Part of a series of articles titled The Waterford, Virginia National Historic District.

Article

Waterford, Virginia: From Mill Town to National Historic Landmark (Teaching with Historic Places)

(Bronwen Souders)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

Today, visitors to Waterford, Virginia, experience many of the same views as residents in the 19th century. A National Historic Landmark District, Waterford preserves the ambiance and many of the structures that characterized it during its heyday as a flour milling town in the 19th century. In fact, the village has changed so little in shape and size that founder Amos Janney would find it quite recognizable. He could stroll from his 1733 home to the area of his original mill and then on to the Quaker meeting house he founded in 1741.

In 1943, descendants of village families and newcomers interested in preserving the buildings, traditions, and rural character of Waterford formed the non-profit Waterford Foundation. The Foundation has played an important role in revitalizing the physical fabric of Waterford as well as increasing the public's knowledge of life and work in an early American rural community.

About This Lesson

This lesson plan is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Waterford Historic District" (with photographs), and materials in the collection of the Waterford Foundation, Inc.

Bronwen Souders, a member of the Waterford Foundation's education committee, wrote Waterford, Virginia: From Mill Town to National Historic Landmark. Jean West, education consultant, and the Teaching with Historic Places staff edited the lesson. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson focuses on changing life in a Quaker agricultural community and mill town. It can be used in American history, social studies, and geography courses in a unit on early industrialization or to illustrate how communities adapt to economic change.

Time period: 18th century to 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Waterford, Virginia: From Mill Town to National Historic Landmark

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 2A- The student understands how the factory system and the transportation and market revolutions shaped regional patterns of economic development.

Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

-

Standard 1A- The student understands the connections among industrializaton, the advent of the modern corporation, and material well-being.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Waterford, Virginia: From Mill Town to National Historic Landmark relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard C - The student explains and gives examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

StandardA - The student demonstrates an understanding that different scholars may describe the same event or situation in different ways but must provide reasons or evidence for their views.

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

-

Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land use, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

-

Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced, physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

-

Standard A - The student gives and explains examples of ways that economic systems structure choices about how goods and services are to be produced and distributed.

-

Standard B - The student describes the role that supply and demand, prices, incentives, and profits play in determining what is produced and distributed in a competitive market system.

-

Standard E -The student describes the role of specialization and exchange in the economic process.

-

Standard G - The student differentiates among various forms of exchange and money.

Theme VIII: Science, Technology, and Society

-

Standard B - The student shows through specific examples how science and technology have changed people's perceptions of the social and natural world, such as in their relationships to the land, animal life, family life, and economic needs, wants and security.

Theme X: Civic Ideals, and Practices

-

Standard C - The student locates, accesses, analyzes, organizes, and applies information about selected public issues - recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

Objectives for students

1) To identify stages in the economic development of Waterford.

2) To examine the role regional and national transportation networks played in linking this rural Virginia community with a wider world.

3) To determine why the appearance of Waterford has changed little over time, unlike many other communities.

4) To discover the history of their own community, including why it was founded and what changes in typical occupations have occurred.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) two maps of Waterford and the surrounding region;

2) three readings about Waterford, wheat production, and the mill's work;

3) two drawings of Waterford;

4) four photos of Waterford.

Visiting the site

Waterford is approximately 35 miles northwest of Washington, DC via Route 7 or the Dulles Toll Road and Greenway; follow Route 7 northwest to Route 9, then north on Route 662. The village is accessible year-round to visitors. Although the 90 or so dwellings are still in private ownership, the Waterford Foundation owns and interprets the mill and a number of other public buildings. For information, contact the Waterford Foundation, P.O. Box 142, Waterford, VA 20197, or visit the Foundation's web site.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

