Library of Congress In the two weeks following the assassination of President Lincoln, federal agents worked to determine who was responsible for the heinous crime. Hundreds of people were detained, questioned, and in some cases imprisoned. The investigators settled on ten individuals they believed were responsible for the assassination. One, John Wilkes Booth himself, was cornered and killed at the Garrett farm in Virginia on April 26, 1865. Another, John Surratt, had fled the country. He did not stand trial until 1867. The remaining eight were charged in the conspiracy and tried by a military tribunal. Six of the eight had their pictures taken by photographer Alexander Gardner during this time. Gardner took the images aboard the ironclad ship USS Montauk, where the conspirators were imprisoned, to document their appearances. The trial lasted for seven weeks as 366 witnesses gave testimony. At the conclusion, four of the accused were sentenced to death by hanging. The other four were imprisoned. Mudd, Arnold, and O'Laughlen received life sentences of hard labor. Ned Spangler received a sentence of six years' hard labor. Authorities questioned several others who may have assisted Booth in the plot or in his escape. Many people were released due to a lack of evidence against them.

Library of Congress Samuel Bland Arnold (1834-1906)Samuel Arnold was a childhood friend of John Wilkes Booth. The two had been schoolmates at St. Timothy's School in Catonsville, MD in the 1850s. Arnold was a veteran of the Confederate army who was discharged due to illness. Booth recruited him to participate in the kidnapping plot in 1864. Arnold parted ways with Booth on March 15, 1865, following an argument in which he told Booth that his kidnapping plans were impractical. Arnold was not in Washington, DC at the time of the assassination. He likely did not have any knowledge of the plot to murder the president. Authorities arrested Arnold at Fortress Monroe, Virginia on the morning of April 17, 1865. Investigators quickly tied him to Booth and the kidnapping scheme. Arnold was tried and convicted of conspiracy to kidnap the president. He was sentenced to life in prison at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas off the Gulf Coast of Florida. Pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in 1869, Arnold lived until 1906. He published a memoir in 1902 that he hoped would vindicate his name. He is buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, the same final resting place as John Wilkes Booth and Michael O'Laughlen.

Library of Congress George A. Atzerodt (1835-1865)The German-born Atzerodt was a carriage painter and boatman. He had often ferried Confederate spies and supplies across the Potomac River between Maryland and Virginia. Booth recruited Atzerodt for his knowledge of the waterways and his ability to handle a boat. Both would be useful skills for transporting a kidnapped President Lincoln to Richmond. After Booth's plans changed from kidnapping to murder, he assigned Atzerodt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson. Johnson was staying at the Kirkwood House Hotel, a few blocks from Ford's Theatre. Atzerodt lost his nerve, drinking heavily at the hotel's bar and wandering the streets of the city through the night. Atzerodt fled Washington and was arrested on April 20, apprehended at the house of his cousin Hartman Richter in Germantown, MD. Atzerodt was tried and convicted for conspiracy to commit murder. He was executed by hanging on July 7, 1865. He is buried in an unmarked grave at Glenwood Cemetery, Washington, DC.

