Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user docprt – A visitor to Cabrillo, the Costa’s Hummingbird.

Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user docprt – A visitor to Cabrillo, the Costa’s Hummingbird.Native only to the Americas, there are over 350 different species of hummingbirds. Characterized by their small stature, long bills, and “humming noise” emitted by their ultra-fast wingbeats (on average 53 beats per second), these birds can actually be quite diverse. For instance, the world’s smallest bird, the Bee Hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae), can perch comfortably on top of a pencil eraser, whereas there is very little that is comfortable about the Sword-billed Hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera) – this little guy can’t even preen his feathers with his exaggerated beak and must use his foot, instead!

Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user wayne_fidler – The world’s tiniest bird, the Bee Hummingbird.

Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user wayne_fidler – The world’s tiniest bird, the Bee Hummingbird.  Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user nikitacoppisetti – The aptly-named Sword-billed Hummingbird.

Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user nikitacoppisetti – The aptly-named Sword-billed Hummingbird.For all of their differences, hummingbirds share some fascinating things in common. One of the most incredible characteristics of hummingbirds is how they fly. Hummingbirds are the only type of birds that can truly hover. Don’t let that raptor fool you – hawks, eagles, or vultures are only using air currents to make it appear that they’re hovering. Hummingbirds, on the other hand, do not require air currents as they hover by wing power alone. They can achieve this feat because of how their wings move. Hummingbirds do not move their wings in a linear forward-and-backward fashion as other birds do but, rather, in a figure eight. This advanced design allows the bird to hover and move in any direction, including backwards!

Photo courtesy of University of Texas at Austin – A top-view look of a hummingbird’s flight pattern while hovering.

Photo courtesy of University of Texas at Austin – A top-view look of a hummingbird’s flight pattern while hovering. Photo courtesy of University of Texas at Austin – A side-view look of a hummingbird’s flight pattern while hovering.

Photo courtesy of University of Texas at Austin – A side-view look of a hummingbird’s flight pattern while hovering.For many years, scientists believed that hummingbirds drank nectar through a process called capillary action, where liquid is passively drawn into a region. This is the same way that paper towels absorb water, for instance. Recently, this belief was debunked through high-speed imaging techniques and the truth is even stranger than what scientists first thought. It turns out that the structure of hummingbird tongues is responsible for their ability to lap up nectar – the tongue is split in two at the end, much like a snake’s. When a hummingbird sticks its tongue out, it compresses these ends into a flat surface with its beak – as the compressed ends come in contact with nectar, they spring back to their original, unflattened shape which traps the nectar inside. This process is repeated up to 18 times a second, the end result being the lapping of nectar much like a cat or a dog drinking water. Like a flower unfolding in the morning, then furling up again at end of day, a hummingbird’s tongue is continually changing shape in order to become the most effective tool for drinking nectar.

Hummingbirds are also known for their colorful, shiny feathers that are iridescent in sunlight. But many of these feathers appear boldly colorful, not because of the pigment that’s deposited in the structure, but because of how light hits the feather! Take the most common species of hummingbird in San Diego, the Anna’s Hummingbird (Calypte anna): males of this species flash a bright pink gorget (breast, chin, and head) when the light hits them just right – when the feathers are illuminated and viewed at a particular angle. Hummingbirds have feathers with several layers of pigments and the reflectance of light from these many layers results in a particularly bright flash of color.

Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user johndreynolds – A male Anna’s Hummingbird from the side.

Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user johndreynolds – A male Anna’s Hummingbird from the side. Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user johndreynolds – The same male Anna’s Hummingbird flashing its pink gorget as the light is reflected.

