|

MESA VERDE

Circular of General Information 1936 |

|

DATES FOR MESA VERDE RUINS ESTABLISHED BY THE TREE-RING CHRONOLOGY1

1The Secret of the Southwest Solved by Talkative Tree Rings, by A. E. Douglass: National Geographic Magazine, December 1929.

Dr. A. E. Douglass, director of Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, established the tree-ring chronology for dating Southwestern ruins. This chronology is based upon the facts that solar changes affect our weather and weather in turn the trees of the arid Southwest, as elsewhere, and that such affects are recorded in the variation of tree-ring growth during wet and dry years. Thus the tree-ring record of living trees has been extended into the past by arranging beams from historic pueblos in their proper sequence so that the inner diaries of one dovetailed the outer entries of its predecessor, and in turn overlapped the diary of the living trees. After completing the series from living trees and pueblos, of known dates, the record has been continued through the cross-sections of prehistoric beams of fir and pine that were chopped with the stone axes. The continuation of this chronology is only limited by the finding of earlier beams than those used in the established chronology.

The National Geographic Society tree-ring expedition took, in all, 49 beam sections from ruins within Mesa Verde National Park. During 1932 and 1933 further tree-ring research was carried on in this area and additional dates have been secured. Presuming that the year of cutting the timber was the year of actual use in construction, the following dates have been established for the major cliff dwellings:

| Mug House, A. D. 1066 | Long House, A. D. 1204-11 |

| Cliff Palace, A. D. 1073-1273 | Square Tower House, A. D. 1204-46 |

| Oak Tree House, A. D. 1112-84 | Spruce Tree House, A. D. 1230-74 |

| Spring House, A. D. 1115 | New Fire House, A. D. 1259 |

| Hemenway House, A. D. 1171 | Ruin No. 16, A. D. 1261 |

| Balcony House, A. D. 1190-1272 | Buzzard House, A. D. 1273 |

Since considerable tree-ring material from these ruins remains yet to be examined, the dates given above are not final. On the basis of present evidence, Cliff Palace, the largest and most complex cliff house within the park, shows an occupancy of 200 years.

It is an interesting fact that all of the dates fall just short of the beginning of the great drought, which the tree-ring chronology shows commenced in 1276 and extended to 1299, a period of 23 years.

DISCOVERIES OF RECENT YEARS

In 1923 Roy Henderson and A. B. Hardin discovered the largest and finest watchtower that had yet been found. The tower was circular, 25 feet in height and 11 feet in diameter. Loopholes at various levels commanded the approach from every exposed quarter.

During the winter of 1924 the north refuse space of Spruce Tree House was excavated. Two child burials were found, one partially mummified, the other skeletal only. With one was found a mug, a ladle, a digging stick, and two ring baskets that had held food. Several corrugated jars were found, together with miscellaneous material. A layer of turkey droppings a foot thick indicated the space had been used as a turkey pen.

During January and February of 1926, when snow was available as a water supply, excavations were carried on in Step House Cave, by Superintendent Jesse L. Nusbaum. In 1891 Nordenskiöld had found many fine burials in this cave and it had suffered greatly from pothunting. The cliff dweller refuse at the south end of the cave had not been thoroughly cleaned out, however, and it was under this layer of trash that the important discovery was made. Three of the Lake Basket Maker pit houses were found, giving the first evidence that these people had used the caves before the cliff dwellers. Very few artifacts were found because of the earlier pothunting. In 1926 also a low, deep cave opposite Fire Temple was excavated, and a small amount of Basket Maker material found. Most interesting were two tapered cylinders of crystallized salt that still bore the imprint of the molder's hands. While bracing a slipping boulder in Cliff Palace, Fred Jeeps found, in 1916, a sandal of the Early Basket Maker type that indicates a former occupancy of the cave by the first group of Agricultural Indians in this region.

In 1927 Bone Awl House was excavated. A series of unusually fine bone awls was found that suggested the name for the ruin. Much miscellaneous material was also found. Another small cliff dwelling nearby was cleaned out. One baby mummy and an adult burial were found, as well as some pottery and bone and stone tools. This ruin is reached by a spectacular series of 104 footholds that the cliff dwellers had cut in the almost perpendicular canyon wall.

