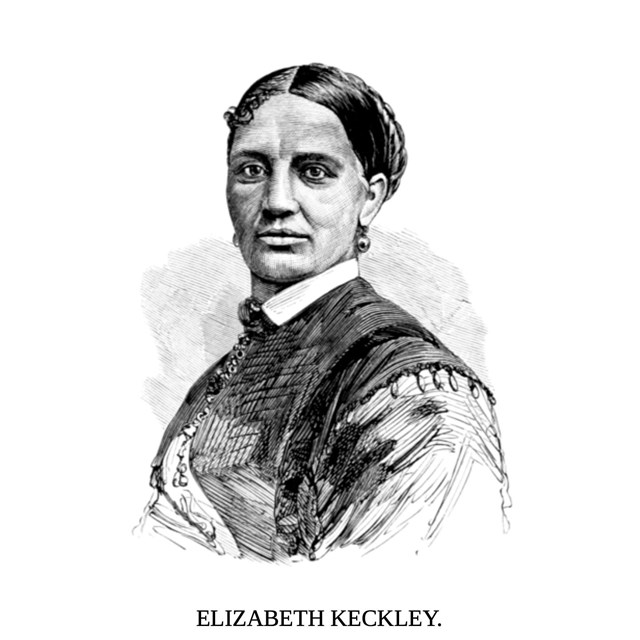

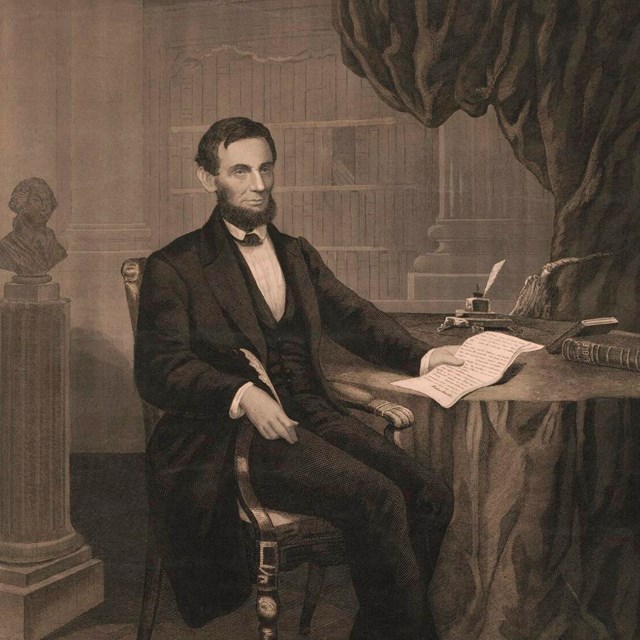

Library of Congress Mary Todd Lincoln (1818-1882) was born into an influential and politically well-connected Kentucky family in Lexington. The Todds were among a handful of elite families in the state that sought to create a citadel of civilization on the frontier. Mary’s upbringing reflected these values. The family, who played an integral role in the creation of Transylvania University, made sure that Mary received a solid education. Rare among women of her time, Mary Todd attained nearly ten years of schooling. She followed six years of study at Shelby Female Academy with four more years at Madame Charlotte Mentelle’s boarding school. By that point, she had become fluent in French. Mary's academic background instilled a poise in her that would become one of the hallmark characteristics of her personality. At age fourteen, she dined alongside close family friend and presidential candidate Henry Clay. Mary told Clay that she, too, fully expected to live in Washington in the future. Abraham Lincoln considered Henry Clay a political idol. It was only following his marriage to Mary Todd, though, that he had an opportunity to meet Clay in person. It came at a political meeting organized by Mary’s father in Lexington, while Lincoln was in route to Washington as congressman-elect in 1847. Socio-economically, Abraham and Mary were of two different worlds. Both, however, found a shared interest in politics and intellectual pursuits. Their mutual attraction to one another likely sprang from this mental connection. The two were also shaped by slavery. Abraham Lincoln got back into politics in the 1850s as the debate over slavery intensified. In Mary’s case, she experienced the institution firsthand, as the Todds were slaveholders. This background—and the enlistment of some of the Todds in the Confederate Army—fueled speculation that Mary was secretly sympathetic to the South during the war. The Todds, however, remained divided over the issue of slavery. Mary was among the Todds that opposed the institution. Throughout the Civil War, Mary Lincoln demonstrated concern for freedmen. She cultivated close personal relationships with African American women such as Elizabeth Keckly. Mary gave money and gifts to the burgeoning "freedom villages," where fugitive slaves sought refuge in and around Washington. She encouraged her husband to do the same.

Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana, Mississippi State University Libraries Mary Lincoln’s projects to refurbish the White House created a headache for Abraham Lincoln. In fairness, previous administrations had not spent much on the upkeep of the “Executive Mansion.” Many of the rooms had taken on a threadbare and shabby appearance. Mary’s zeal for furnishing the White House with more up-to-date décor, though, garnered unwelcome attention. This exposed the Lincolns to ridicule in the press and from the public. Her trips north to survey potential new materials for the White House ran from two to four months long and were costly. Abraham Lincoln covered some of these expenses out of his own pocket. Congress, too, eventually authorized two additional expenditures to cover part of Mary’s purchases. The Civil War took a toll on Lincoln’s presidency and the relationship between Mary and Abraham. In the days and hours before the fateful assassination at Ford’s Theatre, the two showed a renewed intimacy. Before their evening engagement at Ford’s, the Lincolns took a carriage ride together through Washington, DC. Opening up to Mary that day, Abraham acknowledged that “between the war and the loss of our darling Willie—we have both been very miserable.” They turned to talk about the future as they rode along. Abraham Lincoln talked of plans to voyage abroad to Europe, and even to travel out to the Pacific Coast to see California. These hopes would be tragically cut short.

Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection Mary's life was forever altered by the death of her husband. She wore the traditional Victorian mourning garb for the rest of her life, long beyond what social customs dictated. She fell under the influence of the spiritualist movement of the era, participating in many seances to attempt to contact her lost loved ones. Many unscrupulous con artists took advantage of the former first lady, such as the "spirit photographer" William Mumler. Mumler claimed that he could capture an image of Abraham Lincoln's ghost with Mary, but the photograph was a hoax. She lost another son in 1871, as young Tad died of tuberculosis. In 1875, as Mary's mental health declined, her lone surviving son Robert committed her to an insane asylum. She was released a few months later, living the rest of her life with her sister's family in Springfield. Mary Lincoln died of a stroke on July 15, 1882. Mary has been harshly evaluated by many writers over the years. In recent decades, more nuanced portrayals of Mary Lincoln have emerged. Both Lincolns suffered greatly following the deaths of their children, Eddie and Willie. Mary, in particular, was never quite the same again following the deaths of her two sons. It is clear the strictures of 19th century American society, and the very public role of first lady in this era, played a major role. Mary did not get the time and space to grieve in the way modern first families might be allowed. She could be strong-willed, mercurial, and outspoken. These traits were not appreciated in the period in which she lived. The added weight of the death of Abraham Lincoln on April 15, 1865, and those of her boys over the years, were immense burdens on Mary. The complexity of the relationship between Abraham and Mary Lincoln continues to intrigue the public. The partnership between the two shaped a political career and influenced the course of the Civil War. Focusing too much on Mary's shortcomings obscures an opportunity for us to assess what the two saw in each other. As Lincoln historian Kenneth J. Winkle aptly writes of Abraham and Mary, “. . . what a fascinating and enigmatic marriage they forged in undertaking it.” Want to Learn More?

|

Last updated: December 31, 2024