Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 11, No. 1, Spring 2019.

Article

A Chance Discovery Reveals a Rich Fossil Shark Record From the Carboniferous of the Grand Canyon

Article by John-Paul M. Hodnett. Archaeology Program, Maryland-National Capital Parks and Planning Commission

February 26th, 2019 marked the centennial celebration of the establishment of the Grand Canyon as the 15th national park (GRCA) in the United States. Even before becoming a national park, the Grand Canyon has been inspiring visitors, whether they be explorers, artists or even tourists, by its spectacular views of its vast, nearly 2 billion years of geologic history.

As a vertebrate paleontologist, the Grand Canyon has left its own mark on me. I have had the opportunity to work with fossils from many sections of the canyon in museums across the country in my various research projects. These projects have ranged from Late Pleistocene large cat fossils from Rampart Cave to Paleozoic fish. The latter project has become a more focal point for myself, and last December my co-author David K. Elliott from the Department of Geosciences at Northern Arizona University and I published Carboniferous chondrichthyan assemblages from the Surprise Canyon and Watahomigi formations (latest Mississippian–Early Pennsylvanian) of the western Grand Canyon, Northern Arizona with open access in the Journal of Paleontology Memoirs. This publication presents the first extensive vertebrate body fossil assemblage from the Paleozoic of the Grand Canyon and it all started with someone cleaning out an office closet.

Image courtesy of George Billingsley

In the early spring of 2012 Dave Elliott was presented with a large shoebox by former NAU geologist Carrie Brugger-Schorr, who was in the process of cleaning out an office that was previously occupied by retired NAU professor Stanley Beus. The shoebox, which had been in the office closet, contained micropaleontology slides that held conodonts and micro-vertebrate fossils and each slide had been labeled with a unique letter and number code. However, there was no other locality information with the specimens. At the time, I was still living in Flagstaff and I was working with Dave on various Late Paleozoic fish fossils from Arizona. The micro-vertebrates consisted primarily of the isolated scales and teeth of fish, most of which were chondrichthyans. Though highly delicate, these fossils were in great shape and easily identifiable, but their provenance still remained a mystery. Stanley Beus was our first clue to solving the locality mystery of these fossils.

While going through publications on Paleozoic geology of the Grand Canyon, Dave and I came across a 1999 memoir published by the Museum of Northern Arizona on the geology and paleontology of the Surprise Canyon Formation edited by George Billingsley and Beus. Within this volume the locality markers matched most of the micropaleontology slides. Further research led to a 1992 NAU geology master’s thesis by Harriet Martin, a student of Beus’s, which was on the conodont biostratigraphy and paleoenvironment of the Surprise Canyon Formation. This thesis had the other locality markers missing from the 1999 memoir. The slides in the shoebox were part of this thesis work and memoir volume and were the material not presented. This was our “Eureka” moment!

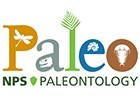

The Surprise Canyon Formation represents Latest Mississippian karst and paleo-valley deposition that cut into the Redwall Limestone approximately 320 million years ago during a short uplift and marine transgression event. At this time, what would become the Grand Canyon was positioned just south of the paleoequator. These paleo-valleys began as shallow fluvial and estuary systems that began to fill into a shallow marine embayment as the marine transgression continued. Fossils from the Surprise Canyon Formation come from three main units: the lower member represents the initial karst, fluvial, and estuary systems which contain large botanical remains (primarily tree logs); the middle member is the start of the marine embayment with invertebrate bioherms present; and the upper member is a deeper embayment phase. By the Early Pennsylvanian, these paleo-valleys were completely filled with the marine deposition we identify as the Watahomigi Formation today.

The Surprise Canyon Formation was first recognized in the western Grand Canyon in the 1960s, but wasn’t formally described until the work of George Billingsley and Stanley Beus in 1985. Billingsley’s and Beus’s field work (late 1970s to early 1980s) covered both GRCA on the north side of the Colorado River and the Hualapai Nation on the south side. Much of their field research was in remote sections of the western Grand Canyon, and at times field crews had to be air-dropped by helicopter. Macro- and micro-fossils were collected from multiple sites in both the Surprise Canyon Formation and Watahomigi Formation, most of which are in the Museum of Northern Arizona collections. The one exception was the macro vertebrate fossils which were sent to Richard Lund of Adelphi University for initial identification. He later sent them to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History for curation.