During March of 1928 and the winter of 1929 restricted excavations were conducted in ruins 11 to 19, inclusive, on the west side of Wetherill Mesa. Several burials were found, all in poor condition because of dampness. Outstanding was an unusual bird pendant of hematite with crystal eyes set into drilled sockets with piñon gum. Forty-two bowls were reconstructed from the sherds found.

In the summer of 1929 Mr. and Mrs. Harold S. Gladwin and associates of Gila Pueblo, Globe, Ariz., assisted by Deric Nusbaum, conducted an archeological survey of small-house ruins on Chapin Mesa and in the canyon heads along the North Rim. The survey covered 250 sites. One hundred sherds were collected from each site and studied to identify the pottery types, the sequence of their development, and their relationship to pottery types of other southwestern archeological areas.

The forest fire of 1934 revealed many hitherto unknown ruins. Two splendid watchtowers were found on the west cliff of Rock Canyon. In a small area at the head of Long Canyon 10 new Early Pueblo ruins were located and no doubt scores of others will be found upon more careful search. In the heads of the small canyons many dams and terraces were noted.

In the stabilization program that was carried on in 1934-35 a number of artifacts were found. A certain amount of debris had to be moved in order that the weakened walls and slipping foundations might be strengthened and varied finds resulted. Axes, bone awls, sandals, pottery, planting sticks, and similar articles were most common, but a few burials were also found.

In August 1934 the undisturbed skeleton of an old woman was found on the bare floor of a small ruin just across the canyon from the public camp grounds. This skeleton, of particular importance because of fusion of the spinal column, had apparently remained exposed and undisturbed through more than seven centuries.

Because of the fact that no detailed, comprehensive survey has ever been made of the archeological resources of the park, the findings of new ruins, artifacts, and human remains are more or less regularly reported at the park museum.

PREHISTORIC INHABITANTS OF THE MESA VERDE

The so-called "Mesa Verde cliff dwellers" were not the first of the prehistoric southwestern cultures, nor were they the first human occupants of the natural caves that abound in the area of the park. Centuries before the cliff-dweller culture with its complex social organizations, agriculture, and highly developed arts of masonry, textiles, and ceramics, it is thought that small groups of primitive Mongoloid hunters crossed from the northeastern peninsula of Asia to the western coast of Alaska. The Bering Strait, with but 60 miles of water travel, offered the safest and easiest route.

Just when these migrations to the east had their origin and how long they continued cannot definitely be said, but it is thought the earliest Mongoloid hunters were in northwestern America about twelve to fifteen thousand years ago. When Columbus "discovered" America the continent was inhabited from Alaska to the Strait of Magellan and from the Pacific to the Atlantic coasts.

For perhaps several thousand years following the first migrations little of great significance developed. There undoubtedly was cultural progress, but it was slow, and in the long perspective of time its evidences are hardly discernible. With the knowledge and benefits of agriculture, which was probably developed first in Mexico, hunting gave way to husbandry, nomadism to sedentary life, and there followed a great period of change and advancement. The introduction of corn or Indian maize into what is now the southwestern United States may be called the antecedent condition for all advanced cultures of the area.

Evidence has not yet been established that the first of the maize-growing Indians of the Southwest were permanent occupants of the Mesa Verde. Nevertheless, in the Cliff Palace cave, well below the horizon or floor level of the cliff dwellers, archeologists have found a yucca fiber sandal of a distinctive type which is associated only with the first agricultural civilization. From this evidence it would be reasonable to assume that the caves of Mesa Verde at least offered temporary shelter, if not permanent homes, to the people of this period.

The earliest culture so far definitely identified as having permanent habitation on the Mesa Verde is the Basket Maker III or the Second Agricultural Basket Maker first found in Step House cave on the west side of the park below the debris of the latter cliff-house occupation. Recent excavations and archeological surveys furnish conclusive evidence that the second agricultural people were most numerous in the area now included in this national park, and they constructed their roughly circular subterranean rooms not only in the sandy floor of the caves but also in the red soil on the comparatively level mesas separating the numerous canyons. Late Basket Maker House A, formerly known as Earth Lodge A, is an excellent example of this early type of structure. Up to this time excavations have failed to uncover a single house structure of this type not destroyed by fire.

These early inhabitants made basketry, excelled in the art of weaving, and it is believed were the first of the southwestern cultures to invent fired pottery. The course of this invention can be traced from the crude sun-dried vessel tempered with shredded cedar bark to the properly tempered and durable fired vessel.

