"This thing of Saint-Gaudens strikes me as real perfection." Henry James, American writer

Article

The Robert Gould Shaw Memorial

Matt Teuten

Standing on the Boston Common facing the Massachusetts State House, The Robert Gould Shaw 54th Massachusetts Memorial remains one of the country's most inspirational memorials. Commemorating one of the country's first all-Black regiments during the Civil War, the Memorial stands for the effort and sacrifice of the solders of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, as well as their fight for justice and equity that remains ongoing today. Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens spent 14 years of his life developing the work—longer than any other of his career—to create this stirring and celebrated masterpiece. The Memorial took years of dedication not only from its creator, but also of community members and supporters of the famous regiment to advocate for its creation. Over thirty years after the 54th Regiment's fateful assault on Fort Wagner, local and national leaders dedicated the Memorial on May 31, 1897.

Massachusetts Historical Society

Advocating for the Memorial

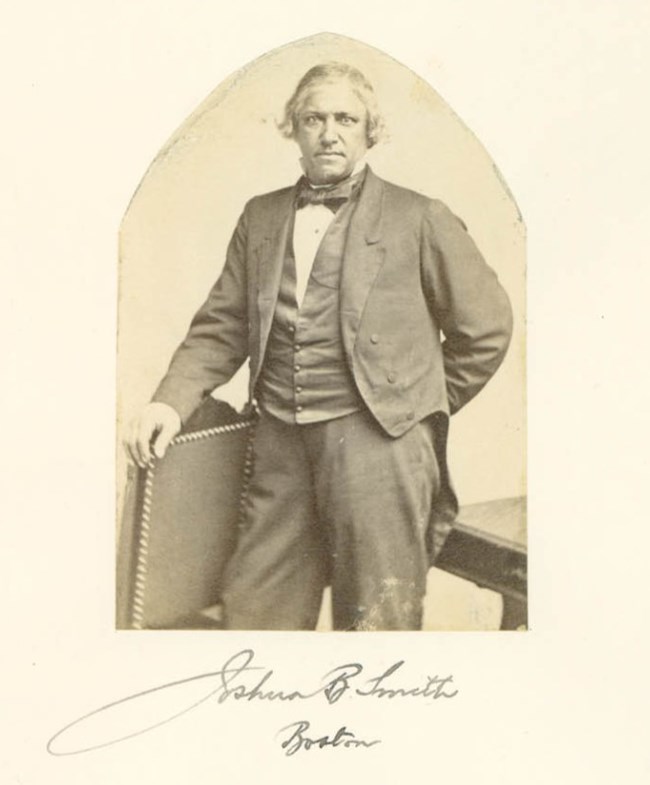

Calls for a memorial to commemorate Colonel Robert Gould Shaw began in 1863 soon after the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, South Carolina. Historians largely regard Black Bostonian Joshua Bowen Smith as the originator of this idea. Smith had close ties to the Shaw family; he once worked for them as a servant before starting his own catering business. He encouraged his close friend, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, to support the endeavor.[1] The efforts of soldiers and community members in South Carolina aided Smith's work. Funds began pouring in to establish a monument to Col. Shaw in South Carolina, near the site where the colonel fell and was later interred in a mass grave along with soldiers from his regiment.

However, some opposed the monument in South Carolina for a variety of reasons. Member of the 54th, Corporal James Gooding objected to the location of the monument on "soil which the enemies consider their own." Gooding wrote to the Boston Advertiser: "We are ready to put in our mite, but we would rather see it raised on old Massachusetts soil. The first to say a black was a man, let her have the first monument raised by black men's money, upon her good old rocks."[2] Some also did not want the memorial to focus solely on the fallen leader. Abolitionist Lydia Maria Child wrote to the National Anti-Slavery Standard, "I was glad Gen. Saxton proposed to the freedmen to erect a monument to Col. Shaw, but the colored soldiers who fell ought to have a monument also."[3] Even Francis Shaw, Col. Shaw's father, voiced support for a more-encompassing monument, suggesting that "the monument, though originated for my son, ought to bear, with his, the names of his brave officers and men, who fell and were buried with him."[4] Due to these reasons as well as local hostility and unstable ground, the first efforts to establish a memorial did not succeed.

