MENU

Wright Brothers

| Mission

66 Visitor Centers

Chapter 2 |

|

Designing the Visitor

Center

During his speech at the 1957 First Flight Anniversary ceremony, Conrad Wirth described "major developments" scheduled for Wright Brothers Memorial over the next two years. The Park Service planned to proceed immediately with construction of a new entrance road and parking lot for the visitor center. Actual construction of the visitor center would begin during the next fiscal year. The new building would "accommodate visitors in large numbers . . . provide for their physical comforts . . . and present the story of the Wright Brothers at Kill Devil Hill in the most effective way graphic arts and modern museum practice can do it." [30] Wirth's remarks seem innocent enough, but the new building transformed the visitor experience at Wright Brothers. As historian Andrew Hewes pointed out in 1967, the focus of site interpretation shifted from the memorial shaft to the visitor center. The interior of the shaft and a stairway to the top of the monument had been open to visitors since its creation, but in 1960 access was closed. During an August 1958 committee meeting, members agreed that "special consideration be given to directing people to the first flight area rather than to the memorial feature." [31]Excitement over what shape the visitor center might take increased after the groundbreaking at the anniversary ceremony. According to Superintendent Dough's monthly report, "Mr. Benson of EODC and Messrs. Mitchell, Cunningham and Giurgola" visited the site on March 15 "in order to work up final drawing plans for the visitor center." These were actually preliminary design studies, the first of over one hundred sketches and drawings created for the visitor center. The next month, "Messrs. Tom Moran, Harvey H. Cornell (landscape architect), Donald F. Benson and others" gathered to discuss the location of the visitor center and parking area. The Superintendent included an uncharacteristically lengthy comment on the results of these meetings:

The final plan reflects contributions from the Washington, Region One, EODC and Memorial offices as well as contributions of members of the architectural firm preparing the plans. It always impresses us to witness the Service planning a development as a team; wherein, after an exchange of ideas, the end product is better than any one individual or office could plan. [32]

This collaborative effort took shape in the Park Service's development drawings of Route 158 (still under construction), the entrance road to the monument, the parking lot, visitor center footprint, and paths to the quarters and hanger. [33] The location of these features and the connections between them were approved by John Cabot, Regional Director Elbert Cox, Thomas Vint, and Conrad Wirth between April and June 1958. As the Mission 66 report for the park emphasized, the visitor center was to be "within the Memorial near the camp buildings" and a trail would lead from the facility to the first flight area. [34] Mitchell corroborated that the siting of the building was entirely a Park Service decision. The site was "exactly what they dictated. The location was specified as being close to the flight line." In a recent letter, Giurgola agreed that the site "was carefully planned while working closely with the NPS." [35] The Park Service wanted the public to stand under the dome and be able to see the monument and first flight markers from inside the building. [36]

Mitchell/Giurgola's early sketches on yellow trace, produced in March and April 1958, included several very different ideas for the overall plan of the building and its exhibition space. In one case, the architects envisioned an office wing separated from the rest of the building by a landscaped courtyard; the gallery was two stories. They also considered placing the central lobby and information area between an office wing and exhibit gallery. A version of the compact organization that would become their final choice was considered in March but not accepted until later in the design process. The architects' proposals for the double-height gallery and fenestration demonstrated their interest in creating dramatic effects of light and shadow, not to mention maximizing the opportunity to frame specific exterior views. Fenestration possibilities ranged from triangular mullion designs to vertical and horizontal patterns on the upper half of the exhibit space. These window arrangements were coordinated with first-floor windows, usually of a contrasting design. One perspective shows this gallery as a glass-walled cylinder; another slices a parachute-shaped roof open in the center and inserts a half-moon of glass. In some of the sketches the architects used brilliant colors—bright white, yellow and turquoise—to emphasize the contrast between translucent and solid sections of the window walls. Subtle changes in the patterning of window facades and ceilings altered the effect of mass, causing the gallery to "float." Throughout their artistic experiments, Mitchell and Giurgola were considering the location of the building in relation to the hilltop monument and the flight area. Preliminary site sketches include arrows indicating vistas from the building to these points of interest. The firm's early design efforts demonstrate a wide range of possibilities, but none that compare with the final plan in terms of clarity of program, circulation, and function. [37]

While the architects worked with possible design schemes, the park turned its attention to construction of the parking facilities accompanying the new building. In June the contract for the new entrance road and parking area was awarded to Dickerson, Inc., of Monroe, North Carolina, for the low bid of $73,930. The 0.56 mile road and parking area was to be completed within two hundred and fifty days. A group of EODC architects and landscape architects—Zimmer, Moran, Roberts, and McGinnis—visited in August "to discuss plans for the Visitor Center and Parking Area." [38] As Dough remarked, "the completion of the road project will pave the way for the building contractor." [39] The planning for the visitor center project also provided the incentive to finalize a land acquisition deal for which state funds had already been allotted. Congress authorized the Memorial's boundary expansion in June 1959, adding an additional one hundred and eleven acres to the park. [40] This extension provided the additional land to the east and north of the building necessary to include the fourth landing marker and parking lot.