Then followed a long development in house structure, differing materially from this earlier type. Horizontal masonry replaced the cruder attempts of house-wall construction; rectangular or squarish forms replaced the somewhat circular and earlier type; and gradually the single-room structure was grouped in ever-enlarging units which assumed varying forms of arrangement as the development progressed. The art of pottery making improved concurrently with the more complex house structure. This later period represents the intermediate era of development from the crude Late Basket Maker dwellings to the remarkable structures of the "Cliff House Culture."

During this period of transition new people penetrated the area. The Basket Makers throughout the course of their development were consistently a long-headed group. The appearance of an alien group is recorded through the finding of skeletons with broad or round skulls and a deformed occiput. These new people, the Pueblos, took over, changed, and adapted to their own needs the material culture of the earlier inhabitants.

The cliff dwellers were not content with the crude buildings and earth lodges that satisfied as homes during earlier periods of occupancy. For their habitations they shaped stones into regular forms, sometimes ornamenting them with designs, and laid them in mud mortar, one on another. Their masonry has resisted the destructive forces of the elements for centuries.

The arrangement of houses in a cliff dwelling the size of Cliff Palace is characteristic and is intimately associated with the distribution of the social divisions of its former inhabitants.

The population was composed of a number of units, possibly clans, each of which had its more or less distinct social organization, as indicated in the arrangement of the rooms. The rooms occupied by a clan were not necessarily connected, although generally neighboring rooms were distinguished from one another by their uses. Thus, each clan had its men's room, which is ceremonially called the "kiva." Each clan had also one or more rooms, which may be styled the living rooms, and other enclosures for granaries. The corn was ground into meal in another room containing the metate set in a stone bin or trough. Sometimes the rooms had fireplaces, although these were generally in the plazas or on the housetops. All these different rooms, taken together, constituted the houses that belonged to one clan.

The conviction that each kiva denotes a distinct social unit, as a clan or a family, is supported by a general similarity in the masonry of the kiva walls and that of adjacent houses ascribed to the same clan. From the number of these rooms it would appear that there were at least 23 social units or clans in Cliff Palace.

Apparently there is no uniformity or prearranged plan in the distribution of the kivas. As religious belief and custom prescribed that these rooms should be subterranean, the greatest number were placed in front of the rectangular buildings where it was easiest to construct them. When necessary, because of limited space or other conditions, kivas were also built far back in the cave and inclosed by a double wall of masonry, with the walls being spaced about two and a half to three feet apart. The section between the walls was then backfilled with earth or rubble to the level of the kiva roof. In that way the ceremonial structure was artificially made subterranean, as their beliefs required.

In addition to their ability as architects and masons, the cliff dwellers excelled in the art of pottery making and as agriculturists. Their decorated pottery—a black design on pearly white background—will compare favorably with pottery of the other cultures of the prehistoric Southwest.

As their sense of beauty was keen, their art, though primitive, was true; rarely realistic, generally symbolic. Their decoration of cotton fabrics and ceramic work might be called beautiful, even when judged by our own standards. They fashioned axes, spear points, and rude tools of stone; they wove sandals, and made attractive basketry.

The staple product of the cliff dwellers was corn; they also planted beans and gourds. This limited selection was perhaps augmented by piñon nuts and yucca fruit—indigenous products found in abundance. Nevertheless, successful agriculture on the semiarid plateau of the Mesa Verde must have been dependent upon hard work and diligent efforts. Without running streams irrigation was impossible and success depended upon the ability of the farmer to save the crop through the dry period of June and early July.

Rain at the right time was the all-important problem, and so confidently did they believe that they were dependent upon the gods to make the rain fall and the corn grow that they worshiped the sun as the father of all life and the earth as the mother who brought them all their material blessings.

From Dr. A. E. Douglass's tree-ring chronology the earliest date so far established for the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings is 1066 A. D. and the latest date 1274 A. D. While it should not be imagined that these are the all-inclusive dates representing the total time of the cliff-dweller culture, it is interesting to note that this same tree-ring story tells us that a great drought commenced in 1276 and extended for a 23-year period to 1299. It may logically be presumed that the prehistoric population was gradually forced to withdraw from the area as the drought continued and to establish itself near more favorable sources of water supply.