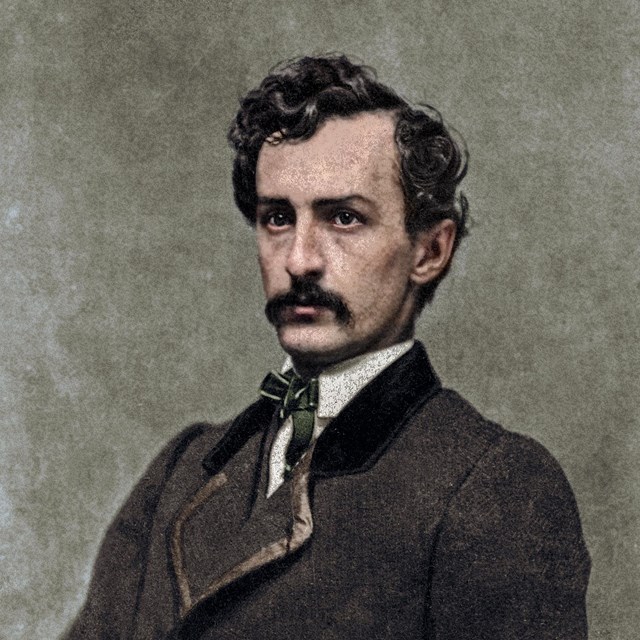

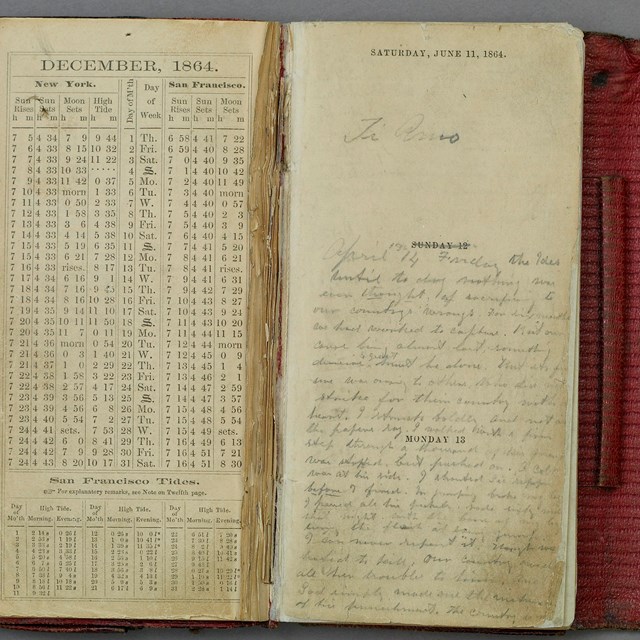

Library of Congress John Wilkes Booth (1838-1865)Before April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth was best known as a famous actor from a renowned theatrical family. His father, Junius Brutus Booth, and two of his brothers, Junius Jr. and Edwin, were also acclaimed performers. John Wilkes Booth wanted the Confederacy to win the American Civil War. He believed in the righteousness of slavery and of white supremacy. Booth saw Abraham Lincoln as a tyrant, destroying the societal structure of the South through war and emancipation. In 1864, he began assembling a ring of conspirators with the goal of kidnapping the president. He and his men would bring Lincoln to Richmond to turn the war in the Confederacy's favor. Though he plotted for several months, Booth's kidnapping scheme never came to fruition. With the Civil War reaching its end in April 1865, John Wilkes Booth decided that kidnapping Lincoln was no longer good enough. On April 14, he learned that the president would be attending that evening's production of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre. He reassembled his conspirators and shared with them his new plan to murder Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William Seward that evening. Booth shot President Lincoln in the back of the head during the play at about 10:15 pm. He jumped onto the stage and yelled "Sic Semper Tyrannis," Latin for "Thus always to tyrants," at the audience. This stated his belief that he had eliminated the American Julius Caesar. Booth escaped the theatre, heading on the run for the next twelve days with his fellow conspirator David Herold. The two were tracked down by Federal forces on April 26, 1865 at the Richard Garrett farm in Virginia. Booth refused to surrender and was ultimately shot dead by a Union soldier. Booth's body was initially buried in secret by the federal government. His remains were returned to the Booth family in 1869. The assassin now rests in an unmarked section of the Booth family plot at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland.

Library of Congress David E. Herold (1842-1865)David Herold first met Booth in 1863 after a performance at Ford's Theatre. Herold was friends with George Atzerodt and John Surratt and met Michael O'Laughlen through Atzerodt. His role in the assassination plot was to guide Powell to Secretary of State Seward’s home, then aid his escape out of the city. He fled after hearing the screams coming from the Seward home following Powell's attack. He met up with Booth in Maryland and stayed with Booth until his capture at Garrett's farm. Union authorities brought Herold back to Washington, DC. for trial. During the trial, Herold's lawyers described him as dull-witted and simple-minded. They attempted to convince the court that he was easily duped by Booth and should not be held responsible for his role. Herold had actually studied pharmacy at Georgetown and worked as a druggist's assistant. His answers to an interrogator suggested a quick and agile mind. David Herold was convicted and hanged July 7, 1865. He is buried in Congressional Cemetery, Washington, DC. His gravesite is marked only by the tombstone of his sister, buried beside him.