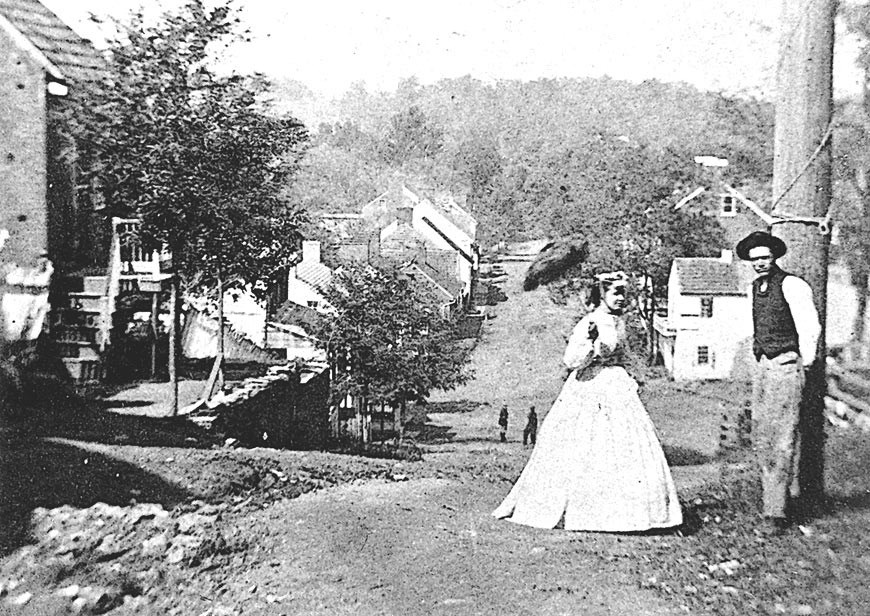

When might this photo have been taken?

Setting the Stage

A mill is a building equipped with machinery that processes a raw material such as grain, wood, or fiber into a product such as flour, lumber, or fabric. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Virginia's mills were powered by water in creeks or rivers. In a flour mill, water flowing over the mill wheel was converted by gears into the power to turn one of two burr stones. Kernels of wheat were then ground between the two stones. The grinding removed bran (the outer husk) from the wheat kernel, and then crushed the inner kernel into flour. Flour mills were an important part of rural communities across the country, including Waterford in the fertile Loudoun Valley of Virginia.

Among the earliest arrivals to this area were Amos and Mary Janney, members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). In 1733, Janney purchased 400 acres along Catoctin Creek. By the early 1740s, he had built a mill of logs for grinding flour and sawing wood. As fellow Quakers came to the area seeking fertile farmlands, a settlement grew up around "Janney's Mill." Local farmers brought their wheat to the mill for grinding, and by 1762, Mahlon Janney, Amos's son, had built a larger, two-story mill of wood on a stone foundation.

Through the end of the 18th century, the settlement at Janney's Mill drew Pennsylvania Quaker, German Lutheran, and Scotch-Irish Presbyterian small farmers. As Loudoun County built and improved roads, the village grew rapidly. Homes and shops were built, and in the 1790s the settlement was renamed Waterford. Waterford continued to prosper and reached its manufacturing height in the mid 19th century.

Locating the Site

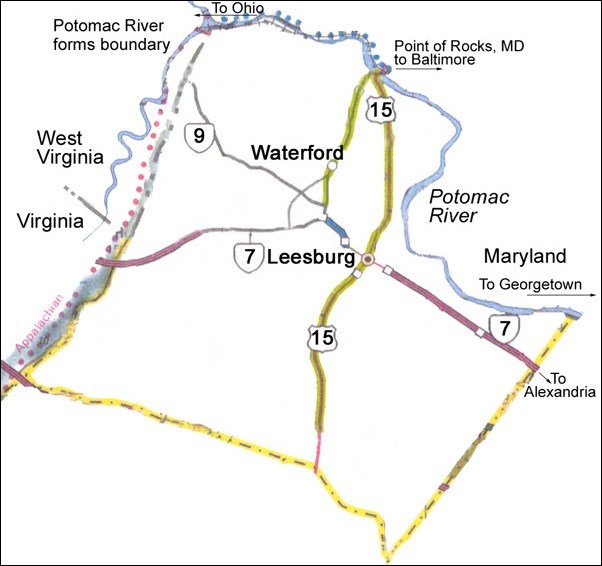

Map 1: Loudoun County, Virginia, in the 1870s.

Since its settlement in the mid-1700s, Loudoun County has been acclaimed for its fertile soil. In the 1850s and 1860s, Virginia was the fourth largest wheat producing state, and Loudoun was one of the state's top-producing counties. Thirty water-powered mills were processing a half-million bushels of Loudoun wheat by 1850.

