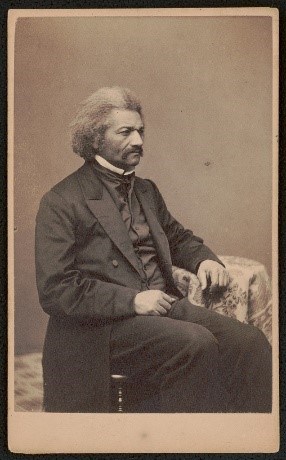

Library of Congress Once Black men were permitted in the military, Douglass served as a recruiter – most notably of the 54th & 55th Massachusetts Infantry. Two of his sons – Lewis & Charles – were among the recruits. Unfair treatment of Black soldiers persuaded Mr. Douglass to halt his efforts. “When I plead for recruits, I want to do it with my heart without qualification. I cannot do that now.” White soldiers were paid more. Promotions for Black soldiers were non-existent. Black men did not receive POW protections most white men benefitted from. “I must expose wrongs and plead their cause.” Hoping to fix these wrongs, Mr. Douglass traveled to Washington hoping to meet with President Lincoln.

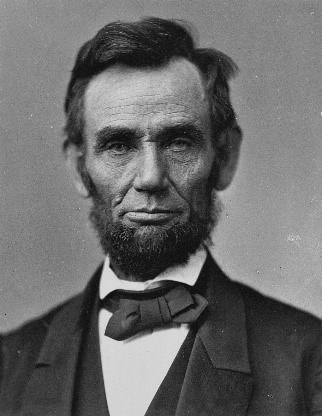

Library of Congress The First MeetingOn August 10, 1863 Frederick Douglass was in the Capital City. While in town, he visited many prominent officials. As he entered the White House, the 54th Massachusetts – soldiers he helped recruit had been cut to pieces at Fort Wagner in recent weeks. His oldest boy Lewis was lingering in a hospital from a devastating wound in that battle. His youngest boy Charles was fighting disease and illness. When the father of these wounded warriors arrived, he was immediately taken to see the President. “I was an ex-slave, identified with a despised race, and yet I was to meet the most exalted person in this great republic.” The Second MeetingOne year later, President Lincoln invited Frederick Douglass back to the White House. On August 19, 1864 Douglass and Lincoln were together again. The President was facing re-election soon and told Douglass he did not expect to win. If he lost, there would be a new President. With this in mind, Lincoln wanted Douglass to help with a special mission. Secretly, a revolution was afoot. Since the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln hoped for a mass exodus of enslaved individuals out of the states in rebellion. This had not happened on the scale he hoped. Now, Lincoln asked Douglass to lead a network of folks into the rebellious states to help every last soul possible escape enslavement. In language that must have reminded Douglass of his conversations years before with John Brown, the President of the United States was tasking him to help save thousands of lives, if not more. Douglass was asked to help destroy what remained of slavery. As a biographer observed, “Over night, Frederick Douglass went from frustrated outsider and fierce critic to special presidential advisor and organizer of a radical military mission.” After their meeting, Lincoln won re-election and this mission was unnecessary, but “for those hours at least the former slave from the Tuckahoe and the Indiana dirt farmer’s son were making a revolution together.” Though it never happened, it was now clear to Frederick Douglass that President Lincoln realized what was at heart of this war: the millions enslaved.

Library of Congress The Third MeetingAbraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass had one final meeting in March 1865. Douglass attended the inauguration, positioned very close to the President. At the end of the day, Douglass went to an inaugural event at the White House. After a few issues with police, Douglass got into the East Room where the President was. “Recognizing me, even before I reached him, he exclaimed so that all around him could hear, ‘Here comes my friend Douglass.’ Taking me by the hand, he said, ‘I am glad to see you. I saw you in the crowd to-day listening to my inaugural address; how did you like it?’ I said, ‘Mr. Lincoln, I must not detain you with my poor opinion, when there are thousands waiting to shake hands with you.’ ‘No, no,’ he said, ‘you must stop a little, Douglass; there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours. I want to know what you think of it?’ I replied, ‘Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort.’” A little over a month later, President Lincoln was murdered. Douglass lamented, “A simple leaden bullet and a few grains of powder are sufficient in the shortest limit of time to blast and ruin all that is precious in human existence.”

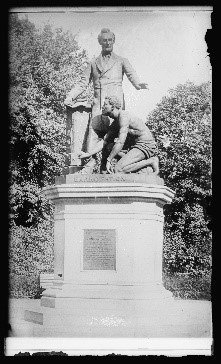

Library of Congress Lincoln’s MemoryFrederick Douglass outlived Lincoln by three decades. Across those years, he had many opportunities to talk and write about the slain President. Perhaps nowhere are Douglass’s memories of Lincoln more poignant than in a dedication speech for the Emancipation Memorial in Lincoln Park in Washington, DC in 1876. Highlighting the complex legacy of Lincoln, Douglass noted that “in his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man…You are the children of Abraham Lincoln. We are at best only his step-children.” Douglass recognized the question facing generations looking back upon Lincoln. To some, he was “tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent.” To others, he was “swift, zealous, radical, and determined.” To Douglass, Lincoln – whose portrait hung in his Study – was both…at different times. Depending on who you were and what you believed most important, you saw Lincoln in conflicting ways. Abraham Lincoln was a complex man, flawed, and full of contradictions. And so, too, was Frederick Douglass. |

Last updated: July 24, 2021