State Library and Archives of Florida Dr. Samuel Alexander Mudd (1833-1883)Mudd was a graduate of St. John's College and Georgetown College (now University). He earned his medical degree from the Baltimore Medical College in 1856. Dr. Mudd and his wife Sarah had 4 children. They lived on a 200+ acre tobacco plantation near Bryantown, Maryland, named Oak Hill, that had been in the Mudd family for seven generations. He met Booth on several occasions in late 1864 and early 1865. His home may have been a planned safe house for the Lincoln kidnapping plot. Booth and Herold arrived at Dr. Mudd's farm at about 4 am on April 15, seeking medical help for Booth's broken leg. Doctor Mudd treated the leg and made a splint for the assassin. He allowed Booth and Herold to rest in an upstairs room for several hours. Booth and Herold left Dr. Mudd’s the next afternoon, heading into the Zekiah Swamp and towards the Potomac River. Mudd later insisted that he did not recognize Booth and that he did not know that Lincoln had been assassinated. He was evasive and nervous when questioned. Dr. Mudd was tried and convicted of conspiring to kill the president. He was given a life sentence of hard labor at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, Florida. During an 1867 outbreak of yellow fever, Mudd provided medical care and helped save the lives of soldiers and prisoners. President Andrew Johnson pardoned him in 1869. He lived the rest of his life at his farm and fathered five more children. Dr. Mudd died January 10, 1883 at the age of 49. He is buried in the cemetery at Saint Mary's Catholic Church in Bryantown, Maryland.

Library of Congress Michael O'Laughlen (1840-1867)O'Laughlen was a childhood friend of John Wilkes Booth, living across the street from the Booth family in Baltimore. A former Confederate soldier, he was one of Booth's earliest recruits, joining the plot to kidnap the president in the fall of 1864. At trial, he admitted to participating in the failed abduction of Lincoln on March 17, 1865. He claimed that he withdrew from other abduction attempts when it seemed that Booth's plans were unreasonable. He likely did not have any role in the assassination plot. O'Laughlen turned himself in to authorities on April 17, 1865. He was tried as a conspirator and sentenced to life in prison. Sent to Fort Jefferson in the Florida Keys, he died there of yellow fever in 1867. He is buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, the same cemetery as John Wilkes Booth and Samuel Arnold.

Library of Congress Lewis Thornton Powell (alias "Lewis Paine") (1844-1865)Powell was a former Confederate soldier with the 2nd Florida Infantry who was wounded and captured at the Battle of Gettysburg. After recovering from his wounds, he escaped and joined Mosby’s Rangers in Virginia. Powell met John Wilkes Booth through John Surratt in January 1865. He soon became an important part of Booth's plan to kidnap President Lincoln. He used the aliases "Paine" or "Payne" so that his family would not find out about his role in the kidnap or murder if he was killed in the attempts. Tall and strong, he brought the muscle for the kidnapping. When Booth turned to murder, he assigned Powell to kill Secretary of State William Seward. Powell entered the Secretary's home in Lafayette Square and stabbed Seward and others in the house. After fleeing the Seward home, he found that he was alone and lost. He wandered the streets of Washington for three days before returning to the Surratt boarding house. When he arrived, detectives were arresting the occupants of the boarding house, and he was taken into custody as well. Powell was tried and convicted of conspiracy to assassinate the president. He was executed by hanging on July 7, 1865. His body is now located in a mass grave at Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington. His skull, which was somehow separated from his body, was discovered among the Smithsonian Institution's Native American skulls collection in 1991. The skull was returned to one of his descendants and buried in the family cemetery plot in Geneva, Florida.

