|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 12: STABILIZATION: THE HIGH COST OF WATER (continued)

1934-1936

As outlined in Chapter 7, between 1934 and 1936 some ruins repair was included in general clean-up and refurbishment, trail building, and flood-control activities under government relief funds. A major project of that time was the rebuilding of much of the outer north and west walls of the pueblo. This was made necessary when, during removal of debris from the exteriors of those walls to better delineate the ruin, it was discovered that they were in very poor state of repair. Therefore, Public Works Administration crews, with Morris acting as supervisor, gradually razed and rebuilt large portions of this part of the West Ruin. Morris cautioned the crews to be careful not to add to or subtract from what was actually existent when first discovered. Workmen reset stones in their original position using cement mortar and replaced some rotten wooden elements. In the North Wing, they removed untinted cement cappings and replaced them. To make the mortar less noticeable, they carefully pushed it well back of the rock facing.

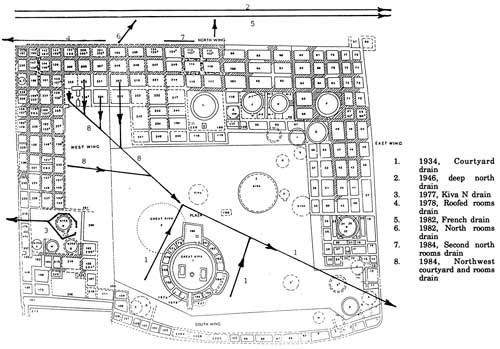

Concurrent with the wall rebuilding, other laborers made an attempt to prevent ground water from getting into roofed Kiva E, the Great Kiva, and additional subterranean features by laying a subsurface drainage system in the courtyard of the ruin. [31] The plaza drainage system consisted of a 10-inch tile drain placed next to Kiva E at a depth of approximately 17 feet (see Figure 12.4). It had underground branch lines radiating outward, including several drop inlets to interrupt the normal surface runoff within the courtyard. When the Great Kiva was restored, its considerable roof runoff was channeled into the primary line. Although it was reported to deliver approximately 200 to 250 gallons of water every 24 hours, the drain became progressively ineffectual and ceased to work altogether in early 1938. This was due to blockage of the main line by mud and vegetation, breakage of tiles, and the very slight gradient of the outflow. [32]

Figure 12.4. Schematic plan of major drains, West Ruin.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Hamilton designed and installed an experimental type of reinforced concrete roof over intact ceilings of two rooms. Modeled after a comparable experimental roof already in place in Pueblo Bonito, they were meant as catch basins where water would evaporate in place. [33] After Hamilton tried to patch several of the concrete covers fabricated by Morris, he concluded, "It is certain that the old concrete covers will have to be removed and entirely new covers built."

Engineers drew designs for additional projects. Among these were recapping the triangular spaces around kivas within the room block, providing air vents through the kiva walls, and setting the cap onto walls rather than the dirt fill. [34] They prepared a plan for reroofing Kiva E, which still had its old Morris wood, tar paper, and cement cover, with a new reinforced cement slab raised a foot above four girders.

Because the Great Kiva reconstruction absorbed the allocated funds, these various contemplated repairs remained in limbo but gradually were incorporated into an evolving 10-year program for protection of Southwestern ruins. [35] Previously in the early 1930s, Pinkley asked Faris to develop a six-year repair plan for the monument, but it was lost in the flood of developments made possible by federal relief programs. [36]

Because of his experiences during the Public Works Administration programs at Mesa Verde and Aztec Ruins, Morris favored a permanent plan for ruin survey within the National Park Service holdings synchronized with an annual schedule of repairs. His qualifications for an individual to head such an endeavor included a range of skills such as had not been generally cultivated in the new field of ruin stabilization, other than in Morris himself. As he wrote the director of the National Park Service, a person to lead this important task should have "practical commonsense, intimate familiarity with and understanding of the material used by the ancient builders, wide and penetrating observation of original methods of construction, a working knowledge of masonry technique, an eye to aesthetic effect, and intense interest in the work at hand." [37] These qualifications were in addition to a great deal of actual experience.

By the summer of 1935, something had to be done about the wetness of Kiva E. The idea of the moment for correcting this situation was a fan to circulate air. Investigation by Faris revealed that he could procure a 12-inch exhaust fan for about $32 to $100. It could be installed by the kiva's ventilator shaft or framed into the roof. His financial account had neither the necessary balance for such a purchase nor funds to cover the electric bill that would result from continual use of the appliance. An alternative was a sump pump operated by a float switch, but this was more costly. The third idea was to install tile drains within the kiva connecting to the main courtyard drain. That would have meant removing and rebuilding the hearth and ventilator opening. Besides, the primary drain outside the kiva already was showing signs of becoming useless. [38] Faris decided to try a fan specially built with motor and blades fashioned to his particular needs. How he financed it is unknown. For a time, the fan seemed to help dry out the chamber. [39]

Meantime, National Park Service engineers went to work on the basic problem of seepage. They drafted Plan AZT-4958. It called for excavating into the floor of Kiva E to reach the primary court drainage line, laying soil pipe and fittings in a gravel and sand bed, and backfilling the trench. This could be done at a cost of $375. [40] Even though Chief Engineer Frank A. Kittredge had included Aztec Ruins National Monument in his general request of the previous summer for $150,000 for protection of Southwestern ruins, there was no money to carry out this particular job. [41]

Troubles mounted during the winter of 1936, as, with a single exception, all the protective roofs over Anasazi ceilings failed. Faris did what he did with regularity: he sent off a request for a supplemental appropriation for ruin repairs. He got his usual reply. Hugh M. Miller, then acting superintendent of Southwest Monuments in Pinkley's absence, curtly said that since the monument had received a large sum for that purpose as recently as two years previously, the request would be met with a cool reception. Miller continued, "It is going to be a little awkward to explain to the Secretary that we had the money but spent most of it for restoration of the Great Kiva and neglected urgent work on the main ruin." [42]

Faris persisted with a following letter to Pinkley, explaining that eight or 10 roofs simply had to be repaired at once and the remaining 15 shortly thereafter. He hoped perhaps another contingent of Civilian Conservation Corps youths could be put to work on damaged walls, if only somehow $500 could be found. [43] In hopes of favorable response, he obtained a print of Engineer Hamilton's plan (AZ 4950) for placement of roofs over original ceilings. [44] Since Faris's request of March was met with silence, in June, he forwarded to Superintendent Pinkley yet another one for repair funds. This time the amount was set at a whopping $7,400 to pay for 20 catchment-type protective roofs, reroofing Kiva E with the reinforced cement covering designed in 1934, and a protective cement roof over Room 117 with incised murals. [45]

On August 30, a two-inch downpour engulfed the monument within an hour. One can feel the tone of despair as Faris lamented to Pinkley, "There is about five inches of water in our roofed kiva [Kiva E], several walls fell in and the bench around our show kiva [Great Kiva] where the logs were exposed which contained the offerings is falling down at an alarming rate. The big drain trench settled in several places leaving large holes, low places are filled with muck and stagnant water. The whole place carried a terrible odor from the mess and weeds have popped up six inches in the past two days." [46] To top it off, the fan in Kiva E was drowned and destroyed. Five unidentified Anasazi ceilings were repaired shortly before the storm; the remainder held. [47]

Engineers from the San Francisco office determined that so much water rushed down or over the roof spouts of the Great Kiva, some of which were plugged, that the court drain was unable to carry it out of the area rapidly enough to prevent it from backing up into Kiva E. [48]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/adhi12c.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006