Figure 19. Wright Brothers Visitor Center. This view of the memorial and flight markers from the ceremonial terrace was a preliminary drawing completed in August 1958.

(Courtesy of National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.)The preliminary plans submitted by Mitchell/Giurgola at the end of the summer were visually pleasing as well as instantly readable. The initial sketch in the series only depicts the building's ceremonial terrace, the roof overhang, and the edge of the lobby framing a panoramic view of the monument, barracks, and take off and flight markers. The final plan organized the elements of the program within a square, avoiding the potential monotony of such geometry by alternating interior spaces with open exterior terraces. The architects' early sketches suggest that their artistic exuberance might have been a little shocking to their Park Service clients. Perhaps in an effort to temper the more unusual aspects of the design, Mitchell/Giurgola produced several more subtle sketches. In elevation, the shell roof appears to diminish; from some angles it appears to dominate the structure, but as the building is approached, the dome gradually levels out and almost disappears. Among the preliminaries is a view of the building and the distant Wright Brothers monument against the night sky. Two-thirds of the paper is black and the building barely distinguishable among the trees and gentle rise of the horizon. Attention is focused on the road leading into the park, an exiting car, and a car passing by on the main highway. [41]

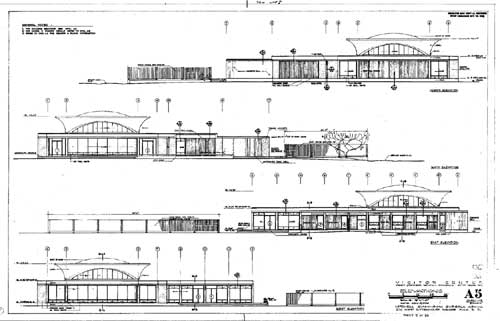

Figure 20. Wright Brothers Visitor Center, presentation drawing, 1959.

(Courtesy of National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.)The Park Service invited Stick and his committee to a meeting for review of the preliminary plans of the building and exhibits on July 28, 1958. In August members of the committee awaited copies of the revised building plans. A misunderstanding prevented Mitchell/Giurgola from beginning the working drawings, and when Cabot asked about their progress in late September, they were stunned. Despite this slow start, the architects rushed to complete the required drawings by the December 7 deadline. The working drawings essentially refined the designs presented earlier, but the cover sheet depicts an unusual perspective of the floor plan. The axonometric aerial view emphasizes the extent of window space, shown as thin, solid lines, in contrast to the three-dimensional walls. A plan and elevation appeared in a February 1959 "news report" in the popular journal Progressive Architecture. The short description, "Two Visitors' Centers Exemplify New Park Architecture," noted that "the design of visitors' facilities provided for national tourist attractions seems to be decidedly on the upgrade, at least as far as the work for the National Park Service is concerned."

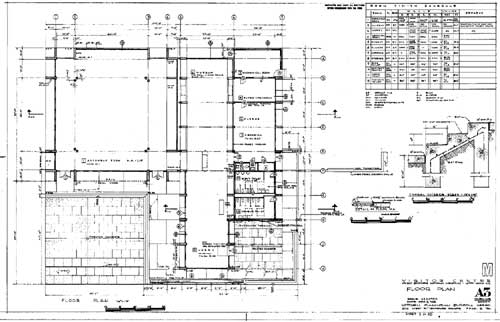

Figures 21 and 22. Wright Brothers Visitor Center. The plans, sections and elevations of the building were completed in December 1958.

(click on images for larger size)Perhaps not coincidentally, the other visitor center pictured was the work of Bellante & Clauss at Mammoth Cave National Park. [42] Later that year, the architects submitted a presentation drawing, complete with a small boy flying a toy plane in front of the ceremonial terrace, and a twelve-inch sectional model of half of the exhibit hall (see figure 20 on page 77). The model effectively demonstrated the building's innovative air circulation system with a cut-away view of the duct in the assembly room. In section, the concrete dome appeared lighter and more "wing-like" than depicted by drawings.