In the 1700s, oxen took the flour to market in Alexandria. By 1826, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad were in operation through nearby Point of Rocks, Maryland. Waterford flour could be hauled there by oxen, then barged to Georgetown or taken by railcar to Baltimore. After the Civil War ended in 1865, and Loudoun's damaged Washington and Old Dominion railroad could be repaired and extended west beyond Leesburg, it was even easier for Waterford area farmers to get their flour to market.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate Waterford on Map 1.

2. Note the close distance between Waterford, Virginia and Point of Rocks, Maryland.

3. Describe how Waterford flour was transported to markets prior to the Civil War. Trace the possible routes on Map 1.

4. When the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad began to operate in Loudoun County, how do you think it affected the volume of traffic between Waterford and Point of Rocks?

Locating the Site

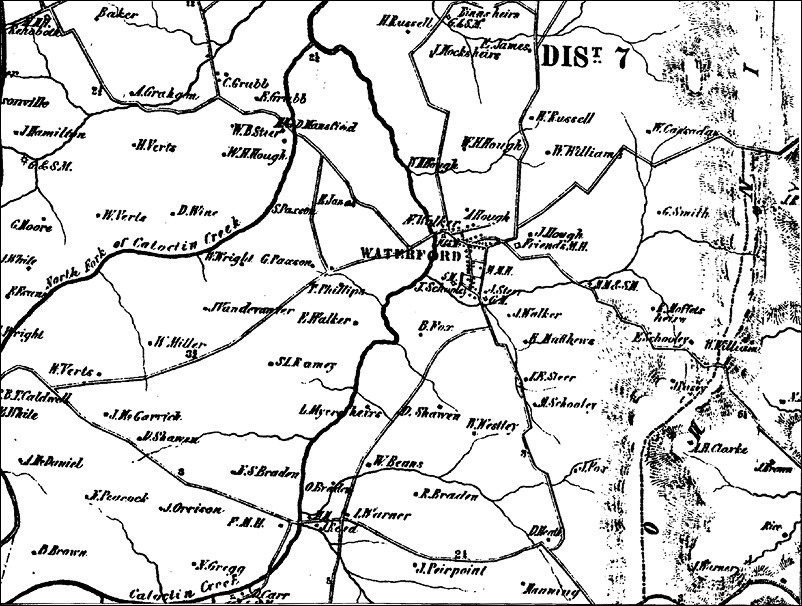

Map 2: Waterford and surrounding farms, 1853.

This map was adapted from the 1853 Yardley Taylor map of Loudoun County. All properties are shown as little squares, but the only properties named are those whose owners paid a subscription fee.

Questions for Map 2

1. Why would mapmaker Yardley Taylor ask for a subscription fee for farmers who wished to be included on his map?

2. Why might a farmer want his farm included on the map? Why might a farmer not want his farm listed on the map?

3. Notice the number of roads into, and out of, the village. Why would this be important to farmers as well as the miller?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Waterford: From Mill Town to National Historic Landmark

By 1835, a Virginia gazetteer noted that Waterford was a flourishing little village of "seventy dwelling houses, 2 houses of public worship, 1 free for all denominations, the other a Friends' meeting house, 6 mercantile stores, 2 free schools, 4 taverns, 1 manufacturing flour mill and 1 saw grist and plaster mill, and (in the vicinity) 2 small cotton manufactories. The mechanics are 1 tanner, 2 house joiners, 2 cabinet makers, 1 chair maker and painter, 1 boot and shoe manufacturer, 2 hatters, 1 tailor, &c. Population about 400 persons; of whom 3 are regular physicians."¹ The following year, in 1836, the thriving town was incorporated at its own request, and the 12 newly-elected commissioners appointed their first mayor, recorder, and sheriff.

By the middle of the 19th century wheat remained important to the local economy. Janney's second mill had been rebuilt and enlarged on the same foundation around 1818. The new three-and-a-half story brick mill doubled the previous capacity, reflecting the fertility and high wheat yield of the surrounding farmland. Quaker historian Asa Moore Janney noted that Yardley Taylor's 1853 map of Loudoun County showed 77 mills of various kinds in the county, of which 30 were wheat mills.

