|

A big part of understanding caves is learning about the rock that makes up the cave. Learn the different types of rock found at Mammoth Cave and why they are the perfect combination to hold the longest cave system in the world.

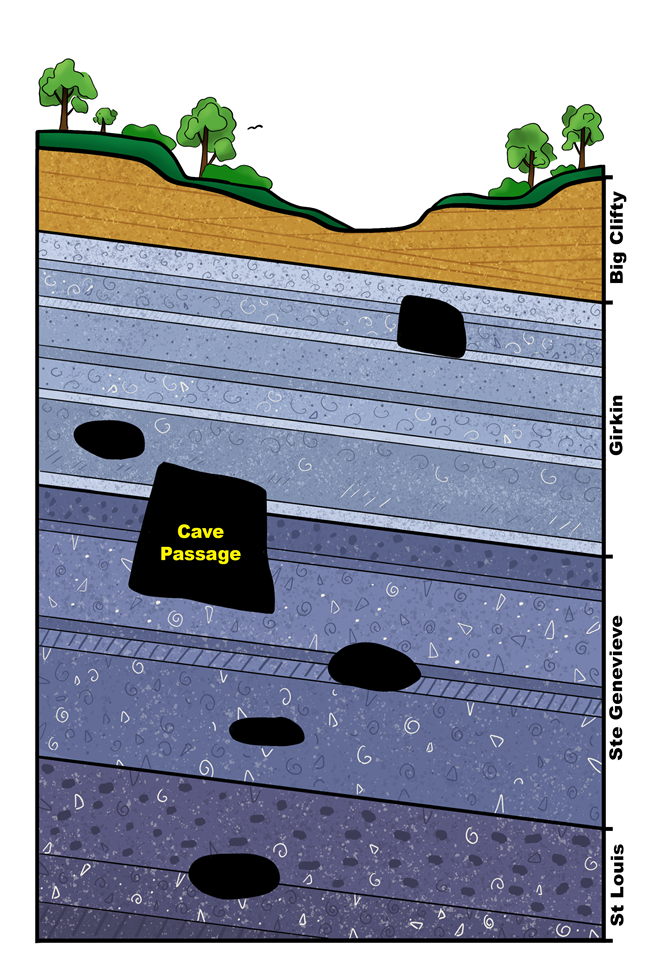

NPS Photo LimestoneThe most common rock in Mammoth Cave is limestone. Limestone is a sedimentary rock that allows cave passages to easily form because of its chemical makeup and ability to be dissolved by acidic groundwater. Mammoth Cave’s limestone formed about 330 million years ago at a time when a warm, shallow ocean covered much of the southern United States, including parts of Kentucky. Limestone forms when calcium carbonate (CaCO3) minerals in water cement together fossil fragments and other sediments gathered on the ocean floor. Over millions of years, this process creates limestone bedrock. Geologists classify Mammoth Cave’s limestone into three distinct formations (from youngest to oldest): Girkin, St. Genevieve, and St. Louis.

NPS Photo/ Kelli Tolleson ShaleShale forms when wet swampy clays and muds are compressed over the course of millions of years. The sediments that make up shale are tightly packed, this arrangement means that shale, unlike limestone, is not a porous rock. One of the shales at Mammoth Cave formed about 320 million years ago as the shallow sea receded and returned, depositing layers of shale above the limestone beds the cave is formed in. This shale is a caprock that serves as a sort of “roof” that protects the limestone layers and cave system below from leaks. This is one of the reasons that much of Mammoth Cave is dry.

NPS Photo SandstoneSandstone forms when tiny particles of sand, minerals, weathered rocks, and organic materials are compressed together tightly. Unlike limestone, sandstone is formed from rocks and minerals from the continental crust, rather than from minerals in the water of the ocean. One of the sandstones at Mammoth Cave, named the Big Clifty Sandstone, formed about 320 million years ago, when sand was deposited over top of Mammoth Cave’s shale and limestone beds by a large river delta. This sandstone is usually the top layer of the park’s many ridges, like Flint Ridge, Mammoth Cave Ridge, and Joppa Ridge because it is resistant to erosion. Other Rocks Found in Mammoth CaveWhile limestone makes up the majority of Mammoth Cave and shale and sandstone serve as its protective layer, other rocks contribute to the cave’s beauty and geology.

NPS Graphic/ Kait Evensen StratigraphyIn the book A Geological Guide to Mammoth Cave National Park, the renowned cave geologist, Art Palmer, invites his readers to “[I]magine making a vertical slice through the rocks of central Kentucky, so that you can view them from the side.”

How Mammoth Cave Formed

Towering passageways, mountainous heaps of fallen rock, and a maze-like sprawl.

Stalactites, Stalagmites, and Formations

Strange and one-of-a-kind formations.

Karst Topography

Sinkholes, sinking streams, caves and more!

Fossils

Life before the cave. |

Last updated: January 29, 2025