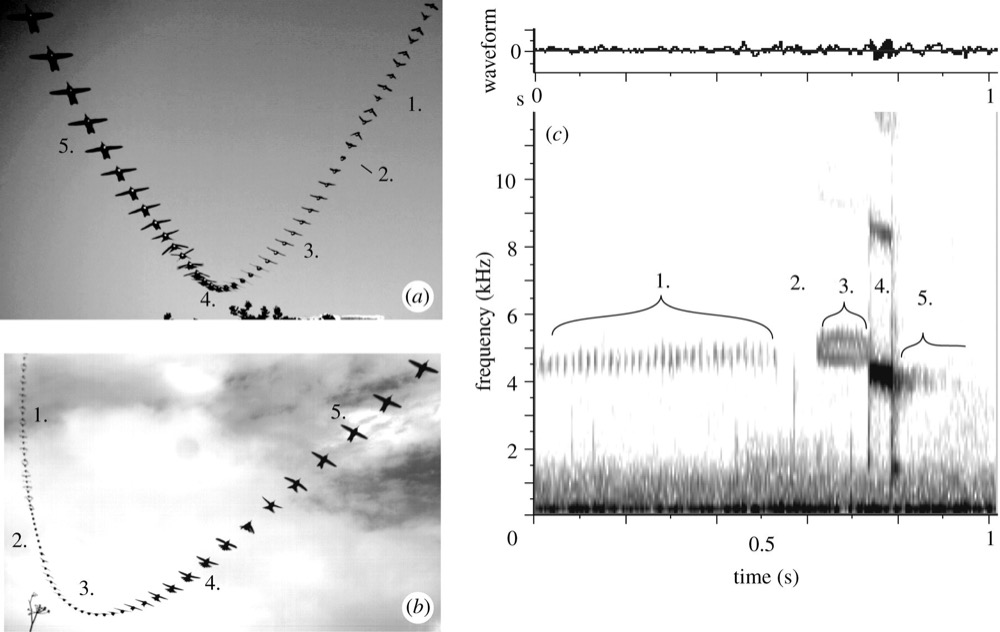

Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user johndreynolds – The same male Anna’s Hummingbird flashing its pink gorget as the light is reflected.Even the noises that hummingbirds make are unique. Like every species of bird, they have their own song, but not every bird can make a special and distinctive sound with its feathers! During the male-performed mating ritual called a “courtship dive”, many hummingbird species dive so quickly that the air passing through their tail feathers emits a pronounced squeak. The vibration of these feathers in a specific frequency is what makes the sound, called a “mechanical noise”. Different species have their own specific frequency and, thus, their own particular mechanical noise. Anna’s Hummingbirds, for example, emit a loud, uniform chirp while Allen’s Hummingbirds (Selasphorus sasin) display a quieter intermittent chirp.

Photo courtesy of Proceedings of the Royal Society B – A male Anna’s Hummingbird display dive as caught on high-speed video and sound recordings.

Photo courtesy of Proceedings of the Royal Society B – A male Anna’s Hummingbird display dive as caught on high-speed video and sound recordings. Here at Cabrillo National Monument, we regularly see five hummingbird species (Anna’s Hummingbirds, Allen’s Hummingbirds, Rufous Hummingbirds, Costa’s Hummingbirds, and Black-chinned Hummingbirds). This year they are particularly active at the park due to all of the rain, and thus, all of the blooms! So much nectar for these little guys to drink. So if you’re a hummingbird fan (like I am) make your way to the monument before all of these flowers fade and nature’s aerial acrobats move on.

Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user garth_harwood – A rusty-colored (rufous) Allen’s Hummingbird, one of the hummingbird species found at Cabrillo National Monument.

Photo courtesy of iNaturalist.org, user garth_harwood – A rusty-colored (rufous) Allen’s Hummingbird, one of the hummingbird species found at Cabrillo National Monument. References

For more on courtship dives:

https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2011/09/dive-bombing-hummingbirds-let-their-feathers-do-talking

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2009.0508

How hummingbirds drink:

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/11/hummingbird-tongues/546992/

For more on hummingbird flight:

http://design.ae.utexas.edu/humm_mav/theory.html