The so-called "Aztec ruin", which is situated on the banks of the Animas River in northwestern New Mexico, substantiates this hypothesis of the voluntary desertion of the cliff dwellings. In this ruin is found unmistakable evidence of a secondary occupation which has been definitely identified as a Mesa Verde settlement.

It is thought that certain of the present-day Pueblo Indians are descendants, in part at least, of the cliff dwellers. Many of these Indian towns or pueblos still survive in the States of New Mexico and Arizona, the least modified of which are the villages of the Hopi, situated not far from the Grand Canyon National Park.

FAUNA AND FLORA

The fauna and flora of Mesa Verde should be particularly interesting to visitors. A combination of desert types from the lower arid country and mountain types, usually associated with regions of higher rainfall, occur here. The desert types are highly specialized to cope with their environment, particularly the plant and smaller animal life.

Rocky Mountain mule deer are perhaps the only big game to be found abundantly in the park. They are often seen. Their numbers in the park, however, vary greatly according to the season. It is hoped to reintroduce the native species of Rocky Mountain bighorn, as soon as range sufficient for the needs of this species has been added to the park.

Cougars, or mountain lions, are part of the wildlife of the park and, strange to say, are occasionally seen in broad daylight. In other national parks these animals are rarely seen even by rangers.

Coyotes and foxes are not as numerous as they once were on the mesa. As a result, many of the smaller animals such as porcupines and prairie dogs have greatly increased. Wildcats are fairly common but are only occasionally seen.

Game birds are represented by the dusky grouse and scaled quail, both desert types. No wild turkeys are found in the park now, although it is believed that they were once there. Fragments of bones discovered in the ruins indicate that the cliff dwellers kept turkeys. Whether these were wild turkeys from the mesa or birds brought in from elsewhere is a question that has not as yet been answered. At present the reintroduction of wild turkeys to Mesa Verde is under consideration.

Among the most interesting animal residents of Mesa Verde are the lizards. Some of these are: the horned lizard, the western spotted or earless lizard, the collared lizard, the striped race-runner, utas, rock swifts, and sagebrush swifts.

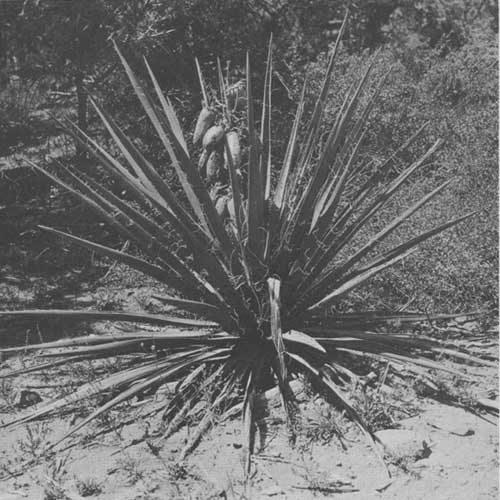

Although Mesa Verde receives considerably more rainfall than true desert areas, vegetation is fairly sparse at the best and is generally of the arid type. Cacti of a number of varieties flourish but are conspicuous only in May and June when they bloom. Piñon pine, juniper, Douglas fir, and western yellow pine represent most of the large evergreens. Oregon grape, yucca, and mistletoe (on the junipers) are some of the other plants found over the area. Nearer the springs and water courses vegetation is much more luxurious, but unfortunately these spots are far below the level of the mesa and are mostly on privately owned land.

A yucca plant in fruit (Yucca baccata).

HOW TO REACH THE PARK

BY AUTOMOBILE

Mesa Verde National Park may be reached by automobile from Denver, Colorado Springs, Pueblo, and other Colorado points. Through Pueblo one road leads to the park by way of Canon City, from where one may look down into the Royal Gorge, the deepest canyon in the world penetrated by a railroad and river. This road passes through Salida and on through Gunnison and Montrose, and then south through Ouray, Silverton, and Durango. This route passes through some of Colorado's most magnificent mountain scenery. Another road leads south from Pueblo through Walsenburg, across La Veta Pass, on through Alamosa, Del Norte, Pagosa Springs, and Durango, crossing Wolf Creek Pass en route. Both roads lead west from Durango to Mancos and on into the park.

Motorists coming from Utah turn southward from Green River or Thompsons, crossing the Colorado River at Moab, proceeding southward to Monticello, thence eastward to Cortez, Colo., and the park.