By the 1850s, Waterford's mill was producing flour for a wider market than just the village because the nearby Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and Baltimore and Ohio Railroad greatly improved the town's links to distant markets. Mill entries from 1849 show barrels of flour being hauled to Point of Rocks, Maryland, where they were loaded either onto Chesapeake and Ohio Canal barges or Baltimore and Ohio Railroad freight cars. In the Waterford area alone, by 1860, an estimated 80 farmers were producing more than 40,000 bushels of wheat, or about 500 bushels per farmer, an increase over the previous decade.²

The Civil War brought devastation to Waterford. Grain and crops were taken or destroyed by troops on both sides of the conflict. Lapsed Quaker Sam Means had to close his mill after Confederate forces seized his horses, wagons, and grain in 1862. He retaliated by forming the Independent Loudoun Rangers, the only army unit organized in Virginia to fight for the Union. It did not spare Waterford from damage by Union troops. Later in the war, during General Sheridan's "Burning Raid" of 1864, Union soldiers burned area barns to deny food for the Confederates and their horses. Relieved of his command in 1864 for refusing to obey orders, Means lived near Point of Rocks, Maryland until the war was over. Means never recovered financially from his previous losses. He sold the mill in 1868, moved to Washington, did not prosper, and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Back in Waterford, however, others were looking ahead to better times. Quakers from Waterford and nearby Lincoln founded the Catoctin Farmer's Club in 1868; members formed subcommittees to explore ways to broaden markets for local farmers. When the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad was extended west from the nearby county seat of Leesburg, past Waterford in 1870, it opened access to new markets.

Apparently the new mill owner, Charles Paxson, and his miller, J. F. Dodd, benefited from improved transportation connections. In 1885, they enlarged the brick mill significantly and installed the latest "roller mill" technology. The burr stones which used to grind the wheat kernels were replaced with porcelain rollers that successively crushed or rolled the wheat finer and finer, eliminating grit and producing a fine, white flour. The support industries for agriculture—harness makers, wagon builders, and blacksmiths—remained working in the village until the early 1900s.

Although Waterford grain had better access to markets, the village never returned to its pre-war level of manufacturing success because Waterford's villagers and area farmers were able to import cheaper machine-made goods—shoes, furniture, clothing, and farm equipment—from large manufacturing centers. They no longer supported local chairmakers, cobblers, and weavers, so these crafts began to disappear. As the artisans left, demand for new construction dwindled.

At the time of the Great Depression in the 1930s, the Waterford mill stopped grinding. In spite of continued high production of wheat in Loudoun County, local mills could no longer compete with huge mills located outside the area. The mill's machinery was sold as scrap iron for the war effort during the early part of World War II.

In 1943, village residents formed the non-profit Waterford Foundation to preserve Waterford's crumbling buildings, traditions, and rural character and to educate the public about life in early America. They used the mill to showcase 19th-century crafts. In October 1944, they began holding a three-day Homes Tour and Crafts Exhibit to highlight the town's arts, crafts, early history, and special architecture. Now the single largest event in Loudoun County, "the Fair" is the oldest juried crafts fair in Virginia and is nationally recognized for its educational outreach in an historic setting. The village is now home to residents who range from carpenters to commuters. The Waterford Foundation continues to educate thousands of student and adults each year and faces the challenge of rapid population growth that threatens to consume the farmlands of Loudoun County.

Questions for Reading 1

1. In the 1830s, what types of services were available to residents of Waterford?

2. Why was Waterford's economy damaged so badly during the Civil War? What helped the village recover?

3. What advances in transportation and mill technology caused larger mills to be built in Waterford?

4. When the mill finally stopped grinding flour, what happened to the economy and people of the town?

5. How did the economic conditions following the closing of the mills help preserve what is now Waterford's historic district?

Reading 1 was compiled from Joseph C. G. Kennedy, Agriculture of the United States in 1860, Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1864); U.S. Bureau of the Census, Loudoun County, Virginia, Statistics of Agriculture, 1850-1870 (Microfilm edition T1132, Roll 7); Sheri Spellman and Bronwen C. Souders, Walk With Us (Waterford Foundation, 1992); Bronwen C. Souders and Kathleen Hughes, Waterford's Agricultural History: 1733-1993 (Waterford Foundation: Special Education Exhibit, 1993); and Thomas Phillips and Nathan Walker, Waterford Mill Ledger (Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia).

¹ Joseph Martin, Gazetteer of Virginia and the District of Columbia (Charlottesville, Va.: 1835), 216.

