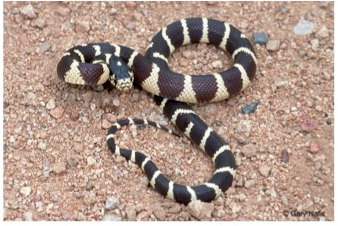

NPS Photo /Gary Naris – One version of the California Kingsnake – they can also come in brown & cream markings or with longitudinal stripes

NPS Photo/Gary Naris – The most common lizard at CNM, often referred to as “blue bellied” lizards

NPS Photo /Gary Naris – The only amphibian species found at CNM and very rarely seen in this dry climate

Because these species are important to the ecosystems of Cabrillo National Monument, park scientists have been monitoring their populations since 1995. Herpetofauna monitoring consists of recording life data from a sample of captured herps. Two methods are used for capturing the animals – the pitfall trap and snake trap. The pitfall trap is an open bucket buried level with the ground, while a snake trap consists of a tube made of chicken wire with contraptions placed at either end that prevent the snake from escaping. Fifteen meters of drift fences guide the herps toward each trap (see array photo). Once a month, 18 different arrays of traps spread across the Monument and neighboring Navy land are opened up for a week and checked daily for captured animals. Every captured herp is weighed, measured, and sexed (if possible). Notes about the organism’s general condition are also taken, such as whether the herp has a mite infestation. These data are recorded and entered into a database to track populations over time. By taking a random sample (those captured each month) of the local herp populations, trends can be extrapolated for the entire resident population.

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – A trap array with fencing that guides herps to a pitfall or snake trap

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – A trap array with fencing that guides herps to a pitfall or snake trap NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – A close-up shot of a trap array

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – A close-up shot of a trap array  NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – This tube made of chicken wire with cones clipped to the ends traps snakes humanely inside

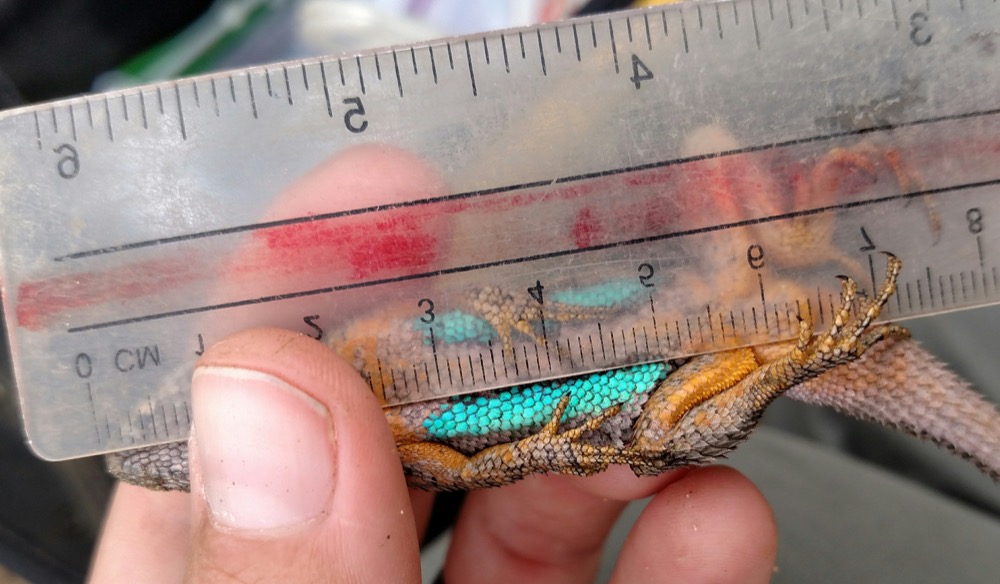

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – This tube made of chicken wire with cones clipped to the ends traps snakes humanely inside NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – The torso of a Great Basin Fence Lizard (Sceloporus occidentals longipes) being measured

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – The torso of a Great Basin Fence Lizard (Sceloporus occidentals longipes) being measured

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – Placing a Great Basin Fence Lizard (Sceloporus occidentals longipes) in a bag and subtracting the bag’s weight from the total is an easy method to discerning the weight of a squirmy lizard

Said trends can include growth or decline in population size, biogeography (where animals live), sex ratio (how many males and females exist in the population), and population averages such as mass. Population statistics are useful to scientists in assessing how healthy a population is, and whether it is under any pressure or affected by stressors such as urbanization, habitat fragmentation, and climate change. Park scientists are currently analyzing the collective data – stay tuned for the results!

Note: These animals are handled safely by trained wildlife professionals and in accordance with Federal regulation.

Additional Information

The herps of Cabrillo National Monument:

https://vipvoice.wordpress.com/reptiles-and-amphibians-at-cnm/

https://vipvoice.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/reptile_bulletin.pdf

Everything about herps in California:

http://www.californiaherps.com/