Boston Public Library

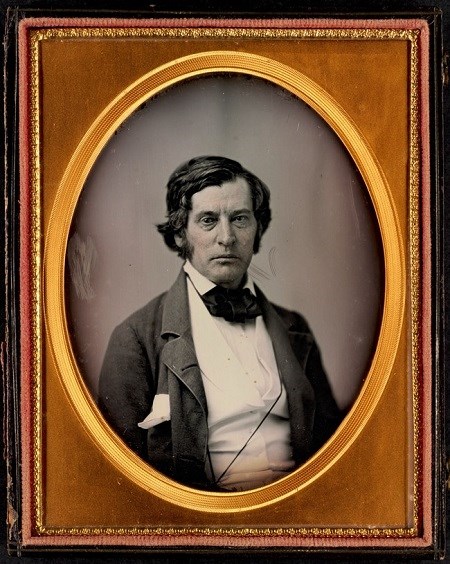

In 1865, when the War ended, new calls for a memorial arose in Boston. Charles Sumner now gave rousing support for the endeavor:

The monument should be in Massachusetts, where the martyr was born, and where the regiment was born also... Of course, no common stone or shaft will be sufcient [sic]. It must be of bronze. It must be an equestrian statue. And there is a place for it. Let it stand on one of the stone terraces of the steps that ascend from Beacon street to the State House. It was in the State House that the regiment was equipped and inspired. It was out of the State House that the devoted commander rode to death. Let future generations, as long as bronze shall endure, look up [at] him there riding always, and be taught by his example to succor the oppressed and to surrender life to duty...[5]

In response to this call, Massachusetts Governor John Andrew called a meeting for all those interested in the creation of a monument. This resulted in the formation of a committee of 21 prominent Bostonians, including Charles Sumner, Joshua Smith, and notable Beacon Hill community leader Rev. Leonard Grimes.[6]

After the committee determined the monument would be an equestrian statue of Col. Shaw, fundraising began in earnest. Rich and poor, Black and White, from Boston and beyond—those of all backgrounds donated to the cause. Shaw Memorial fund treasurer Edward Atkinson recalled, "I believe that no one was ever asked to subscribe; all the contributions have been of a purely voluntary character, most gladly given."[7]

Despite this earnest reaction to the cause, the creation of the Memorial stalled for over a decade. Active supporters such as Sumner, Andrews, and Smith passed away during this standstill. Finally, in August 1882, the committee commissioned sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to create an equestrian statue to commemorate Col. Shaw.

Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, National Park Service

Making the Memorial

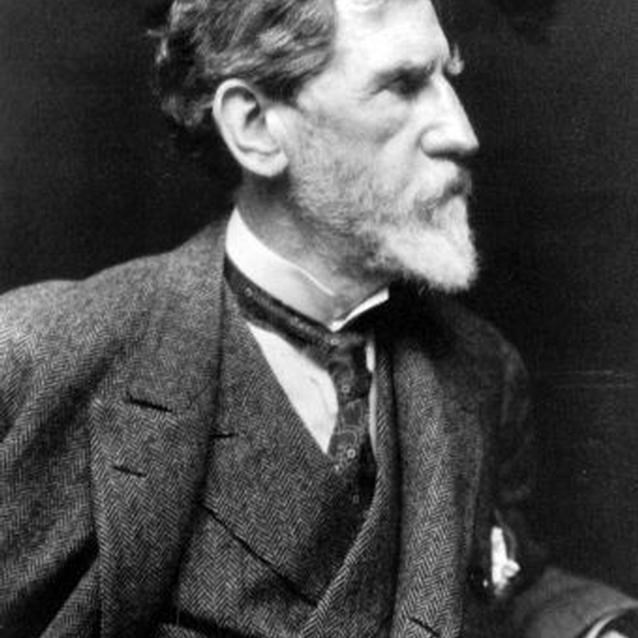

An Irish-born sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens immigrated to the United States at a young age. He returned to Europe to study sculpting at the École des Beaux-Arts in France. Saint-Gaudens won his first major public commission in 1876 with a monument to Admiral David Glasgow Farragut in New York. This well-received work boosted his status as an artist, and Saint-Gaudens became a sought-after sculptor.

When Saint-Gaudens won the commission for the Shaw Memorial, there appeared to be a general consensus that the memorial would be an equestrian statue. Early drawings and sketches reflect this concept. However, it soon became clear that an equestrian statue did not please interested parties. Saint-Gaudens reflected:

the Shaw family objected on the ground that, although Shaw was of a noble type, as noble as any, still he had not been a great commander, and only men of the highest rank should be so honored. In fact, it seemed pretentious. Accordingly, in casting about for some manner of reconciling my desire with their ideas, I fell upon a plan of associating him directly with his troops in a bas-relief, and thereby reducing his importance.[8]

The concept of Shaw on horseback with marching soldiers might have been inspired, at least in part, by the painting "Campagne de France 1814" (1864) by Jean-Louis Ernest Meissonier, which depicts Napoleon on horseback with rows of infantry in the background.[9] In depicting the soldiers, Saint-Gaudens strove for realism. In this relief, he wanted to show a range in facial features and age, as likely found among the soldiers of the regiment. In the few previous inclusions of African Americans in public monuments, artists often fell into common stereotypes and tropes. Saint-Gaudens instead focused on depicting the Black soldiers with realistic features and accurate accompanying clothing and accoutrements. Although striving for this realism, it appeared Saint-Gaudens did not rely on any existing photographs of members of the 54th, nor did he apparently meet with any members while he was creating the studies of the soldiers. Instead, Saint-Gaudens hired Black men he came across on the street near his studio. In all, Saint-Gaudens created some 40 models of heads to use as studies.[10]

From about 1883 to 1897, Saint-Gaudens methodically worked on the bas relief. To him, working on the monument "became a labor of love."[11] During this time, Saint-Gaudens fulfilled other smaller commissions, much to the chagrin of the Memorial committee. Saint-Gaudens defended his stance, considering the longevity of a public monument like the Shaw:

My own delay I excuse on the ground that a sculptor's work endures for so long that it is next to a crime for him to neglect to do everything that lies in his power to execute a result that will not be a disgrace. There is something extraordinarily irritating, when it is not ludicrous, in a bad statue. It is plastered up before the world to stick and stick for centuries, while man and nations pass away. A poor picture goes into the garret, books are forgotten, but the bronze remains to accuse or shame the populace and perpetuate one of our various idiocies.[12]

The final hurdle that remained in the final years of the making of the memorial surrounded the inscriptions to be included. Specifically, whether or not to include all members of the regiment, or just the five white captains who fell. Josephine Lowell, Col. Shaw's sister, advocated for the inclusion of all soldiers of the regiment: "I want very much to have the names of all men of the 54th killed at Fort Wagner & afterwards, put on the base" as she believed omitting them confirmed the belief "that it is only men with rich relations and friends who can have monuments."[13] Lowell's efforts were fruitless. Although the final inscriptions remark on the historic nature of the regiment, the original names included only the white officers. This later became rectified in the early 1980s.