Dave and I were able to place the micro and macro vertebrate fossils within the stratigraphic context of the Surprise Canyon and Watahomigi Formations based on the detailed work by George Billingsley, Stan Beus, and Harriet Martin. We focused on the chondrichthyans as they made up the majority of the vertebrate materials in the form of teeth and dermal elements (denticles and spines). Many of the teeth we studied were a millimeter or less in size. We soon realized we had some interesting results.

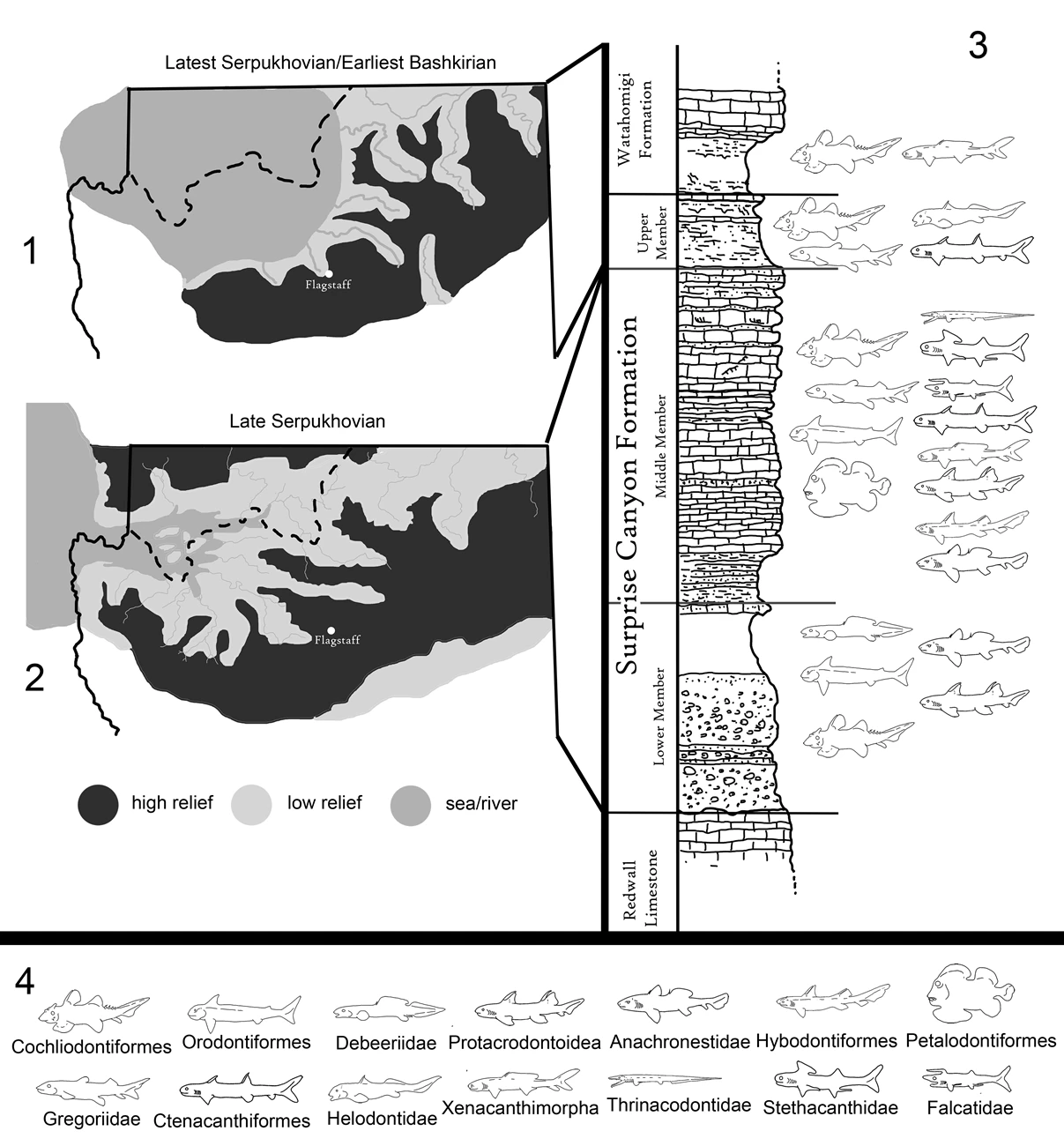

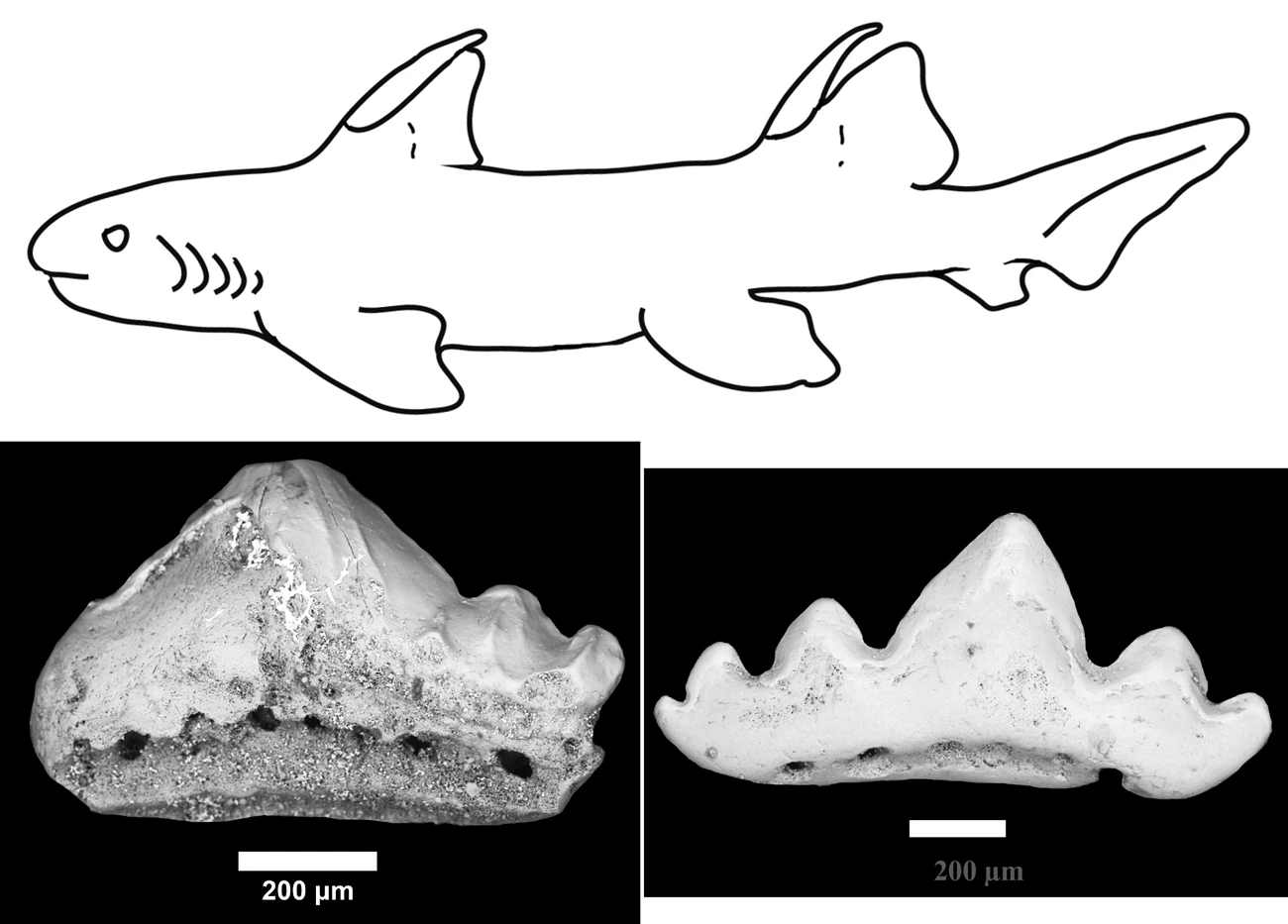

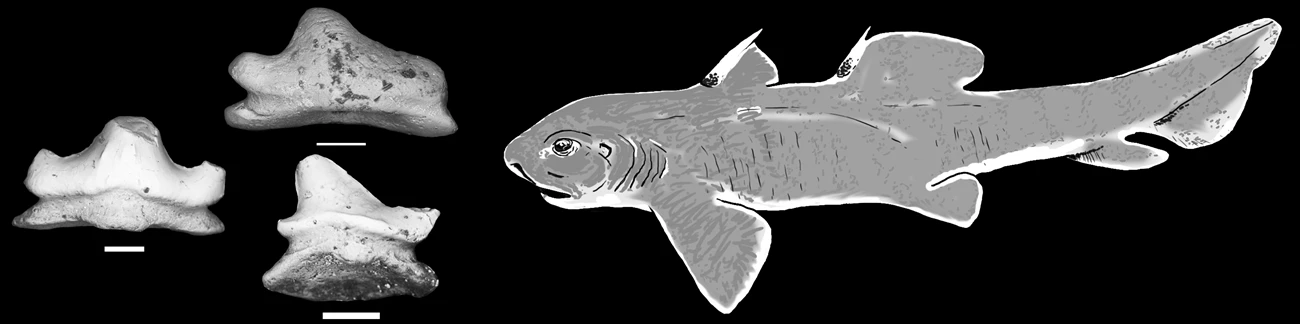

The Surprise Canyon Formation has a rich chondrichthyan assemblage with 31 taxa including the eel-like Thrinacodus gracia, early stem chondrichthyans known as the symmoriids which have unique shaped dorsal spines, hybodont sharks, neoselachians (members of the modern sharks and rays lineage), one of the oldest member of the whorl toothed eugenodonts (a group that includes Helicoprion), and early relatives of modern ratfish (Holocephalii). Of these 