How have National Parks changed over time?

Viewing photographs of different eras in the national parks can give many insights on ecosystem processes, as well as simply change over time. The panoramic lookout photographs provide a window on the past and an opportunity to compare to the present with changes to landforms and land cover.

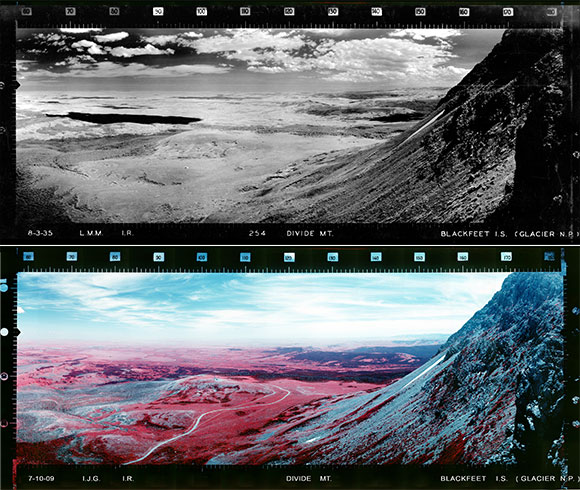

Glacier National Park's Divide Lookout in 1935 and 2009.

A Bit of History

In the early 1930s, the US Forest Service embarked on a panoramic photography project that used lookouts and lookout points to create maps for fire lookouts. In 1933, the first year that photography took place, the Civilian Conservation Corps provided the manpower for the project. The Forest Service focused their version of the project on the Pacific Northwest, the Forest Service’s Region 6.

In 1934, the National Park Service purchased an Osborne photo-recording transit identical to that used by the Forest Service to initiate a similar project and take panoramic photographs from lookout points as well. However, unlike the Forest Service, the National Park Service did not just focus on the Northwest, but rather photographed points from 200 lookout locations in the national parks all across the country. The main photographer for the National Park Service was one of the original participants in the US Forest Service project, Lester M. Moe.

At a time when the 10:00 a.m. policy reigned for both the US Forest Service and the National Park Service, the project’s purpose was one in the same for both agencies: to gauge distances and response times from lookouts and lookout points in order to put out wildfires quickly. The photographs were used in conjunction with an instrument found in lookouts called an Osborne fire finder. View a video about taking the past and comparing it to the future.

The Continuing Project

Fast-forward to the present and many of the photographs taken by Lester Moe still exist today in national park archives and museums. The care they’ve received over the years has varied, and some are becoming discolored and disintegrating.

A project more recently undertaken by the National Park Service Division of Fire and Aviation Management aims to preserve what is left of these 1930s photographs and digitize them. Gigapan, a website whose partners include NASA, Google, and Carnegie-Mellon University, has served as a host for these recently digitized images, as well as for images that have been taken in the same locations as part of a “retake” project.

In 2007, the National Park Service partnered with the US Forest Service to duplicate Moe’s images using the same photo-recording transit in Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. This retake project allows a close comparison over time to understand how change--both in landforms and land cover--has occurred over the past ¾ of a century.

How You Can Participate

Despite not having a photo-recording transit, anyone can participate in the retake project through the use of Gigapan’s technology. In this web section, learn more about the stories associated with panoramic photographs from NPS lookouts, as well as about citizen science opportunities to actually participate in the project.

You have an opportunity to be part of a story that began with the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s and is still relevant today, not only for the purposes of fire management, but also to understand how our national parks are changing in the 21st century.

Material for this section credited to Albert Arnst's article We Climbed the Highest Mountains.

Part of a series of articles titled Panoramic Project Shows How National Parks Change Over Time.

Last updated: July 22, 2020