News, Museum Notes 33: 1–12.

Storrs, G. W., H. G. McDonald, E. Scott, R. A. Genheimer, S. E. Hedeen, and C. E. Schwalbach. 2023. Field guide to Big Bone Lick, Kentucky: Birthplace of American vertebrate paleontology. Kentucky Geological Survey, series 13, Special Publication 2.

Tassy, P. 2002. L’émergence du concept d’espèce fossile le mastodonte américain (Proboscidea, Mammalia) entre clarté et confusion. Geodiversitas 24(2): 263–294.