² U.S. Bureau of the Census, Loudoun County, Virginia, U.S. Census Agricultural Statistics 1850-1870, Microfilm edition T1132, Roll 7, 347-408.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Early 19th-Century Wheat Farming Near Waterford

John Jay Janney, a distant cousin of Waterford founder Amos Janney, was born in 1812 near the Quaker settlement of Goose Creek, about 10 miles south of Waterford. Ninety-five years later, in Ohio in 1907, Janney penned his memories of his childhood. In addition to writing about all facets of life in Loudoun County in the 1820s, he outlined the farmer's duties regarding his crops for an entire year. The portions concerning wheat are excerpted here and describe farming activities similar to those around Waterford.

After [corn] harvesting was over [in the autumn], we plowed for next year's wheat crop, and when the ground was ready for sowing we hauled all the manure from the barn yard and the hog pen, usually a good supply and scattered it over the poorest part of the field....We had not yet heard of "wheat drills" but sowed our grain "broadcast." We would take a bag and tie the string to one corner so we could hang it about the neck...and carry...about a bushel of wheat in it. We would catch up handfuls and sow them broadcast having first marked out the field into "lands" of a proper width. A little practice enabled one to sow very evenly. We then dragged a heavy harrow over it. Now [in 1907] a man will do the same work in a better manner sitting in a pleasant seat driving two horses....

After mowing [the following summer] the wheat...was bound into sheaves and put in shocks of a dozen sheaves each. The children were nearly all, boys and girls, kept home from school to carry sheaves for shocking.....All the mechanics in the neighborhood worked in the harvest fields. The rule was, to pay them wages per day what wheat sold for per bushel. If wheat was worth a dollar per bushel, they got a dollar a day....

During the winter we "trod" out the wheat....we had a "treading floo" in the barn about 40 feet square. Many farmers' barns were not large enough for that, and they had what is called a "threshing floor" in the Bible: a level piece of ground, fifty or sixty or more feet in diameter, made smooth and packed hard....

We stacked our wheat as near the barn as we could, in the "stack yard," and when we commenced treading it out, we would take the sheaves into the barn, take off or loosed the bands, and lay a ring of sheaves four feet or four sheaves wide all around the floor. We laid the first one flat on the floor, the next one with the heads upon the butts of the first and so on all around the floor. We thus had a ring of sheaves about four feet wide, with the heads of the wheat only showing, and a vacant space in the middle of the floor, of about twenty feet in diameter.

We then put four horses, two abreast, walking around on the wheat, against the way the wheat pointed. After the horses had walked around sufficiently, two of us would each take a pitchfork, one on each side of the wheat, and turn it over. This we would repeat until the grain was all out of the straw, which was then raked off and stored as feed for the cows and steers during the winter....

Treading out wheat always made me feel as if I had a cold, headache, back-ache and slight fever, the result of the dust; and my grandmother used to say it always made me "take a bad cold."

When the wheat was all "trod," or when the floor became full, we cleaned it. We ran it through the wheat fan twice; the first time through the coarse riddle taking out the chaff only; the second time through the fine riddle taking out the "white caps" leaving only the clean wheat. The "white cap" was a grain of wheat with the chaff still fast on it. We then took it to the mill, where it was passed to our credit, to be drawn out for use or for market. We cleaned our wheat so well that it was never "docked" as that of some farmers was, that is, a number of pounds or bushels deduced, sufficient to make up for the refuse matter the wheat contained....

Farmers rarely if ever sold their wheat. They delivered it at the mill and got credit for it at the rate of sixty pounds to the bushel and when they wanted flour, they got for every sixty pounds of wheat, forty pounds of flour and about fifteen pounds of bran.¹

Questions for Reading 2

1. In what season was the wheat planted near Waterford? When was it harvested?

2. Who carried the sheaves for shocking?

3. What was the pay for a farm laborer's day of work in the 1820s in Virginia?

4. How might we describe today the "illness" Mr. Janney experienced while treading out wheat?

5. Did farmers get much money for their wheat? Explain your answer.

6. What does the reading indicate the miller might have received for his work?

¹Werner L. Janney and Asa Moore, editors, John Jay Janney's Virginia: An American Farm Lad's Life in the Early 19th Century (McLean, Va.: EPM Publications Inc., 1978), 72-75.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Waterford's Mill Ledger

Nathan Walker purchased the Waterford mill in 1848 from Thomas Phillips. He continued to record his accounts in Phillips's mill ledger. A Quaker, he did not believe in honoring Roman gods through the common names of the months, so he referred to the months by numbers. For example, "1st month" meant January and "6th month" meant June.

