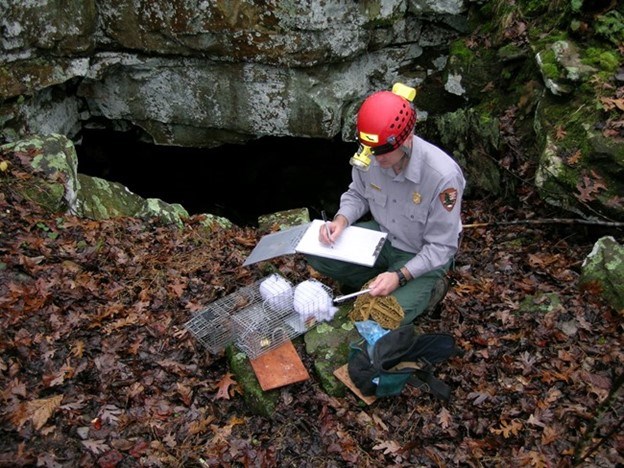

NPS photo Carved by wind and water, Cumberland Gap forms a major break in the Appalachian Mountain chain. Stretching for 26 miles along Cumberland Mountain and ranging from 1 to 4 miles in width, the park contains 24,000 acres, of which 14,000 acres is recommended wilderness. The natural beauty of Appalachian Mountain country, lush with vegetation, supports diverse animal life, including white-tailed deer, black bear, rabbit, raccoon, opossum, gray squirrel, fox, and wild turkey. Park resources provide habitat for two federally endangered species, the Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) and the northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis), and two federally threatened species, the blackside dace (Phoxinus cumberlandensis) and the white fringeless orchid (Platanthera integrilabia). Natural resource inventories of amphibians, birds, fish, mammals, reptiles, and plants completed in the early 2000s documented 1,212 types of organisms in the park. More than 130 of these are considered rare. The majority of the park's forest is a second- and third-growth Eastern hardwood and conifer mix, the result of timbering and farming over a 175-year period. The park protects more than 30 known entries to limestone caves, the best known of which is Gap Cave. Other significant natural features include the Pinnacle, Sand Cave, and White Rocks.

NPS photo Scientific research is key to protecting the natural and cultural wonders of our national parks. To make sound decisions, park managers need accurate information about the resources in their care. They also need to know how park ecosystems change over time, and what amount of change is normal. But park staff can’t do it alone. Like a physician monitoring a patient's heartbeat and blood pressure, scientists with the Cumberland Piedmont Network collect long-term data on Cumberland Gap’s “vital signs.” They monitor key resources, like cave animals and meteorological conditions, forest vegetation, and water quality. Then they analyze the results and report them to park managers. Knowing how key resources are changing can provide managers with early warning of potential problems. It can also help them to make better decisions and plan more effectively. But studying park vital signs is only part of the picture. Scientific research is also conducted by park staff, other state and federal scientists, university professors and students, and independent researchers. Because many parks prohibit activities that occur elsewhere, scientists can use the parks as areas for determining the effects of these activities where they do occur. National park lands often serve as the best model for what a relatively undisturbed landscape looks like. You can learn about recent research or generate a park species list below.

|

Quick ReadsSource: NPS DataStore Saved Search 5539 (results presented are a subset). To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore. Park Species ListsSelect a Park:Select a Species Category (optional):

Search results will be displayed here.

|

Last updated: February 27, 2024