31 taxa from the Surprise Canyon Formation, four were new taxa. We have two new protacrodonts (ancestors to the hybodont and neoselachian branch of sharks) which we named Microklomax carrieae (Carrie’s little heap of stones; in honor of Carrie Bugger-Schorr) and Novaculodus billingsleyi (Billingsley’s razor-tooth; in honor of George Billingsley). Both protacrodonts are a temporal extension for this group of sharks and show divergent feeding niches with Microklomax having a durophagous dentition suited for crushing and Novaculodus with a more blade-like hyper-carnivorous dentition. Two new ancestors to the modern shark lineage included Cooleyella platera, which had simple single disk-like cusps, and Amaradontus santuccii (Santucci’s channel tooth; named in honor of NPS paleontologist Vincent Santucci), which has a more complex heterodont dentition. Both Cooleyella and Amaradontus would have been very small sharks (under a meter long) but have dental traits that can be traced to modern rays and sharks, including the estimated 18 meters (59 feet) long megalodon (Otodus megalodon).

We also found some biogeographical trends within the Surprise Canyon Formation samples. The assemblage of the lower fluvial/estuary member was primarily composed of early modern shark relatives and holocephalans, suggesting that these early sharks and holocephalans may have had a higher tolerance to lower salinity than their modern relatives. The middle marine member had the richest sample of chondrichthyans and included the only sections where Trinacodus and the symmorrids occurred. The symmorrids themselves also varied taxonomically from east to west, with one form found more commonly in the shallower eastern embayment and another taxon more common in the deeper western embayment. By the upper, deeper marine member we see less diversity, but the larger macro vertebrates are more prevalent. The Surprise Canyon Formation fauna also has many taxonomic similarities to the Bear Gulch Limestone fauna of equivocal age from Montana, which is world-renowned for its Lagerstätte (sedimentary deposit with exceptional fossil preservation) grade fossils.

