Photo Courtesy of Newsweek – the western edge of the Thomas Fire as seen from the shores of Santa Barbara in December 2017.

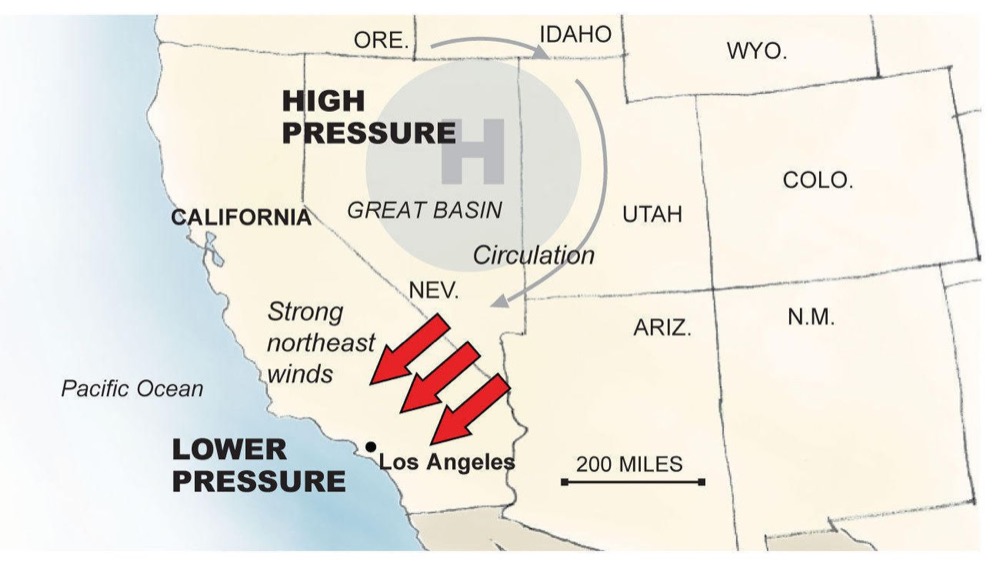

Photo Courtesy of Newsweek – the western edge of the Thomas Fire as seen from the shores of Santa Barbara in December 2017.Southern California is the perfect place for wildfires for a few reasons, namely the climate. This region has what is known as a Mediterranean Climate, which is characterized by a short rainy season and a long, hot, dry summer. By this time of year, plants haven’t seen water since about March. They’re extremely dry and could ignite with the smallest spark. And though natural ignitions (lightning) are rare, there’s millions of people here to make up for that with careless mistakes. But the dry heat isn’t necessarily what makes these fires so destructive; that can be attributed to the Santa Ana Winds. The Santa Ana’s are caused when there’s a high-pressure system in the Great Basin area and a low-pressure system in Southern California. As the air travels from high to low pressure, great winds blow from east to west, reaching over 100 miles per hour in some areas. When fires burn during the Santa Ana’s, embers fly, and the fire quickly grows out of control.

Photo Courtesy of the LA Times – a map showing the high- and low-pressure systems that lead to the Santa Ana Winds.

Photo Courtesy of the LA Times – a map showing the high- and low-pressure systems that lead to the Santa Ana Winds. Photo Courtesy of NASA – a satellite image of smoke being blown offshore from multiple fires burning in Southern California and Baja Mexico.

Photo Courtesy of NASA – a satellite image of smoke being blown offshore from multiple fires burning in Southern California and Baja Mexico.Ninety-five percent of all California fires occur in the chaparral plant community, the dominate community in Southern California. When fires burn in chaparral, they’re called “crown fires” because the community is destroyed completely – all the plants are burned to the ground. However, many plants in the chaparral community are adapted for fire; some even need it to survive. Many plants have thick, waxy leaves that don’t burn easily, or widespread underground roots that allow them to regrow next season. Some plants even have hard coats around their seeds that must be melted away by fire in order to germinate. Fires can also eliminate dead or invasive plants from the area, clearing the way for new native vegetation to grow.

NPS Photo/Keith Lombardo – an example of the chaparral ecosystem as seen from the Bayside Trail at Cabrillo National Monument.

NPS Photo/Keith Lombardo – an example of the chaparral ecosystem as seen from the Bayside Trail at Cabrillo National Monument.With all of this in mind, Dr. Keith Lombardo set out to study Southern California fires while at the University of Arizona about 10 years ago. He wanted to determine whether these large, destructive fires have always been happening, or if events like the Thomas Fire are a new norm. To answer this question, he needed a lot of data reaching back hundreds of years. Agencies such as CalFire have kept accurate records of every fire in California since about 1900, but that wasn’t good enough. Instead, Dr. Lombardo turned to tree rings. It’s relatively common knowledge that one can determine the age of a tree based on the number of rings its trunk has, which is true. However, tree rings also keep a record of events in the ecosystem – a larger distance between two rings, for example, might indicate a wet year, where the tree grew a lot. Additionally, trees typically don’t burn all the way to the ground the way the chaparral does in a crown fire, but the flames do leave scars. Looking at the tree rings in this way, scientists can determine with about 90% accuracy exactly when a fire occurred.

