![]()

MENU

Eruption and White Bird Canyon

Looking Glass's Camp and Cottonwood

Kamiah, Weippe, and Fort Fizzle

Cow Island and Cow Creek Canyon

Bear's Paw: Attack and Defense

Bear's Paw: Siege and Surrender

|

Nez Perce Summer, 1877

Chapter 9: Canyon Creek |

|

Chapter 9:

Canyon Creek (continued)

Within hours of the close of the encounter, Sturgis dashed off a note to be telegraphed to his superiors: "We have just had a hard fight with the Nez Perces lasting nearly all day. We killed and wounded a good many & captured several hundred head of stock. Reports not yet in and cannot give our loss but it is [a] considerable number killed & a good many wounded." [69] In fact, Sturgis's casualties in the Canyon Creek fighting totaled three enlisted men killed and an officer (Captain Thomas H. French) and eight men wounded, one of whom died later while being transported down the Yellowstone. Wilkinson's Company L, which was in the forefront in opening the action, sustained the heaviest losses, with two men killed and two wounded. The dead on the field were Private Edgar Archer (who actually survived until the fourteenth) and Private Nathan T. Brown, Company L, and Private Frank T. Goslin, of Company M. [70] (Brown served as acting sergeant major with Benteen's battalion.) That evening the soldiers buried Brown and Goslin in a trench. A witness said that the men "were literally shot to pieces, but no time was taken or effort expended in fixing or cleaning them up in any manner, but they were put into the trench with spurs, belts or other wearing apparel upon them." An officer conducted a service and a shot was fired over the graves. [71]

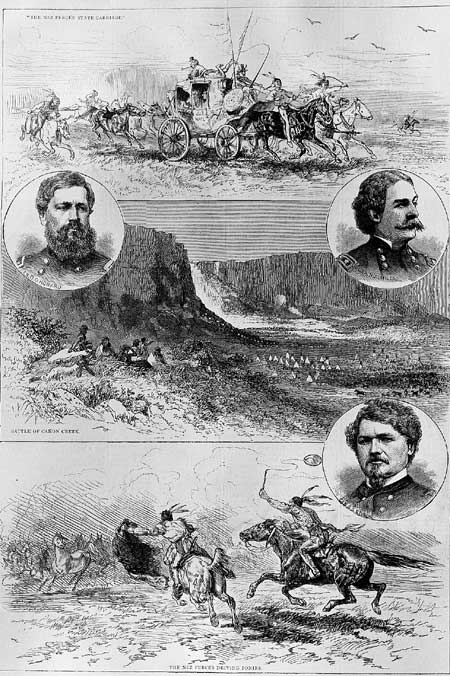

Contemporary media views of the Canyon Creek engagement as they appeared in Harper's Weekly, October 27, 1877 |

During the fighting at Canyon Creek, several episodes of a personal nature occurred regarding the soldiers. In one, a mixed-blood Bannock with Fisher went into the fray sporting "a bright scarlet Indian war-dress, topped out with an eagle-feathered war-bonnet." Although the scout, Charley Rainey, warned the soldiers not to shoot at him, apparently not all got the word. As Rainey and another scout, Baptiste Ouvrier, huddled among the sage cleaning their weapons after the fighting was well under way, a company of passing troopers spied them and, thinking them Nez Perces, leveled a volley their way, "cutting the feathers out of Charley's bonnet, shooting several holes through their clothing and tearing up the brush and dirt on all sides of them." [72] In another instance, Private James W. Butler of Company F was left behind in Merrill's initial advance because his mount was too fatigued to continue. Butler "followed rapidly on foot until he captured a pony, which he mounted bareback and galloped forward to the skirmish line, where he behaved gallantly during the fight." [73] The various scouts, both of Sturgis's and Howard's commands (evidently not constrained by the military discipline of the proceedings), ranged about—"bushwhacked around," said Redington—during the fighting and got involved in several small-scale skirmishes with the warriors. Redington was incredulous over one of these, in which a dozen or so scouts atop a knoll drew the warriors' attention:

A shower of hostile bullets went slap-bang right among and through them, zipping and pinging and spitting up little dabs of dust under their horses' feet, and before and behind them. Logically, every one of those scouts was scheduled to get shot. And yet neither man nor horse was hit. Why? Don't know! . . . Must have been thirteen guardian angels watching over each scout and diverting bullets by inches and half-inches. [74]