From Arizona and New Mexico points, Gallup, on the National Old Trails Road, is easily reached. The auto road leads north from Gallup through the Navajo Indian Reservation and a corner of the Ute Indian Reservation. At Shiprock Indian Agency, 98 miles north of Gallup, the San Juan River is crossed.

BY RAILROAD

Mesa Verde National Park is approached by rail both from the north and from the south: From the north via the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad main transcontinental line through Grand Junction, and branch lines through Montrose and Durango; from the south via the main transcontinental line of the Santa Fe Railroad through Gallup, N. Mex.

The lines of the Denver & Rio Grande Western System traverse some of the most magnificent scenery of the Rocky Mountain region, a fact which gives the journey to Mesa Verde zestful travel flavor. Two main-line routes are provided to the Grand Junction gateway.

The Royal Gorge Route goes through the Grand Canyon of the Arkansas, now spanned by an all-steel suspension bridge, 1,053 feet above the tracks in the Royal Gorge. This route crosses Tennessee Pass (altitude, 10,240 feet) and follows the Eagle River to its junction with the Colorado River at Dotsero, thence to Grand Junction.

Service was inaugurated in June 1934 via the new James Peak Route of the D. & R. G. W., utilizing the Moffat Tunnel (altitude at apex, 9,239 feet), 6.2-mile bore which pierces the Continental Divide, 50 miles west of Denver. This route follows the Colorado River from Fraser, high on the west slope of the continent, through Byers Canyon, Red Gorge, Gore Canyon, and Red Canyon, thence over the Dotsero Cut-off to Dotsero, where it joins the Royal Gorge Route. The new line saves 175 miles in the distance from Denver to Grand Junction.

MOTOR TRANSPORTATION

The Rio Grande Motor Way, Inc., of Grand Junction, Colo., from June 15 to September 15, operates a daily motor service from Grand Junction, Delta, Montrose, Ouray, Silverton, Durango, and Mancos, Colo., to Spruce Tree Lodge in Mesa Verde National Park. This motor bus leaves Grand Junction at 7:15 a. m., via the scenic Chief Ouray Highway, stopping en route at other places mentioned, crossing beautiful Red Mountain Pass (altitude, 11,025 feet), arriving at Spruce Tree Lodge at 7 p. m. The stage leaves the park at 7 a. m., arriving at Grand Junction at 5:40 p. m.

The round-trip fare between Grand Junction and the park is $26.56 if four or more persons make the trip, and increases as the number of passengers decreases.

Entrance to Mesa Verde from the south through Gallup, N. Mex., via the Navajo and Southern Ute Indian Reservations, is growing constantly in convenience and popularity: Hunter Clarkson, Inc., with headquarters at El Navajo Hotel, in Gallup, operates two-day round trip light sedan service, leaving Gallup at 8 a. m. on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and returning to Gallup at 6 p. m. on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays.

This service permits the visiting of ruins in the park, in accordance with regular schedules, on the afternoon of the first day and on the morning of the second. The round trip fare per person (360 miles) is $25. A minimum of two passengers is required. Fare for children, five and under twelve, is $12.50. Meals and hotel accommodations en route or at the park are not included. El Navajo Hotel, operated by Fred Harvey, offers excellent overnight accommodations at Gallup.

The Cannon Ball Stage operates bus service from Gallup, via Shiprock and Farmington, to Durango, where connection may be made with the motor bus of the Rio Grande Motor Way, Inc., for the trip from Durango to the park. The Cannon Ball Stage bus leaves Gallup each day at 11:30 a. m., arriving at Durango at 4:45 p. m. Returning it leaves Durango at 8 a. m. and arrives at Gallup at 1 p. m. The fare from Gallup to Durango is $6 one way and $10.80 for the round trip.

ADMINISTRATION

The Mesa Verde National Park is under the exclusive control of the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior, which is authorized to make rules and regulations and to establish such service as it may deem necessary for the care and management of the park and the preservation from injury or spoliation of the ruins and other remains of prehistoric man within the limits of the reservation.

The National Park Service is represented in the actual administration of the park by a superintendent, who is assisted in the protection and interpretation of its natural and prehistoric features by a well-trained staff. The present superintendent is Jesse L. Nusbaum, and his post-office address is Mesa Verde National Park, Colo.