NPS Photo/Keith Lombardo – an example of a tree ring record used to study wildfires. This trunk shows evidence of fire in the years 1696, 1705, 1708, 1715, 1730, and more that are cut off in the photo.

NPS Photo/Keith Lombardo – an example of a tree ring record used to study wildfires. This trunk shows evidence of fire in the years 1696, 1705, 1708, 1715, 1730, and more that are cut off in the photo.For his research, Dr. Lombardo sampled hundreds of Bigcone Douglas Fir trees throughout the Los Padres, Angeles, and San Bernardino Forests. These trees occur in small groves scattered throughout the chaparral, so it’s easy to assume that if a flame affected the trees, it affected the surrounding chaparral, as well. Looking at all of this data, which dated back to the 1600s, Dr. Lombardo concluded that large-scale fires have always been a part of the Southern California landscape. The biggest difference between fires then and now is how they’re started – as human population has increased, so have human-caused ignitions.

NPS Photo/Adam Taylor – photo taken just after an area of chaparral burned during the Cranston Fire outside of Idyllwild, CA in July 2018.

NPS Photo/Adam Taylor – photo taken just after an area of chaparral burned during the Cranston Fire outside of Idyllwild, CA in July 2018.So, what does this all mean? This research poses some questions about how we should manage fires and our communities. If wildfires are a part of this ecosystem, should we just let some of them burn? If we let more small fires burn freely, will the system self-regulate, creating ecosystems with a mixture of new and old plant growth? Where should we build our homes, and how should we build them? How do we build more resilient communities? Should we continue to live in fear of wildfire, or learn to coexist with it?

NPS Photo/Adam Taylor – a fire crew gets dropped off by helicopter during the Cranston Fire outside of Idyllwild, CA in July 2018.

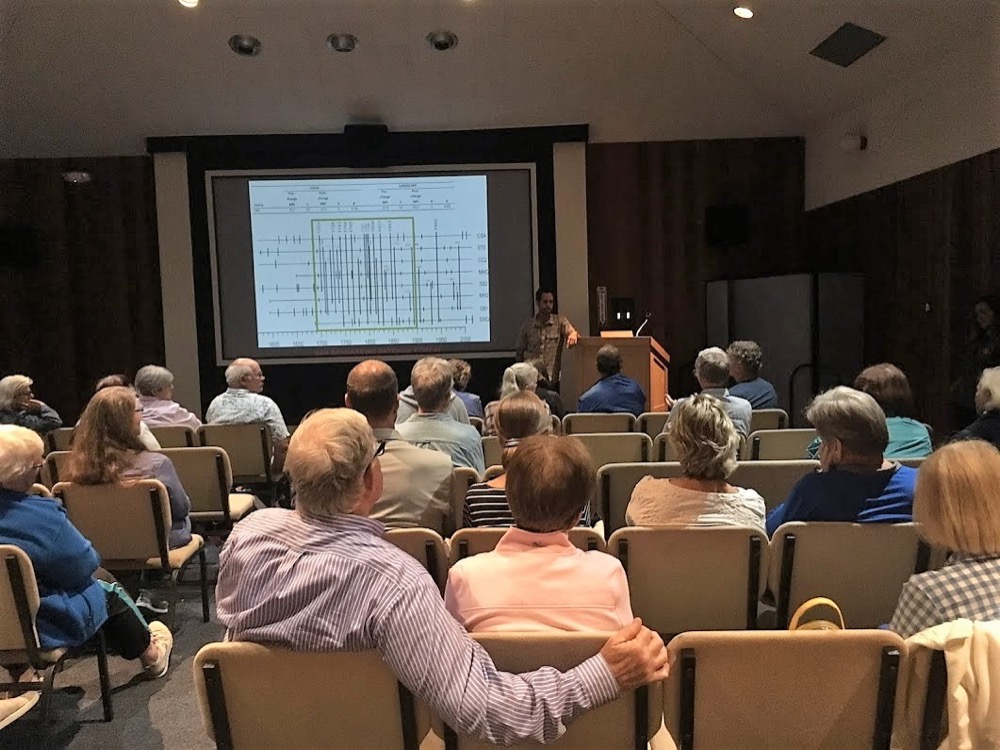

NPS Photo/Adam Taylor – a fire crew gets dropped off by helicopter during the Cranston Fire outside of Idyllwild, CA in July 2018.*A special thank-you to Dr. Keith Lombardo for his fantastic lecture on September 20. If you would like to become a Foundation member and attend future members-only events, visit the CNMF website at: https://cnmf.org/shop/membership/

**Stay tuned for our next round of Naturally Speaking Science Education Lectures, coming soon!

NPS Photo/McKenna Pace – CNMF members and Volunteers enjoy Dr. Keith Lombardo’s Naturally Speaking lecture on September 20 in the Cabrillo National Monument Auditorium.

NPS Photo/McKenna Pace – CNMF members and Volunteers enjoy Dr. Keith Lombardo’s Naturally Speaking lecture on September 20 in the Cabrillo National Monument Auditorium.