Later, while joining his colleagues in a flank attack on a Nez Perce position, Redington received a wound in the knee. "One of my fellow Boy Scouts took his mouthful of tobacco and slapped it onto the wound, making it stay put with a strip of his shirt. It smarted some, but caused hurry-up healing, and the few days' stiffness did not hinder horse-riding." [75] Redington further remembered the aftermath of the battle, when "we had to cut steaks from the horses and mules shot during the day. The meat was tough and stringy, for the poor animals had been ridden and packed for months, with only what grass they could pick up at night. But it was all the food we had." [76]

Trooper Jacob Horner recollected the lack of food and water during the day-long fight, and the suffering of the wounded soldiers afterwards, many of whom, over objections of medical personnel, drank stagnant alkali water collected from buffalo wallows to relieve their thirst. Horner also recalled Colonel Sturgis's tendency to spit tobacco "in every direction. The other officers moved away to avoid him." [77] On one occasion, Horner acted as a messenger for Sturgis:

Sturgis noticed that the troops, who were dismounted and firing on their bellies, were removed too far from their horses. He turned to me and ordered me to deliver a verbal message to Major Lewis Merrill to bring the horses closer. . . . I mounted and headed for the puffs of smoke. When I got into the center of action I suddenly had a strange feeling. I saw that I was the only mounted trooper in sight. What I had to do, had to be done quickly. The bullets were whining over the field. I spurred on to where I thought I might find the major. Suddenly I recognized him in the grass. The sun sparkled on his glasses. I knew it was him. I yelled the order and he acknowledged it with a grunt. I lost no time in wheeling my horse around and heading for headquarters. I escaped being hit. [78]

Horner recalled watching Sturgis when a man was brought to the headquarters area with a severely wounded heel. He saw the colonel wince at the sight of the injured youth, possibly reminded of the loss of his son with Custer the previous year. Horner watched as a buddy was brought in with a badly wounded arm requiring removal. "He asked me if I wanted to watch the amputation. I told him I would rather not." [79]

Most of the personal accounts agree that Benteen displayed great coolness and bravery in the Canyon Creek combat. One stated that after his surrender Joseph asked to see the officer who rode the buckskin horse at Canyon Creek and whom the warriors had tried repeatedly but unsuccessfully to shoot. He was described as having a "trout rod in his hand and a pipe in his mouth." It was Benteen. And although the accounts of Goldin and others are quick to condemn Sturgis's management of the engagement (some stated that he was afraid because of what had happened to the regiment at the Little Bighorn), most such judgments are without foundation. Even though Sturgis failed to finally deter the tribesmen at Canyon Creek, Private Horner remembered the colonel as genial, energetic, and cool in battle, and said that he was highly regarded by his soldiers. [80] From all indications, too, some Seventh Cavalry soldiers showed certain compassion for the Nez Perces in their struggle, perhaps because they had but recently joined in the campaign against them as opposed to Howard's men who had been in the field since June. The men of the Seventh had been reading of their plight in the newspapers for most of the summer, and Goldin not only confessed that "our sympathies were with the Indians," but noted admiringly that "the resourcefulness of those Indians was the cause of much talk among our men." He added that "we felt they had received more than the traditional Double Cross. We fought them, of course, but our hearts were not in it as in the case of the Siouz [sic], Cheyennes and Apaches." [81] Similarly, Trooper William C. Slaper of Company M recalled thinking that "the Nez Perces were a good people and very much abused by our pin-head Government officials." [82] Even those who had been on the trail now for months grudgingly admitted respect for their cause. Wrote Dr. FitzGerald of Howard's command, who had accompanied Sturgis to Canyon Creek: "Poor Nez Perces! . . . I am actually beginning to admire their bravery and endurance in the face of so many well-equipped enemies." [83]