As December 7 approached, the committee began planning for its annual celebration, combined this year with the observance of the 50th anniversary of the United States Air Force. The committee hoped that a ground breaking or cornerstone laying ceremony might be included in the festivities. A month earlier, Lee reported that the final drawing for the visitor center was not complete and, therefore, the accurate laying of a cornerstone impossible. [43] The Park Service chose to initiate the Mission 66 program at Wright Brothers with a speech by Conrad Wirth outlining improvements scheduled for the Memorial over the next two years. Wirth had the honor of digging the first shovel of earth at the site of the future visitor center with a silver spade. [44]

In a one-sheet resume promoting Mitchell/Giurgola, written a few years after the visitor center dedication, the architects described the Wright Brothers commission as "among our major projects" and went on to discuss its design in some detail. The "dome-like structure over the assembly area," though technically "a transitional thin shell concrete roof with opposed thin shell overhangs connecting the perimeter of the structure to form a complete monolithic unit," also had a symbolic role. The roof structure design "admirably serves to allow light into the display area of the aircraft to give this area a significant character as well as forming a strong focal point on the exterior of the structure which stands above the low-lying landscape, in concert with the higher rising dunes and pylon." Evidently, the north concrete wall of the entrance terrace had been the subject of considerable public speculation. Here, and in their resume, the architects explained that the patterned wall was intended "to be an expression of the plastic quality of concrete by means of well-defined profiles, recessions and protrusions, simply placed to form an integral pattern over the wall surface." Not only did the wall feature rigid and curved shapes, but also contrast in depth and surface, as sections of the wall were bush hammered. In effect, the concrete patterned wall was public art. [45]

The attention lavished on aesthetics and symbolic purpose, as described by Mitchell/Giurgola, did not detract from the visitor center's practical function. Visitors appreciated the straightforward approach to the building from the parking lot and the exterior restrooms adjacent the entrance terrace. They may not have noticed the unusual shape of the drinking fountains, with their molded concrete basins, or paid much attention to the undulations and protrusions of the sculpted wall. But even at the most basic level, these design elements suggested the free-flowing form of both sand dunes and objects that fly. The entrance terrace was also part of the 128-foot-square concrete platform elevating the entire building a few feet above the ground. Steps extended to either edge of the terrace, and visitors crossed the open area to reach the double glass doors leading into the lobby. At this point, visitors were also invited to walk around the building to the ceremonial terrace. The entrance facade was full-height steel-framed windows divided by concrete piers, a pattern of bays encircling the building. Similar windows formed the far wall of the lobby, which could be seen by looking through the building from the terrace.

Upon entering the visitor center, attention was immediately directed towards the ceremonial terrace outside and the first flight monuments beyond. The Park Service information desk was actually located behind the visitor at this point. Since the lobby space flowed into the exhibit room, visitors gravitated to this area after taking in the view. The walls of the exhibit area were entirely covered with vertical tongue-and-groove cypress boards and wood paneling. This interior treatment, combined with the lack of windows, resulted in an inward-looking museum space conducive to study. [46] Park offices were located to the left of the exhibit area. Once visitors had followed the exhibits in a rectangular pattern around the museum, they found themselves at the entrance to the assembly room. In contrast to the muted tones and contemplative mood of the museum, the assembly room was a double-height space full of light from the three clerestory windows in its shell roof and the floor-to-ceiling windows on three sides. The shell roof, the 40-foot-square shape of the space, and the square mirrored above in the corrugated concrete overhang also emphasize the importance of the replica 1903 flyer in the center of the room. This assembly area was intended to substitute for an audio-visual or auditorium space, and in their presentations, Park Service interpreters would not only use the plane as a prop, but point out the flight markers, hangar and living quarters, and distant hilltop monument. Double doors at either end of the south facade led out to the ceremonial terrace. When groups gathered here for the annual celebration and other events, the Memorial's significant features stood in the background.

Although the interior contrasts in ceiling height and the amount of light emitted into the spaces belies the fact, the visitor center's walls are divided into equally spaced bays; whereas the assembly room is all glass, however, the office and exhibit spaces alternate cypress wood panels with sections of treated concrete. The faces of the piers are bush hammered. These surface contrasts force the visitor to pay attention to the composition of materials: the durable cypress wood, traditionally used in boat building, and the color and texture of the aggregate, which includes sparkling chunks of quartz and other arresting stones. In theory and practice, the Wright Brothers Visitor Center was a balance between aesthetics and function.

Figure 23. Wright Brothers Visitor Center, view of "patterned wall" from entrance, 1999.

(Photo by author.)The best example of Mitchell/Giurgola's concern with aesthetically pleasing structure is also the least noticeable. The mechanical systems for heating and cooling the building were "inconspicuously incorporated" into the building. Progressive Architecture was particularly interested in the "water-to-water heat pump" that both took advantage of the oceanfront location and eliminated the need to compromise the building's "vast horizontality with a vertical stack." [47] Fan-coil units and ducts were hidden above a suspended ceiling in the lobby and museum, but in the assembly room, they became part of the interior decoration. The corrugated concrete overhang houses ducts that pull in fresh air from outside, and the "soffit" below is a "continuous slot" for return air. Frederick W. Schwarz of Morton, Pennsylvania, was the consulting engineer for the heating and air conditioning system.

|

History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/allaback/vc2b.htm

![]()