Of special interest is the variety of products produced by the mill. The plaster mentioned is ground limestone, which was spread on fields to improve the soil. A "cord" is a unit of measurement of firewood: 4' x 4' x 8' or 128 cubic feet.

Questions for Reading 3

1. The wheat that was planted, mowed, and threshed in Reading 2 has been ground into its finished product, flour, in this reading. Why is this flour being shipped out of Waterford?

2. How many barrels of flour were hauled to Point of Rocks from the 1st of January to the 20th of August, 1849?

3. Point of Rocks was a town not much larger than Waterford. Why did the people of Waterford haul flour 10 miles and ferry it across the Potomac River to Point of Rocks? (If needed, refer to Map 1.)

4. If three tons of plaster costs $3 to haul, and a "load of planks" costs $4 to haul, calculate the probable weight of a "load of planks."

5. If the hauling rate was $1 per ton, and it costs $4 to haul 20 barrels of flour, calculate the weight of a barrel of flour.

Reading 3 was compiled from the mill ledger of Thomas Phillips, courtesy of descendant Anne Stabler Parsons. Copies are available at Waterford Foundation Archives and Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia.

Visual Evidence

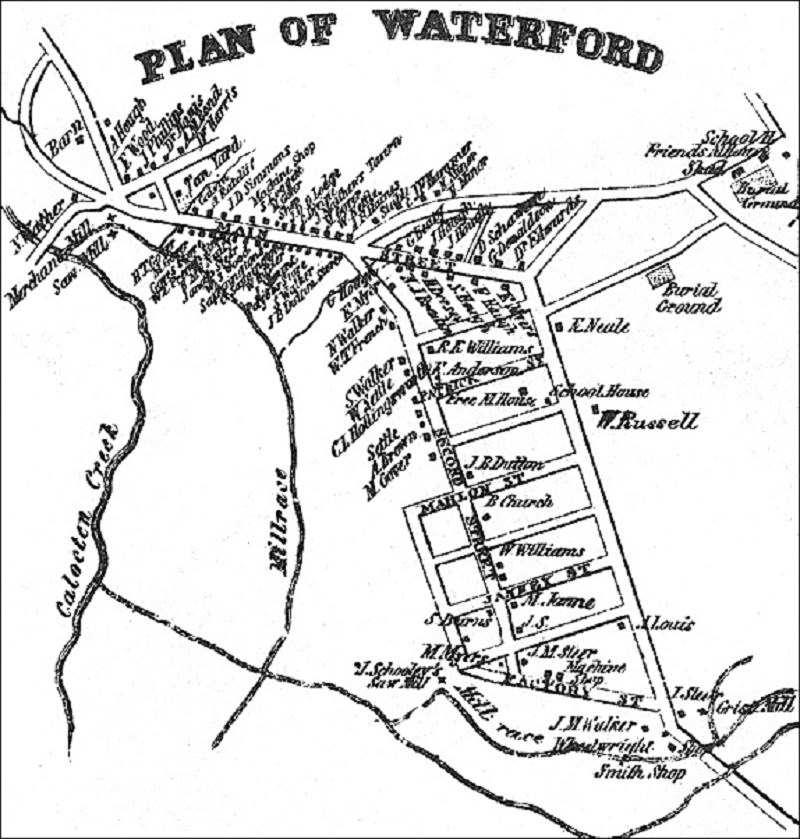

Drawing 1: Plan of Waterford, 1853.

This map, adapted from an 1853 Loudoun County map by Quaker historian Yardley Taylor, shows the names of Waterford's residents and the location of streets, mills, businesses, churches, and burial grounds.

Questions for Drawing 1

1. Name some of the businesses and churches you find on the map. Based on the plan and what you have learned in the readings, how would you describe Waterford in the 1850s?

