The War of 1812 served as an important turning point for establishing a sense of sovereignty and a shared history among Americans. But it also helped to develop distinct mythology for the young nation -- from Uncle Sam to the Star-Spangled Banner.

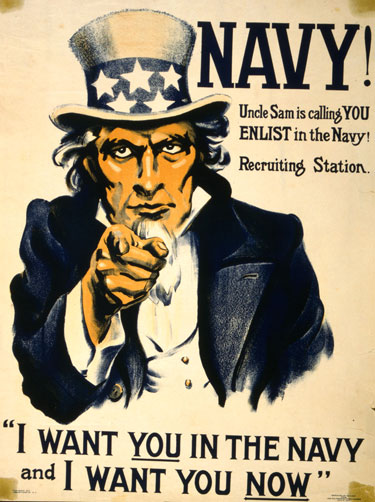

The Birth of Uncle Sam

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

A New York town found a way to promote itself, at least indirectly, through its connections with the War of 1812. No battle was fought at Troy, New York, but the city is now reckoned as the birthplace of “Uncle Sam.”The personification of the US federal government, Uncle Sam, dates from the War of 1812, though few connect the two. During the conflict, one Sam Wilson of Troy, New York, supplied provisions to American troops in the northern theater, often shipping this material in barrels marked with the initials “U.S.” Legend has it that a soldier asked what the “U.S. stands for” and received this reply: “Why, Uncle Sam Wilson. It is he who is feeding the army.” The attribution caught on, so much so that a Troy Post article on September 7, 1813, reported, “This cant name for our government has got almost as common as John Bull.” The rest, as they say, is history.

A Song for a Nation

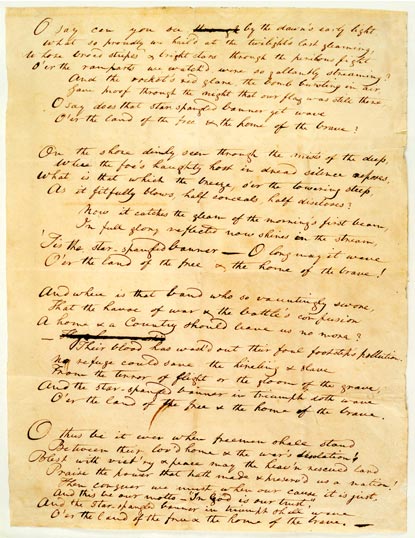

Maryland Historical Society

In the end, the most lasting contribution of the War of 1812 to American public memory has been Francis Scott Key’s “The Star-Spangled Banner,” which still proudly waves as the country’s national anthem. After Baltimore’s successful defense in 1814, Key composed a poem, “The Defence of Fort McHenry.” He later set its words to the tune of a popular English drinking song, “To Anacreon in Heaven,” and its name was changed to “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The heroic air employs numerous stanzas to proclaim national survival, symbolized by the flag waving over a besieged Baltimore fort. Who can fail to recall those immortal words from the third verse celebrating American destruction of its British foes? “Their blood has wash’d out their foul footsteps’ pollution. / No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight o the gloom of the grave.” Actually, nearly everyone has forgotten these embarrassingly blood-soaked phrases, from a time when slavery still existed in the United States (but not in Britain), along with the lyrics in every verse beyond the first. Even the anthem’s first verse has not fared well: “Oh, say can you see, by the danzerly light?” is a question many a schoolchild has asked, ingeniously crafting a new adjective for early morning.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” was not immediately embraced or always treated with reverence. Temperance advocates of the 1800s parodied it, for example: “Oh! Who has not seen by the dawn’s early light, / Some bloated drunkard to home weakly reeling?” Foreign-language versions have been common. German and Latvian translations date to the 1860s, for example, and later, Yiddish, French, and other renditions have appeared, including a Spanish-language anthem that caused controversy amid the immigration debates of 2007. In fact, the US Bureau of Education had printed the anthem in Spanish in 1919 to cultivate among immigrants a love of their new country. Not until 1931, following some 40 attempts over 20 years, did Congress finally make “The Star-Spangled Banner” officially the US national anthem. Americans have largely forgotten the War of 1812, but its “Star-Spangled Banner” lives on as more than a relic, oddly embodying America as a place of adaptation, creativity, and transformation.

Part of a series of articles titled Legacies: The War of 1812 in American Memory .

Previous: Letting bygones become bygones

Last updated: April 2, 2015