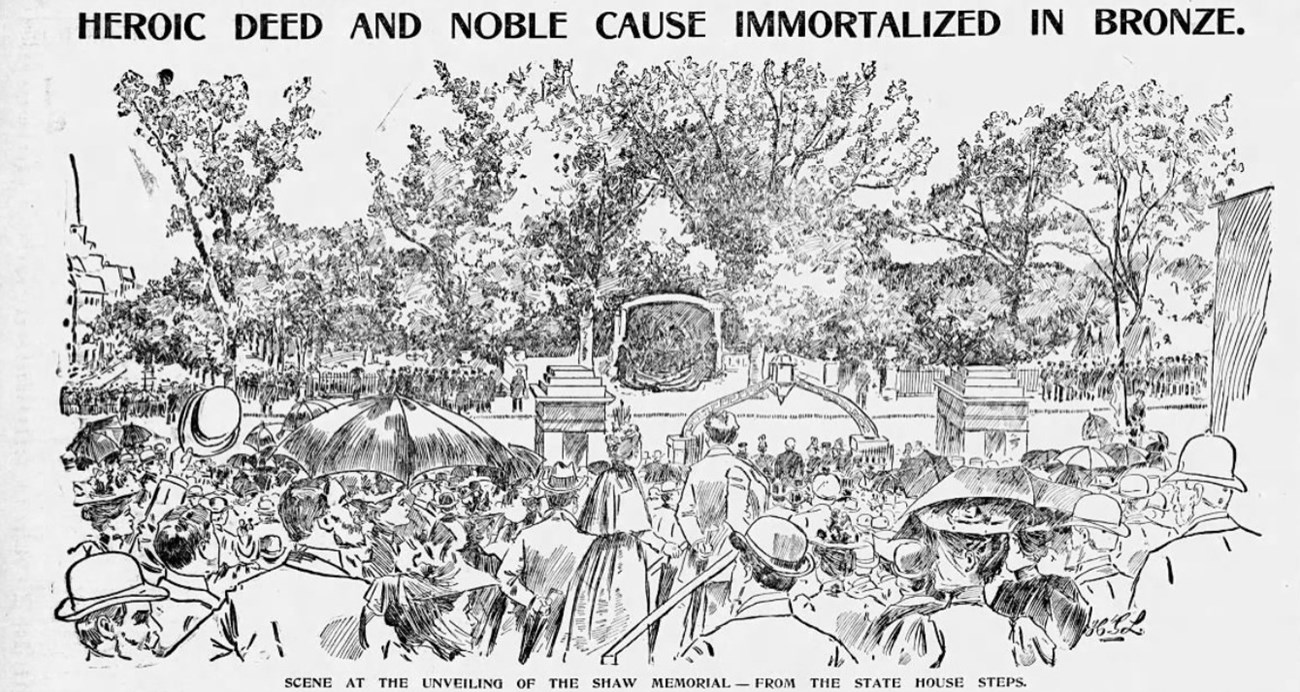

Boston Globe, June 1, 1897.

Unveiling the Memorial

Finished in early May 1897, the 11 x 14 ft. bronze cast of the Shaw Memorial was installed on Boston Common on May 21 under the supervision of Saint-Gaudens. Two large US flags covered the sculpture until the unveiling on May 31. On the day of the unveiling, the weather was overcast with a light, misty rain. In spite of this, a festive feeling hung in the air as spectators lined the streets. A military procession began at 10am, led by 65 veterans of the 54th Massachusetts. Some of the officers wore their Civil War uniforms but most of the enlisted soldiers wore their frock coats. Among them, Sergeant William Carney carried the US flag. Black veterans from the 55th Massachusetts Infantry and the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry joined this procession. As the military units marched past the memorial, the 54th veterans laid a large wreath of lilies of the valley before the monument. Dignitaries and speakers followed in carriages.[14]

At 11:17 a.m. two young nephews of Robert Gould Shaw unveiled the memorial. The crowd cheered, a band struck up "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," and an artillery battery on the Boston Common fired a 17-gun salute. Simultaneously, three warships in Boston harbor each fired a 21-gun salute.[15]

Watching the events of the unveiling and the procession of the 54th veterans deeply moved Saint-Gaudens, who recalled:

Many of them were bent and crippled, many with white heads, some with bouquets... The impression of those old soldiers, passing the very spot where they left for the war so many years before, thrills me even as I write these words. They faced and saluted the relief, with the music playing 'John Brown's Body'.... They seemed as if returning from the war, the troops of bronze marching in the opposite direction, the direction in which they had left for the front, and the young men there represented now showing these veterans the vigor and hope of youth. It was a consecration.[16]

While honoring the past efforts of the historic regiment and its fallen leader, some speakers remarked on the regiment's lasting legacy. Booker T. Washington noted that "this monument [stands] for effort, not victory complete. What these heroic souls of the 54th Regiment began, we must complete."[17]

Reception

Following the dedication of the Memorial, accolades came from around the country and beyond. Author Henry James, whose brothers fought in the 54th, wrote, "How I rejoice that something really fine is to stand there forever for R.G.S. and all the rest of them. This thing of Saint-Gaudens strikes me as real perfection."[18]

Many members of the 54th revered it as a fitting tribute to their fallen leader and comrades. 54th member Burrill Smith Jr. wrote to the Boston Herald that it should be protected:

As I was one of the 54th Massachusetts volunteer infantry who marched through the streets of Boston in the ranks of the old 54th regiment, I think that it is fitting that a fence be placed in front of the monument of Col. Robert G. Shaw. It is with feelings of pride every time I pass the spot where I, but a boy of 17 years, marched behind Col. Robert G. Shaw.[19]

Boston Public Library

Legacy

Over the past century, The Robert Gould Shaw 54th Massachusetts Memorial has been the source of inspiration for many. Thousands of reproductions and photographs dispersed across the country both immediately following the dedication and over the years since. The story of the famed regiment and its fearless commander has made its way into popular culture. Communities have renamed or created schools and institutions after Col. Shaw or soldiers; writers have penned poetry or songs referencing the regiment; and artists have produced their own renditions of the memorial or the heroic Battle of Fort Wagner. It is also believed the writer of the 1989 movie Glory became interested in the story of the 54th regiment after seeing the Memorial.[20]

Throughout the 1900s, the Memorial served as a place of commemoration and protest. It provided a sacred space for veterans of the famed regiment to remember their fallen comrades. It became a site of demonstration as activists fought for civil rights, equal access to public education, and international peace. Today, it continues to uphold the regiment's ongoing legacy of fighting for social justice.

Footnotes:

[1] Kathryn Grover, To Heal the Wounded Nation's Life: African Americans and the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial (Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park, 2021) 4.

[2] As quoted in Grover, To Heal the Wounded Nation's Life, 166.

[3] Grover, 167-168.

[4] Grover, 167.

[5] Grover, 171.

[6] Grover, 173.

[7] Grover, 176-177.

[8] Grover, 214.

[9] Grover, 216.

[10] Grover, 218. It is unclear whether or how Saint-Gaudens compensated the Black men he used as models for the soldiers. It must also be noted that in correspondence, the artist used demeaning and racist language when recounting his work with these models. Please see Grover's work for a more comprehensive discussion on his language and possible views.

[11] Grover, 224.

[12] Quote retrieved from Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park's webpage The Shaw Memorial.

[13] Grover, 229.

[14] Grover, 255-259.

[15] Grover, 261.

[16] Grover, 261-262.

[17] Grover, 274.

[18] Letter from Henry James to Miss Frances R. Morse, June 7, 1897, in Henry James, The Complete Works of Henry James (2017).

[19] Grover, 308.

[20] Roger Ebert, "Glory," RogerEbert.com, accessed May 2022, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/glory-1989.

Tags

- boston national historical park

- boston african american national historic site

- saint-gaudens national historical park

- civil war

- commermoration

- emancipation

- ethnic/cultural heritage

- military

- reconcilliation

- civil rights

- shaw memorial

- memorial

- 54th massachusetts regiment

- united states colored troops

- 54th gallery