Most of the Nez Perce accounts of the fighting at Canyon Creek, which they called Tepahlewam Wakuspah (Place Similar to the Split Rocks at Tolo Lake), [84] suggest that the immediate appearance of the troops was unforeseen, and that perhaps the warriors were so engrossed in their foraging activities down the Yellowstone on the morning of the thirteenth that they failed to keep scouts posted on the back trail. It is likely that had the Nez Perces not already been packed and on the move, Sturgis's attack would have had devastating results for them. Yellow Wolf indicated that only as the village packed up did he receive knowledge of the troops' advance. "I saw soldiers near, and across the valley from us. The traveling camp had nearly been surprised. Soldiers afoot—hundreds of them. I whipped my horse to his best, getting away from that danger." [85] As the families and horses began entering the mouth of the canyon, Yellow Wolf briefly joined the warrior, Teeto Hoonnod, who singlehandedly kept part of the troops at bay. This prominent man warned Yellow Wolf to get away, as he was drawing fire, and Yellow Wolf proceeded to withdraw and join the warriors guarding the families as they filed into the canyon. He saw what apparently was Benteen's movement to cut off the horses, interpreting it as a drive to capture the noncombatants. "They tried to get the women and children. But some of the warriors, not many, were too quick. Firing from a bluff, they killed and crippled a few of them, turning them back." [86] Referring to the climbing of Horse Cache Butte by some of Sturgis's troops late in the fighting, Yellow Wolf noted that these soldiers killed two horses and wounded a man named Silooyelam "in the left ankle." Two other Nee-Me-Poo casualties at Canyon Creek were Eeahlokoon, hit in the right leg, and Animal Entering a Hole, wounded in the left hip and thigh by a single bullet. Although Sturgis claimed that sixteen Indians were killed at Canyon Creek, the sole fatality acknowledged by the Nez Perces in the engagement was Tookleiks (Fish Trap), an elderly man who was trying to retrieve one of his horses when he was shot by the Crows. [87] The warrior Teeto Hoonnod stayed in position at the mouth of the canyon, performing a rearguard function until the tribal assemblage had gotten safely inside its walls. [88] After the battle, as the troops withdrew and went into camp near the mouth of the canyon, the Nez Perces bore left up the main branch of Canyon Creek. Yellow Wolf and others raised a barricade in the upper reaches to impede further pursuit. [89] "It was after dark when we reached camp. Staking our horses, we had supper, then lay down to sleep." [90]

Other than that of Yellow Wolf, few Nee-Me-Poo accounts described the combat at Canyon Creek, noting only that a confrontation occurred. Several, however, observed its significance for the people, primarily in that although the women and children and most of the livestock managed to escape, "we lost a large part of our herd of horses. This loss was a serious blow to us." The misfortune of losing the ponies at Canyon Creek (most of them appropriated by the Crows), with further such losses the next day, ultimately meant that the remaining animals had to compensate, and probably slowed the rate of march after that to an extent that it facilitated the army's effort to stop the Nez Perces. As Yellow Bull stated, "At Canyon Creek fight we lost many horses, and this crippled our transportation, making it hard work for us to get along." [91] Just as important, the loss of the animals—possibly coupled with the onset of a perceived deficiency in the amount of their available ammunition—seems to have contributed to growing dissension and outright quarreling among the people, [92] doubtless aggravated by the knowledge of the Crows' betrayal in direct opposition to what Looking Glass had predicted. [93] These factors, added to the real likelihood that the people were becoming physically exhausted from their three-months-long ordeal, constituted but part of the significance of Canyon Creek. Of greater magnitude, based on the perspective of later-unfolding events, was the critical loss of a full day's travel by the Nez Perces as the engagement with Sturgis occupied and thus delayed their progress. Although Sturgis failed to win a solid victory and stop the Indians and end the war, his action so thwarted them materially, physically, and psychologically that its significance, although perhaps not recognized at the time, became compelling in view of what happened to the tribesmen over the ensuing three weeks, and how, in turn, it affected their final defeat by the army.

The wounded of Sturgis's command suffered desperately from thirst on the days following the fighting. The colonel and his men departed on the trail on September 14, leaving them to the attention of appropriate medical personnel until the arrival of Howard's column and requisite transportation. First Lieutenant Charles A. Varnum, regimental quartermaster officer, then escorted the wounded forty miles down the north bank of the Yellowstone to Pompey's Pillar, where on the eighteenth a wide-bottomed mackinaw was engaged to carry them on to the Tongue River Cantonment. On the march from Canyon Creek, Varnum's procession encountered the famous Martha Jane ("Calamity Jane") Cannary, who reportedly had lived in a dugout near Horse Cache Butte on the battlefield and who had experienced a brief run-in with the Nez Perces near the Yellowstone. She now agreed to accompany the injured downriver as a nurse. Later on the eighteenth, at Terry's Landing, opposite the mouth of the Bighorn River, the boat halted while the body of Private James Lawler of Company G, who had died that day, was removed for burial. The remaining seven wounded reached Tongue River four days later where they were hospitalized. [94]

Virtually every officer who appeared on the field at Canyon Creek on September 13, 1877, received belated recognition for "gallant service in action" in the engagement when in 1890 Congress permitted the retroactive award of brevets by the War Department. By then, many of them were retired or deceased. Assistant Surgeons Jenkins A. FitzGerald (died in 1879) and Valery Havard were cited "for repeated exposure to the fire of the enemy in their humane efforts to extricate and take care of the wounded." Thirty enlisted participants likewise received citations for their efforts at Canyon Creek. [95]

Top

Top|

History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

Last Modified: Thurs, May 17 2001 10:08 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/greene1/chap9d.htm

![]()