|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 6: THE DECADE OF DISSENTION, 1923-1933 (continued)

THE ARCHEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS AND THEIR EXHIBITION IN

THE FIRST TWO MUSEUMS

(continued)

Reflective of the range of artifacts collected from the site, pottery was predominately represented in the loan collection by 139 vessels and a few sherd assortments of both decorated and corrugated styles. Several examples of trade pottery were included, as were two examples that Morris called "archaic." These probably were scavenged from earlier dwellings in the surrounding valley. Of special interest were 11 vessels from Kiva Q and 24 from Kiva R recovered by Morris in 1921 and considered by him to confirm the earlier Chaco occupation. Morris also loaned Boundey manos, metates, grooved axes, chipped knife blades, arrowheads, beads, pendants, quartz crystals, sandals, and one incomplete coiled basket. He likewise offered for exhibit the remains of two children from East Wing rooms, one a burial bundle and the other a skeleton.

Not satisfied with the American Museum loan, Boundey solicited additional contributions from valley residents having assorted "relics." He claimed that more than 500 such articles were turned over to him. [78] Three hundred forty-one specimens received during Boundey's time at Aztec Ruin can be accounted for. Current Aztec museum accession records indicate that a collection of 142 objects was loaned by Sherman Howe on August 25, 1927. In 1928, Mrs. Oren F. Randall, of Aztec, placed 36 specimens at the monument on a 10-year loan. [79] The largest contribution was that by Abrams's widow, Rosa, who loaned 163 specimens in 1928. [80]

Stimulated by Boundey, Mrs. Abrams sought to get returned the specimen collection promised to her late husband. Wissler recognized the legitimacy of her request and expressed regret that so many years had passed without the full analysis of the Anasazi material culture represented by the articles. [81] A search at the American Museum revealed that Morris actually had published on some of the specimens chosen in 1917 for Abrams. This increased the importance of their being held at the museum, as did the necessity of keeping intact some group lots, such as beads making up necklaces. Wissler suggested privately that Morris make suitable substitutions from other assortments of Aztec Ruin artifacts. He added a handwritten note on the margin of his letter to Morris that there was no reason for Mrs. Abrams to know of this action. Wissler had no thought of cheating her, but such a step could be misunderstood by those already antagonistic toward the museum. [82]

When Morris was in New York later that fall, he sorted through the storage cabinets and withdrew 43 catalogue entries for Mrs. Abrams. Thirteen were from the Abrams list of 1917, the remainder being substitutions. None of the artifacts illustrated in the report of 1917 was included. Five examples were from sites other than the West Ruin. Perhaps some of those had been on the Abrams farm but were eradicated. [83] The quality of these selections ranged from excellent to poor, as did those taken from the ruin itself. They included pottery of various decorative styles and forms, bone awls, bone tubes, bone scrapers, fiber pot rests, yucca sandals, a hair brush, fragments of cotton cloth, and one packet of 25 of an original cache of 200 arrowpoints. The number of these specimens seems small when considering that the initial division for Abrams was planned to be about 20 percent of the total. However, they were representative of the full variety of most typical goods and were to go to a site museum that already had 261 specimens and the prospects of hundreds more from those stored at the American Museum field headquarters.

This retrieved collection probably formed part of the much larger assortment of artifacts Mrs. Abrams turned over to Boundey. The bulk of that grouping must have been specimens gathered by her late husband over many years at Aztec Ruin and elsewhere in the Animas valley. More than half of them had no known provenience other than the general vicinity.

Without doubt, the amateur collectors took pride in having their own special possessions on public display. Although there was the danger that it encouraged further illicit digging, the inclusion of their specimens fostered the good will of local people. The specimens exemplified Anasazi mode of life, but their scientific value was diminished by lack of pertinent data about them. Many of the sites within the Animas valley from which they had been taken no longer existed; if they did, circumstances of artifact deposition were not known. Many of those sites in adjacent regions were not sufficiently studied to determine their cultural affiliation. Nowadays, official policy excludes artifacts not recovered on the monument. [84]