2. Today Waterford has the same streets as it did in 1853. What does that indicate about change in the village?

Visual Evidence

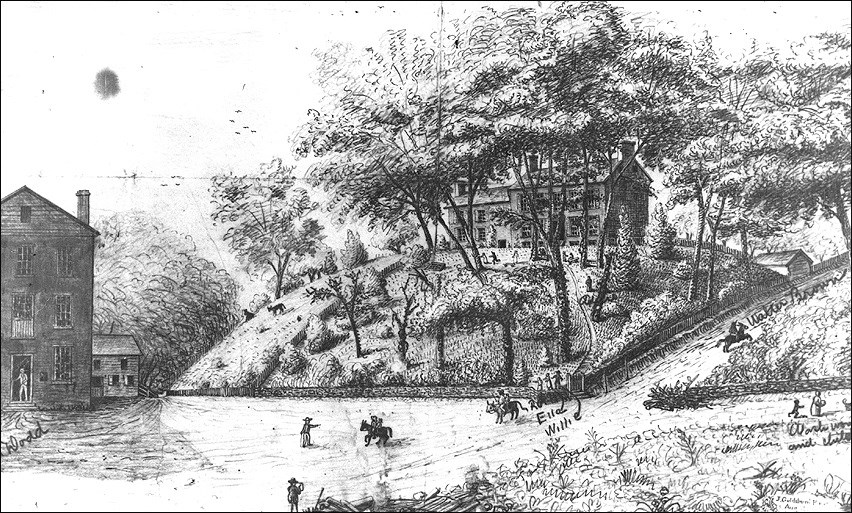

Drawing 2: Mill andmiller's house, lower Main Street, 1882.

(The Waterford Foundation)

Questions for Drawing 2

1. Locate this site on Drawing 1.

2. How would you describe the miller's house? Why would it have been built so close to the mill?

3. We do not know the name of the artist but do you think he/she came from Waterford? How do you know?

4. Does this drawing depict the log mill, the wood mill on a stone foundation, or the brick mill?

5. Based on this drawing, how did people get from one place to another during this time period?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: The Mill and miller's house today.

(Bronwen Souders)

The mill now belongs to the Waterford Foundation, and the miller's house, now called "Mill End," has been in private hands for many years.

Questions for Photo 1

1. Compare Photo 1 with Drawing 1. What are some of the changes that have taken place since 1882? What things have stayed the same?

Visual Evidence

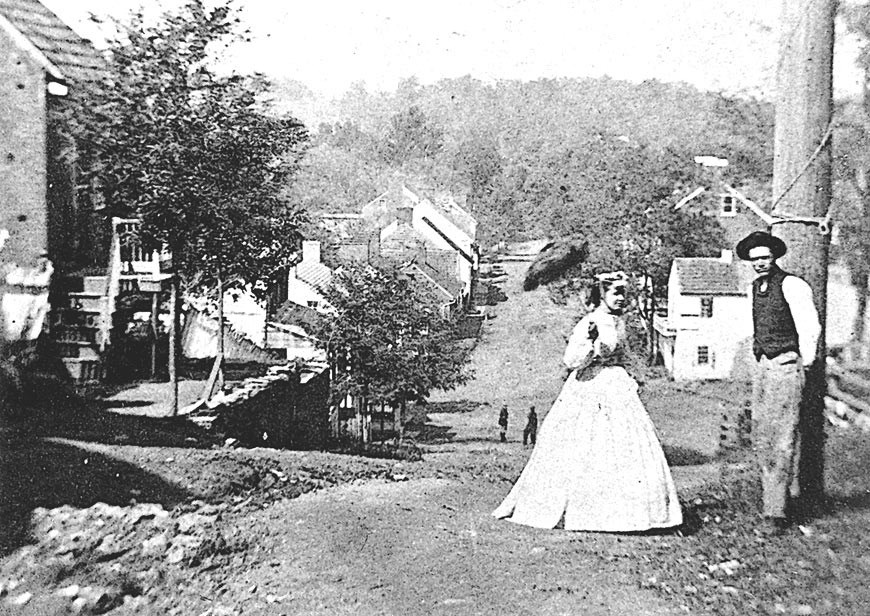

Photo 2: View down Main Street hill, circa 1862.

(The Waterford Foundation)

Photo 3: View down Main Street hill today.

(Bronwen Souders)

Photo 2 shows residents Annie Hough and brother Silas standing on Main Street. The Mill is down the hill at the far end of the street. Waterford today is little changed from this 19th-century view.