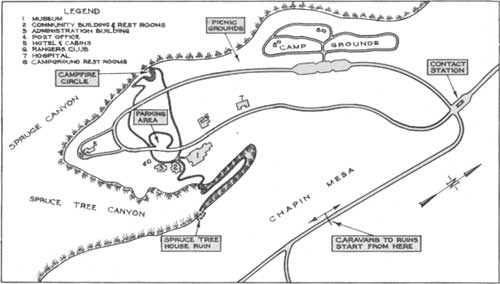

Headquarters Area.

The park season extends from May 15 to October 15, complete lodging and food accommodations and automobile stage service being available from June 15 to September 15. Informal lodging and meal accommodations are provided during the remainder of the park season.

Exclusive jurisdiction over the park was ceded to the United States by act of the Colorado Legislature approved May 2, 1927, and accepted by Congress by act approved April 25, 1928. There is a United States Commissioner at park headquarters.

Telegrams sent prepaid to Mancos, Colo., will be phoned to addressee at park office. The post-office address for parties within the park is Mesa Verde National Park, Colo.

EDUCATIONAL SERVICE

Educational service, carefully planned to provide each visitor with an opportunity to interpret and appreciate the features of the Mesa Verde, is provided, without charge, by the Government. This service is directed by the park naturalist, who is assisted by a group of ranger naturalists.

GUIDED TRIPS TO THE RUINS

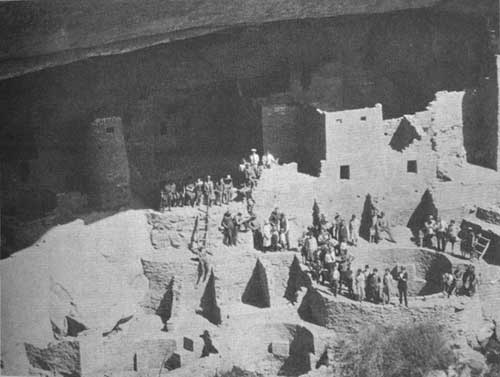

During the season visitors are accompanied from the park museum to the various ruins by competent ranger naturalists. These men, well trained in the social and biological sciences, make it their duty to help the visitor understand the natural and archeological features of the Mesa Verde. Because of the need of protecting the ruins and the somewhat devious trails by which they are reached, no one will be allowed to enter any ruin except Spruce Tree House unless accompanied by a ranger.

CAMP-FIRE TALKS

Each evening at 8 o'clock informal talks are given at the camp-fire circle near park headquarters. The superintendent, the park naturalist, and members of the educational staff give talks on the archeology of the region. Visiting scientists, writers, lecturers, and noted travelers often contribute to the evening's entertainment. After the talks six of the best singers and dancers among the Navajo Indians employed in the park can usually be persuaded, by modest voluntary contributions on the part of the visitors, to give some of their songs and dances.

Competent ranger naturalists accompany visitors to the ruins.

PARK MUSEUM

The park museum houses very important and comprehensive collections of excavated cliff-dweller and basket maker material, as well as restricted collections of arts and crafts of modern Indians of the Southwest. These collections have been assembled through the conduct of excavations within the park and through loan or gift of materials by park friends or cooperating institutions. This material is arranged in a definite chronological order. By following through from the earliest culture to those of the present time a clear and concise picture of the former material cultures of the Mesa Verde and surrounding regions may be obtained.

One room has been set aside for natural history exhibits exemplifying the geology, fauna, and flora of this peculiar mesa-canyon country.

REFERENCE LIBRARY

A part of the museum is given over to an excellent reference library and reading room. This library consists of books on archeology and related natural history subjects pertaining to this interesting region. Visitors have access to these books on application to the museum assistant who is in charge. These books may not be removed from the reading room.

FREE PUBLIC CAMP GROUNDS

The new public camp grounds are located in the piñons and junipers on the rim of Spruce Canyon only a few hundred feet from Spruce Tree Lodge and park headquarters. Individual party campsites have been cleared, and a protecting screen of shrubbery contributes to their privacy. Each site is provided with a fireplace, a table with seats, and a large level place for a tent. Good water has been piped to convenient places, and cut wood is provided without charge. Toilet facilities, showers, and laundry tubs are also provided. A ranger is detailed for duty in the camp grounds.

Leave your campsite clean when you have finished with it.