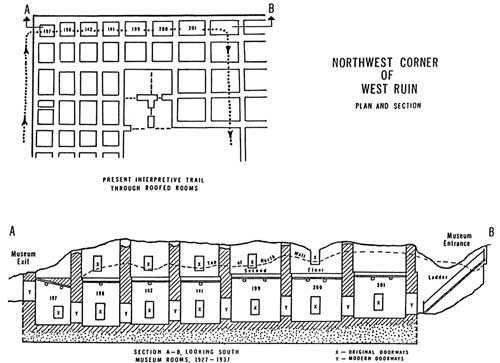

If there were questions about the objects shown in Boundey's museum, there were more about the facility itself. Rooms 197, 198, 141, 142, 199, 200, and 201 on the first floor of the northwest corner of the North Wing of the house block were those originally entered in 1882 by regional schoolboys and their teacher. Room 197 at the west corner was partially exposed by a fallen ceiling. After working down to its floor level, the intruders tunneled horizontally eastward from one room to another, breaking jagged holes in partitioning masonry walls. The Anasazi doorways opened to the south. Each cellular room with original ceiling intact along the northern outer wall was totally dark. There were no windows on the outside wall of the village compound, and small ventilation openings to that exposure were covered with drifted debris. Rooms on the southern flank also were covered. Entrance to the area was by means of a wooden ladder down a mounded area over Room 193. Boundey opened a line of communication from east to west through seven rooms by shaping the irregular settler breaches into doorways (see Figure 6.4). [85] Locked wooden doors were put at each end of this passage (see Figure 6.5). [86] Light from kerosene lanterns provided artificial illumination until the unroofed quarters along the southern side of the museum rooms were cleared in order that natural daylight could pour into the darkened recesses. [87] Electricity was extended to the monument in 1928. A planned wooden plank floor to cover the packed earth original never was laid. Winter visitation was expected to be uncomfortable, consequently brief, since the interior stone chambers retained numbing cold and dampness.

Figure 6.4. Northwest corner of West Ruin, plan and section.

(click on image for larger size)

Figure 6.5. West exit from roofed rooms of North Wing used

from 1927

through 1937 as the second museum at Aztec Ruin.

Today's standards condemn modern remodeling to create doorways where they had not been prehistorically and in so doing destroy the structure's integrity. In the 1920s, this was regarded as no more outrageous than Morris's adding roofs to some ancient dwellings. It was the removal of debris from the chambers to the south of the line of proposed museum rooms to provide light for the museum to which professionals objected. The cleared rooms later were numbered 239, 147, 144, 126, 205, and 206. Boundey began work in them in December 1927 and continued into the early spring of 1928. [88]

Later, Boundey stated that he carefully drew a plan of each room and indicated on it the exact locations where artifacts were unearthed. [89] No such records have been found. Moreover, Boundey's system for cataloging the 227 recovered specimens was not understood by later researchers. Approximately 135 photographs, which seem to be those of the museum displays but taken outdoors, are unidentified groups of objects on cloth-draped shelves. [90] Lacking close-up views of catalogue numbers on them, it would be a time consuming, maybe fruitless, effort to correlate photographs and objects. Some photographs may have been of ceramics restored in the 1930s. At any rate, it appears likely that Boundey was accused wrongfully of willful pothunting without regard to maintaining proper documentation. His crime was not to provide data in a form recognizable by those who came later. [91]

After reporting on several occasions the work to provide light for the make-do museum, Pinkley received a severely worded directive from Director Mather. Neil Judd, Southwestern archeologist on the staff of the U.S. National Museum and long-time friend of Morris, lodged a strong protest about reputed illegitimate digging at Aztec. Whether Morris had a hand in bringing the problem to public attention is unknown. Mather wrote that activity being done at Aztec Ruin by an untrained person lacking proper authorization would bring criticism of the National Park Service, was to be discontinued immediately, and that the custodian should be instructed to confine his efforts to administration and protection of the monument. Pinkley's unfounded protests that Boundey reclaimed artifacts missed by Morris were ignored. [92] Morris excavated only the second-story units now numbered Rooms 191, 195, and 196, none of those below. [93] The earliest Euro-American entrants on the ground level cleaned out whatever items were visible on the surface. Boundey undertook to finish the job and did recover some overlooked artifacts. [94] Morris had not touched the rooms to their south.

Officials at the Department of the Interior asked Jesse Nusbaum, advisor to the department, to look into what was going on at Aztec. Nusbaum's main complaint was that the excavation was being done without the permit which government authorities saw as a necessary means of curbing vandalism of culturally important resources. By implication, he recommended that work cease at Aztec.

Expectedly, Boundey became defensive. According to him, the Morris house was built to serve as a fireproof museum. Because of Morris's refusal to allow it to be used for that purpose, Boundey was forced into the action he took. He continued, "When I was a boy of twelve I owned 1,000 perfect arrow points and was known as "Arrowhead George." Have been digging for thirty years, have never sold an article for money and everything excavated is in some Public museum." [95]

To soften his own criticism, Nusbaum acknowledged that the editor of the Durango Democrat Herald reported in his newspaper that a recent tour of Aztec Ruin was the most educational of any he had taken in 25 years. [96] That statement probably reflected the feelings of many others. Boundey personally guided each visitor or group of visitors around the ruin, ending the tour by walking through the new museum. Whether his interpretations were correct or current remains questionable. He was not well grounded in Anasazi research. Furthermore, he could not singlehandedly deal with the acceleration of tourist traffic. Volunteers, including Sherman Howe, were called upon to take people through the ruins, while Boundey remained stationed in the museum. [97]

In the museum as it was then set up, the large specimens were placed where they might have been used by the ancient residents. Small objects, such as beads, awls, or arrowpoints, were exhibited in cotton-lined mounts. [98] Many visitors found the hushed, dark atmosphere of the rooms intriguing and likely came away with a heightened appreciation for the architectural skills of the Anasazi. Nonetheless, the open displays and dearth of labels or other descriptive materials meant that the custodian had to be at their elbows to function both as guard and instructor. The lack of protective covering for some kinds of artifactual materials invited possible theft or harm from uncontrolled atmospheric conditions. Their true worth was nullified by scarcity of relevant information.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/adhi6d-1.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006