Library of Congress Edman "Ned" Spangler (1825-1875)Spangler was a stagehand and carpenter at Ford's Theatre. He had met John Wilkes Booth years earlier while doing carpentry work on the Booth home, Tudor Hall, in Bel Air, Maryland. Spangler renewed their friendship while both were working at Ford's. Booth asked Spangler to hold his horse in the back alley behind Ford's the night of the assassination. Spangler turned that duty over to a young theater jack-of-all-trades, "Peanut John" Burrows. It is unlikely that Spangler knew anything about Booth's plots or intent. Even so, the military tribunal ruled him guilty of helping Lincoln's assassin escape. Spangler was sentenced to six years of hard labor at Fort Jefferson Prison in the Dry Tortugas, Florida. He became friends with Dr. Samuel Mudd while in prison. When both were pardoned by President Johnson in 1869, Spangler moved to Maryland and did odd jobs around the Mudd farm until his death in 1875. Spangler is buried in St. Peter's Cemetery in Waldorf, Maryland.

Library of Congress John Harrison Surratt, Jr. (1844-1916)John Surratt was one of Booth's most valuable and capable conspirators. He was a Confederate spy with a college education who ran mail and correspondence across Union lines. He also had contacts with Confederate Secret Service agents in Canada. Surratt introduced David Herold and George Atzerodt to Booth. He also brought Lewis Powell into Booth's orbit. The tavern in Maryland and boarding house in Washington owned by his mother, Mary Surratt, served as safe houses and planning locations for Booth and his conspirators. John Surratt took part in the failed abduction attempt on Abraham Lincoln in March, 1865. He was in Elmira, New York at the time of the assassination, scouting a prisoner-of-war camp there. Surratt fled to Canada, then England, when he heard news of the great crime. He lived as a fugitive for over a year, including serving under a pseudonym with the Papal Guards at the Vatican. In 1866, he was recognized and escaped again to Egypt, where he was finally apprehended. Extradited back to the United States, he faced trial by a civilian court in 1867. The case resulted in a hung jury. John Surratt was set free and never tried again. He began a lecture tour on his role in the kidnapping plot in 1870. Public outrage at this brazenness quickly led to the tour's cancellation. John Surratt died in 1916, the last surviving Lincoln conspirator. Many blamed him for his mother’s death, believing that had he surrendered himself in 1865, he would have been hanged in place of his mother. He is buried in New Cathedral Cemetery, Baltimore, Maryland.

Mary Elizabeth Surratt (née Jenkins) (1820 or 1823-1865)Mary Surratt was a Confederate sympathizer and widower in 1865. Her son, John Surratt, Jr., was a key member of John Wilkes Booth's conspiracy. Mrs. Surratt owned two important properties: a tavern in Maryland and a boarding house in downtown Washington, DC. Booth and his conspirators often met at the boarding house to plan the kidnapping, and eventually the assassination, of Abraham Lincoln. President Andrew Johnson called Mrs. Surratt's boarding house “the nest that hatched the egg.” Both Lewis Powell and George Atzerodt also boarded there briefly. Following the assassination, John Wilkes Booth and David Herold stopped for supplies at the Surratt Tavern in Surrattsville (now Clinton), Maryland. They met John M. Lloyd, who was leasing the tavern from Mrs. Surratt. Earlier on the day of the assassination, she rode down to the tavern and handed Lloyd a package that Booth had given her earlier that morning. According to Lloyd, she asked him to “have those shooting irons ready,” referring to guns hidden behind a false wall of the tavern. Due mainly to Lloyd's testimony, she received the death sentence for conspiring to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. Five members of the military tribunal asked that President Johnson grant her clemency on account of her age and sex. Johnson denied their request. Mary Surratt died by hanging on July 7, 1865. She was the first woman executed by the federal government in the United States. Her guilt or innocence, and the appropriateness of her death sentence, has been much debated by historians. She is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, DC. The Surratt boarding house still stands today at 604 H Street NW, Washington DC. It is currently in use as a Chinese restaurant and karaoke bar. Want to Learn More?

|

Last updated: August 14, 2025