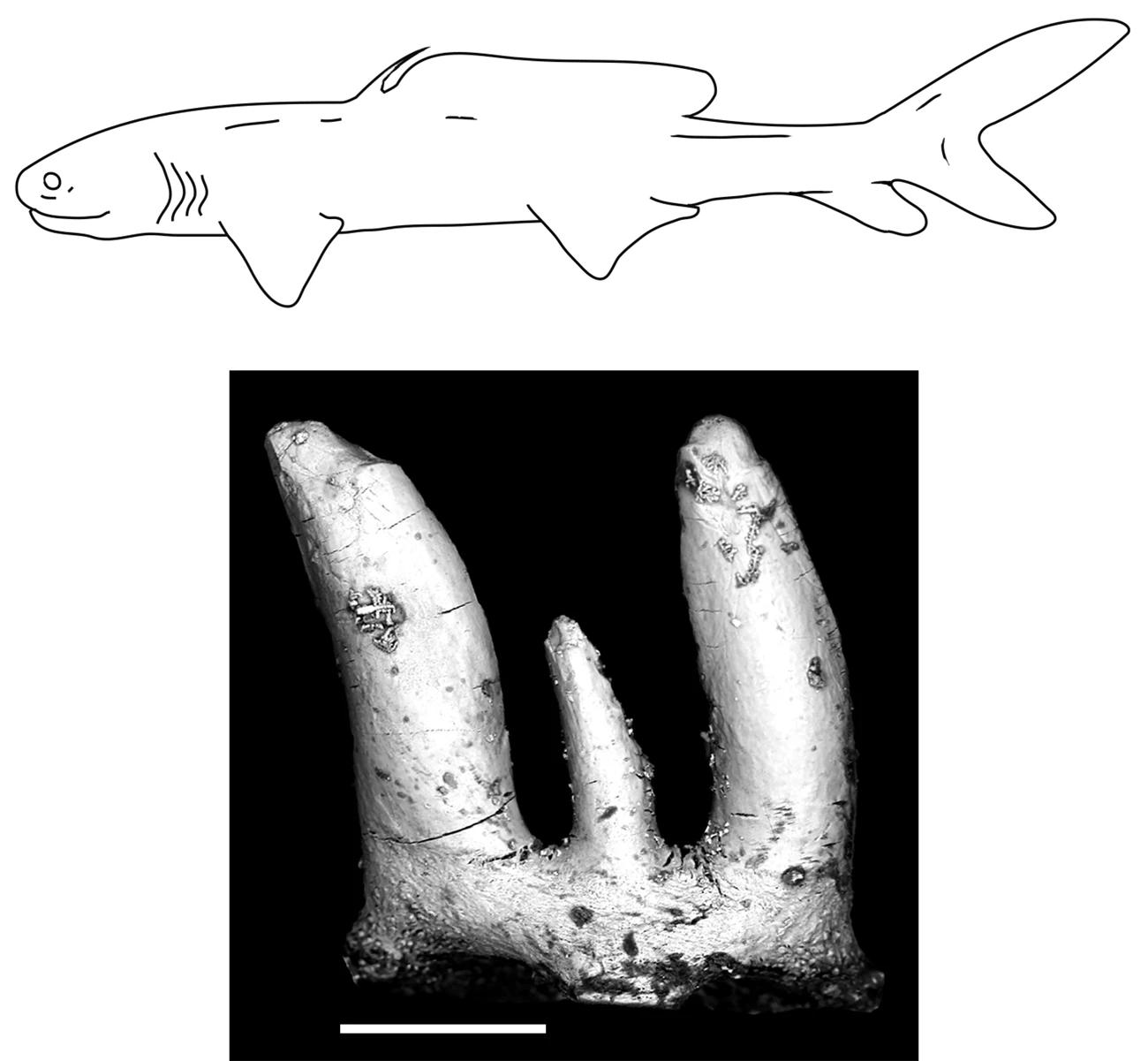

The Watahomigi Formation, at present, has only yielded two taxa of chondrichthyans. One is a new taxon of xenacanth shark we dubbed Hokomata parva (little Hokomata). Hokomata is a mischievous deity from the Grand Canyon creation story of the Hualupai and Havasupai tribes and is identified as the one who caused a great flood that would later carve the Grand Canyon. Xenacanths are a group of sharks known from primarily freshwater localities but Hokomata was collected from the marine deposits that make up the Watahomigi Formation. The second chondrichthyan described from this formation is Deltodus sp., a holocephalan, known only from a single tooth plate. With concentrated field work, we feel there is probably a greater record of chondrichthyans and other vertebrates within the Watahomigi Formation awaiting to be discovered.

The work with the Surprise Canyon Formation is not over. Aside from the chondrichthyans, there were also a number of small teeth and scales from bony fish (Actinopterygii) that were a part of the samples collected by Billingsley and Beus. Most excitingly, there are a couple of small jaw elements that may represent small amphibians. These could be the first Late Paleozoic tetrapod body fossils collected from the Grand Canyon! There are also other vertebrate records from the Temple Butte Limestone, Redwall Limestone, the Supai Group, and Kaibab Limestone. If explored, these rocks could reveal a richer Paleozoic vertebrate history at the Grand Canyon.

Suggested Reading

Billingsley, G.H., and Beus, S.S. 1999. Geology of the Surprise Canyon Formation of the Grand Canyon, Arizona. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin: 61, 254 pp.

Hodnett, J.-P. M., and Elliott, D.K. 2018. Carboniferous chondrichthyan assemblages from the Surprise Canyon and Watahomigi formations (latest Mississippian-Early Pennsylvanian) of the western Grand Canyon, Northern Arizona. Journal of Paleontology, V. 92, Memoir 77, p. 1-33

Martin, H., 1992, Conodont biostratigraphy and paleoenvironment of the Surprise Canyon Formation (Late Mississippian) Grand Canyon Arizona [MS thesis]: Flagstaff, Northern Arizona University, Arizona, 298 p.

Last updated: May 10, 2019