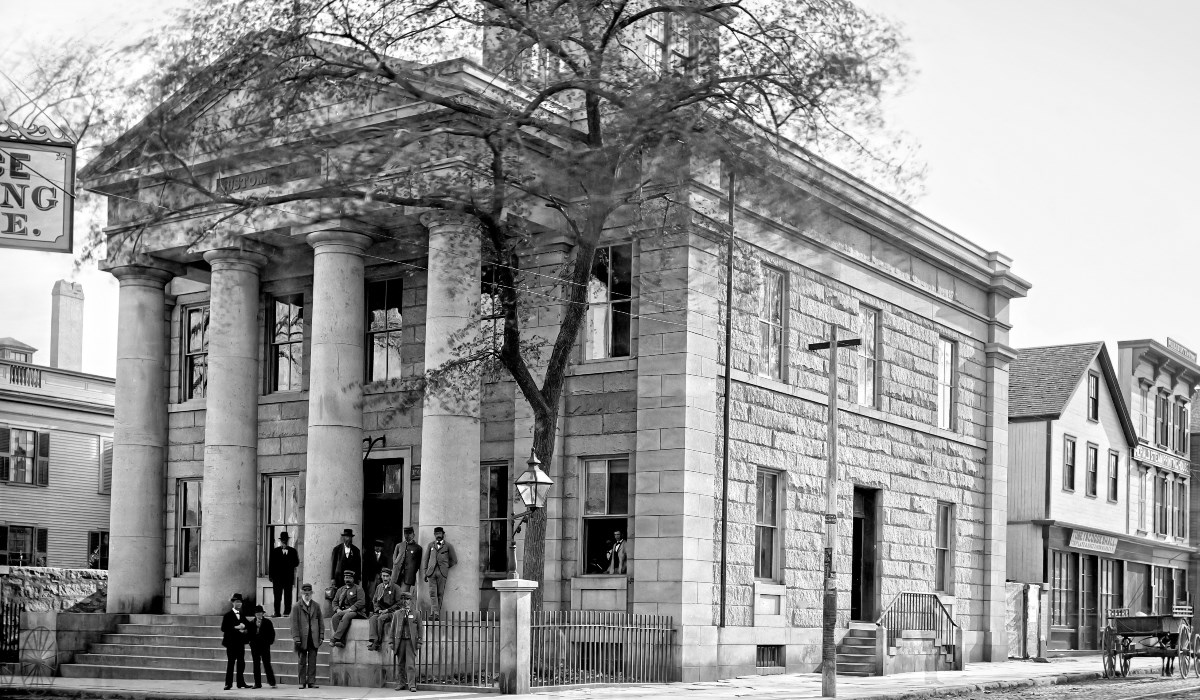

Completed in 1836, the U.S. Custom House in New Bedford is the oldest continuously operating custom house in the nation. It is also the largest of the four granite Greek Revival custom houses in New England designed by Robert Mills between 1834 and 1836. Robert Mills is the first internationally recognized architect that was both born and trained in America. He is most known for his designs in Washington D.C., including the Washington Monument, the Patent Office, the U.S. Treasury, and the General Post Office. The New Bedford Custom House was authorized by Congress on July 3, 1832. The site for the building was purchased on April 22, 1833 for $4,900. The cost of the finished building was approximately $25,500. Historically, whaling masters registered their ships and cargo at the two-storied, columned New Bedford Custom House. It also housed the city's first postal service. Although it is no longer a post office, today's commercial fishing and cargo ships continue to log duties and tariffs here, as it still serves as the New Bedford office of the U.S. Customs Service. The building also offices the National Marine Fisheries Service. The custom house's 37 N. Second Street location is within the boundaries of New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park and the New Bedford Historic District. This federal building is not open to the public.

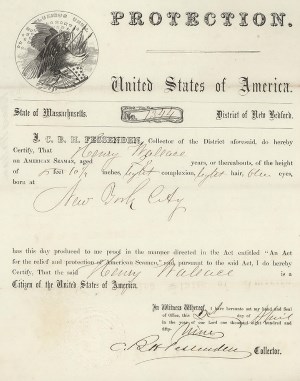

In the days of whaling, the U.S. Custom House issued Protection Certificates to American seamen as proof of citizenship. These printed documents protected Americans from impressment — or forced recruitment — by the British Royal Navy. The papers typically documented the seaman's name, birthplace, approximate age, physical features, and other distinctive information such as the location of scars or tattoos. While protection papers differ based on the local port they were drafted at, they typically included “United States of America” printed prominently across the top, engravings of the American eagle, and a serial number was for record keeping purposes. With the Act for the Protection and Relief of American Seamen (passed May, 28, 1796), an individual desiring protection was required to bring authenticated proof of citizenship to the customs collector; for a 25-cent service fee, he would then be issued a certificate. Prior to this act, a mariner could obtain a similar document from a public notary. Most seamen were so transient that they were unable to produce proof of citizenship. To accomodate, the standard changed to allow seamen to bring a notarized affidavit instead, in which the seamen and a witness swore to his citizenship. Because it was easy to abuse this system, the Royal Navy did not always honor the protection certificates as valid. For runaway slaves, working as a whaleman in the middle of the ocean offered them protection from slave catchers. But obtaining protection papers also certified their rights as sailors and free men. It wasn't foolproof; free blacks were sometimes captured and sold into slavery. Frederick Douglass had borrowed a friend's protection certificate when escaping north. Collectors were required to keep a record book of the names of individuals receiving protections and send quarterly lists to the state department. Protection Certificates were used as identification until 1940, when the Seamen’s Continuous Discharge Book replaced them. |

Last updated: August 2, 2018