Do not drive cars on, or walk over the shrubbery.

The camp ground facilities at Mesa Verde have been greatly improved and expanded through the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Provisions for campers are obtainable at reasonable prices in any of the nearby towns. Groceries, gas, and oil can also be purchased at Spruce Tree Lodge.

HORSEBACK AND HIKING TRIPS

Visitors who view the Mesa Verde from the automobile roads gain but an inkling of the weird beauty and surprises that this area holds for the more adventurous. Horseback and hiking trips along the rim rocks and into the canyons lead to spectacular ruins not seen from any of the roads. Such great ruins as Spring House, Long House, Kodak House, Jug House, Mug House, and Step House, as well as all of the ruins in the more remote canyons, can be reached by trail only. Each turn of the trail reveals entrancing vistas of rugged canyons, sheer cliffs, great caves, hidden ruins, distant mountains, tree-covered mesas, and open glades.

In making these trips it is important that the hiker prepare himself with proper footwear, as the trails are very precipitous in places.

A party off for the less-frequented trails. Grant photo.

HOSPITAL AND MEDICAL SERVICE

There is an excellent hospital at park headquarters where medical and surgical service is provided to care for all emergency cases. Prices are regulated by the Secretary of the Interior.

ACCOMMODATIONS AND EXPENSES

At Spruce Tree Lodge, situated among the piñons and junipers over looking Spruce, Spruce Tree, and Navajo Canyons, cottages and comfortable floored tents may be rented at prices ranging from $0.75 to $2 per day a person for accommodations only, and from $4.50 to $5.75 per day including meals. Meals, table d'hote and a la carte, at reasonable prices. Children: No charge under 3; half rates from 3 to 8. The official season for Spruce Tree Lodge is from June 15 to September 15.

The company also operates, for visitors who do not care to use their own cars or are without private transportation, automobile service to various ruins for $1 each, round trip. A special evening trip to Park Point to see the spectacular sunset from the highest point in the park is $1.50 per person.

OUT-OF-SEASON ACCOMMODATIONS

Before June 15 and after September 15, cabins may be rented from the caretaker of Spruce Tree Lodge at the regular rates. Meals, with breakfast 50 cents, and luncheon and dinner 75 cents, may be had at the Government dining hall. In nearby towns, less than an hour's drive from park headquarters, accommodations are also obtainable.

PACK AND SADDLE ACCOMMODATIONS

Saddle horses, especially trained for mountain work, may be rented from the Mesa Verde Pack & Saddle Co. For short trips the rental is $1 for the first hour and 50 cents for each additional hour. For short 1-day trips for three persons or more the cost is $3.50 each; two persons $4 each; one person $6. Longer 1-day trips for experienced riders are available at $2 per person more than the rate for the shorter 1-day trips. All prices include guide service, and a slicker, canteen, and lunch bag are provided with each horse. Arrangements should be made the evening before the trip is taken.

PACK TRIPS

Nonscheduled pack trips to the more remote sections of the park may be arranged (2 days' notice is required) at prices ranging from $9 a day each for parties of five or more to $15 a day for one person. This includes a guide-cook and furnishes each person with one saddle horse, one pack horse, bed, tent, canteen, slicker, and subsistence for the trip. Three days is the minimum time for which these trips can be arranged.

REFERENCES2

2For complete bibliography apply at the park museum or write to the Superintendent, Mesa Verde National Park.

CHAPIN, F. H. The Land of the Cliff Dwellers.3 W. B. Clarke & Co., Boston, Mass. 1892. 187 pages.

DOUGLASS, DR. ANDREW ELLICOTT. The Secret of the Southwest Solved by the Talkative Tree Rings, in National Geographic Magazine, December 1929.3

FARIS, John T. Roaming the Rockies. Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., New York. 1930. Illustrated. 333 pages. Mesa Verde on pp. 193-203.

FEWKES, J. WALTER. Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park: Spruce Tree House.3 (Bureau of American Ethnology Bull. 41, 1909. 57 pages, illustrated.) (Out of print.)

______. Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park: Cliff Palace.3 (Bureau of American Ethnology Bull. 51, 1911. 82 pages, illustrated.) (Out of print.)

-=______. Excavation and Repair of Sun Temple, Mesa Verde National Park.3 (Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. 1916. 32 pages, illustrated.) (Out of print.)