Questions for Photo 2 and Photo 3

1. Study both photographs. What are some of the similarities and differences between the two views?

2. What can you learn about the topography of Waterford by studying these photos?

3. Refer back to Drawing 1 and try to determine from where Photos 2 and 3 might have been taken.

4. What national event was happening in 1862?

5. Do you think it was unusual for Annie and Silas to have their picture taken at this time? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Quaker meeting house

Waterford's original Quaker meeting house was built in the 1740s from logs. In 1761, Waterford's Quakers replaced the original meeting house with the right half of this building. Ten years later, they doubled the size of the meeting house to 36 feet by 72 feet with the addition of the left side. Also evident in the photo is part of the cemetery for the meeting house. The building has been used as a residence since 1939.

Questions for Photo 4

1. Why would the first meeting house have been made of logs?

2. Which other buildings in Waterford started as log buildings?

3. What do the changes in size of the building say about the growth of the Quaker population in Waterford?

4. Why do you suppose the Meeting House is now a private residence?

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help students better understand continuity and change in Waterford as well as their own community.

Activity 1: A Step Back in Time

Remind students that Waterford today is little changed from the 19th or even the late 18th centuries, so even modern photographs can provide an idea of how Waterford used to be. Ask students to imagine that they lived in Waterford in the 19th century, and have them select one of the following activities:

a. Write a story about your experiences either helping with the wheat harvest or at the mill.

b. Draw three pictures of yourself while helping with the harvest or at the mill.

c. Make a model of the mill.

Activity 2: Waterford, Then and Now

Begin the activity by drawing two large overlapping circles on the blackboard. Label the overlapping area "C," and the two circles "A" and "B." Then ask the class to name some of the things they would find in Waterford if they visited about 1850. List these in Circle A.

Next, ask students to name things they would find in Waterford if they visited today. List these in Circle B.

Section C represents elements of the village common to A and B. With the students' help, draw an arrow to C from any element that appears in both Circle A and Circle B. For example, the mill was in Waterford in 1850, is still in Waterford today, and so should be included in section C.

To complete the activity, hold a classroom discussion about what the number of arrows indicates about how much or how little Waterford has changed over time.

Activity 3: Change over Time in Your Town

Remind students that just as Waterford began with settlers looking for new land who became such successful farmers they produced a local mill economy, their own town or neighborhood had a reason to begin.

1. Have students divide up into small groups and work with the library's local history materials or visit the local historical society to find out the following information, and then share it with the class.

a. When was your town founded?

b. Why was it founded?

c. What is the date of the oldest building that is still standing?

d. Is the building being used for the same purpose it had originally, or not? If applicable, does the building have its original name, or not?

e. What other institutions or resources, besides the library and a historical society, might have information on your community?

2. Divide students into teams to research the occupational history of your town or neighborhood. Either obtain for your students or coordinate with the local library or county historical society so students can look at several transcribed or microfilmed pages of the 1850, 1880, and 1930 censuses for your town or community. The 1930 census is the latest one available with names listed; if your neighborhood was founded after 1930, your county offices should have occupation data from more recent census on the residents that it can give you.

Ask each team to:

a. Compile a list of all the occupations of their parents, guardians, or local relatives.

b. Write down the names of the historic occupations for the census date or dates assigned to you for your area.

c. Compare the historic occupations with the current occupations listed by the class. What differences do you see? What similarities do you see?

d. Analyze the reasons why occupational change has taken place in the community or why change has not occurred.

Ask each team to share the information it has found in a class presentation that may include graphs and charts. Discuss as a class the changes from 1850 to 1880, and then to 1930, and finally to the present.

Waterford, Virginia: From Mill Town to National Historic Landmark--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Waterford, Virginia: From Mill Town to National Historic Landmark, students will learn about the life of a community over the period of more than 250 years. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Waterford Foundation

The Waterford Foundation's Web site is an excellent resource for information about Waterford. Included on the site is a virtual tour of the village and additional historical information about the community.

Library of Congress: Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS)/ Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Collection

Search the HABS/HAER collection for detailed drawings, photographs, and documentation from their architectural survey of Waterford, Virginia. HABS/HAER is a division of the National Park Service.

The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park

The C & O Canal NHP is a unit of the National Park System. The park's web pages provide a detailed history of the park.

The Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor

The Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor's Web pages include information about the Bristol Historic District, a Quaker community established in 1681 in Pennsylvania whose economic history contrasts with that of Waterford.

Last updated: March 30, 2023