______. A Prehistoric Mesa Verde Pueblo and Its People.3 (Report of the Secretary of the the Smithsonian Institution. 1917. 26 pages.) (Out of print.)

______. Prehistoric Villages, Castles, and Towers of Southwestern Colorado.3 (Bureau of American Ethnology Bull. 70. 1919. 79 pages text, 33 plates.)

GILLMOR, FRANCES, and WETHERILL, LOUISA WADE. Traders to the Navahos.3 Houghton Muffin Co., Boston and New York. 1934. Illustrated, 265 pages. Describes discovery of cliff dwellings by Wetherill brothers.

HOLMES, WILLIAM H. Report on Ancient Ruins in Southwestern Colorado Examined During Summers of 1875 and 1876. (Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories (Hayden), Tenth Report, 1876, pp. 381-408, illustrated.)

ICKES, ANNA WILMARTH. Mesa Land.3 Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston and New York, 1933. Illustrated. 228 pages. Southwest in general. Mesa Verde, pp. 100-101.

INGERSOLL, ERNEST. Reprint, first article. Mancos River Ruins, New York Tribune. Nov. 3, 1874; in Indian Notes, vol. 5, no. 2, April 1928, pp. 183-206, Museum of American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York.3

JACKSON, W. H. The Pioneer Photographer.3 World Book Co., 1929.

JEFFERS, LE ROY. The Call of the Mountains. 282 pages, illustrated. Dodd, Mead & Co., 1922. Mesa Verde on pp. 96-Ill.

KANE, J. F. Picturesque America. 1935. 256 pp., illustrated. Published by Frederick Gumbrecht, Brooklyn, N. Y. Mesa Verde on pp. 121-124.

KIDDER, ALFRED VINCENT. An introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology.3 300 pages, illustrated. Yale University Press, 1924. Mesa Verde on pp. 58-68.

______. Beautiful America—Our National Parks. 1924. 160 pages pictorial views Beautiful America Publishing Corporation, New York City. Mesa Verde views pp. 58-68.

MILLS, ENOS A. Your National Parks. 1917. 532 pages, illustrated. Mesa Verde National Park on pp. 161-174; 488-490.

MORRIS, ANN AXTELL. Digging in the Southwest.3 Doubleday Doran Co., 1933. Readable account of the trade secrets of a southwestern archeologist.

NORDENSKIÖLD, G. The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde.3 1893. 171 pages, illustrated.

NUSBAUM, DERIC. Deric in Mesa Verde.3 1926. Illustrated. G. P. Putnam's Sons. Knickerbocker Press.

ROLFE, MARY A. Our National Parks.3 Book One. A supplementary reader on the national parks for the fifth and sixth grade students. Benj. H. Sanborn & Co. 1927. Illustrated. Mesa Verde on pp. 221-234.

YARD, ROBERT STERLING. The Top of the Continent. 1917. 244 pages, illustrated. Mesa Verde National Park on pp. 44-62.

______. The Book of the National Parks. 1926. 444 pages, illustrated. Mesa Verde National Park on pp. 284-304.

3Copies in Mesa Verde Museum Library.

|

Glimpses of Our National Parks. An illustrated booklet of 92 pages containing descriptions of the principal national parks. Address the Director, National Park Service, Washington, D. C. Free. Recreational Map. Shows both Federal and State reservations with recreational opportunities throughout the United States. Brief descriptions of principal ones. Free. Fauna of the National Parks. Series No. 1. By G. M. Wright, J. S. Dixon, and B. H. Thompson. Survey of wildlife conditions in the national parks. 157 pages, illustrated. Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 20 cents. Fauna of the National Parks. Series No. 2. By G. M. Wright and B. H. Thompson. Wildlife management in the national parks. 142 pages, illustrated. Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. 20 cents. Map of Mesa Verde National Park; 43 by 28 inches; scale, one-half mile to the inch. United States Geological Survey, Washington, D. C. Price 20 cents. Panoramic View of Mesa Verde National Park; 22-1/2 by 19 inches; scale, three-fourths mile to the inch. Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price, 25 cents. National Parks Portfolio. By Robert Sterling Yard. Cloth bound and illustrated with more than 300 beautiful photographs of the national parks. Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price $1.50. Booklets about the national parks listed below may be obtained free of charge by writing The National Park Service, Washington, D. C.

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1936//sec3.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010