|

DEATH VALLEY

Guidebook 1940 |

|

| OPEN ALL YEAR |

|

Death Valley NATIONAL MONUMENT CALIFORNIA |

||

|

BEAR POPPY

| ||||

DEATH VALLEY National Monument was created by Presidential proclamation on February 11, 1933, and enlarged to its present dimensions on March 26, 1937. Embracing 2,981 square miles, or nearly 2 million acres of primitive, unspoiled desert country, it is the second largest area administered by the National Park Service in the United States proper.

Famed as the scene of a tragic episode in the gold-rush drama of '49, Death Valley has long been known to scientist and layman alike as a region rich in scientific and human interest. Its distinctive types of scenery, its geological phenomena, its flora, and climate are not duplicated by any other area open to general travel. In all ways it is different and unique.

The monument is situated in the rugged desert region lying east of the High Sierra in eastern California and southwestern Nevada. The valley itself is about 140 miles in length, with the forbidding Panamint Range forming the western wall and the precipitous slopes of the Funeral Range bounding it on the east. Running in a general northwesterly direction, the valley is narrow in comparison to its length, ranging from 4 miles or less in width at constricted points to perhaps 16 miles at its widest part. It is a region of superlatives. Approximately 550 square miles of the valley floor are below sea level; and Badwater, 280 feet below that plane, is the lowest land in the entire Western Hemisphere. Telescope Peak, towering 11,325 feet above the valley floor, probably stands higher above its immediate surroundings than any other mountain in the 48 States. Death Valley held, until quite recently, a world's record for high temperatures, and it is one of the driest places in the West. In a standard thermometer shelter at Furnace Creek a maximum air temperature of 134° F in the shade has been recorded. On the salt flats near Badwater, in the deepest part of the valley, it has probably been hotter still. These extreme temperatures, of course, are unknown except during the summer months. Through the winter season, from late October until May, the climate is ideal. The days are warm and sunny for the most part, and the nights are cool and invigorating. The valley is famous for consistently fair weather, lack of rainfall and extremely low humidity. One record for an entire year showed 351 clear days; and the average annual precipitation over a period of many years is 1.4 inches.

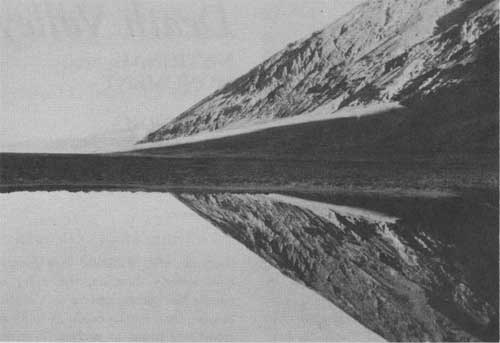

BLACK MOUNTAIN REFLECTED IN BADWATER, 280 FEET BELOW SEA LEVEL

HISTORY

The first recorded discovery of Death Valley is in 1849. A conjecture for its remaining unexplored until that date is that possibly the aborigines had warned any would-be discoverers to stay away from "Tomesha" (meaning "ground-afire"), the Indian name for Death Valley.

The Spaniards of early California may have been in Death Valley, but if so, no record remains.

It is also possible that John Charles Fremont, in 1844, saw the extreme southern end from where his party camped; but it remained for a band of half-starved emigrants, pushing westward on a supposed shortcut to the newly discovered gold fields, actually to discover Death Valley in the winter of 1849. They were lost in the wilderness, hungry and sick of the trail, and the wide salt floor of the valley with the towering Panamints beyond were a last blow to their morale. Losing all semblance of order, the train split up in every direction. Some went up the valley; some turned to the south. The Jayhawker party and a few others, abandoning most of their equipment, found their way eventually over passes in the Panamints, and crossed the Panamint Valley and the Mojave Desert. Suffering tremendous hardships, and losing a number of their members, they finally reached the coast.

The Bennett-Arcane party, however, crossed the salt flats and camped for 3 weeks in the vicinity of what is now called Bennetts Well. Manly and Rogers were sent on ahead in a desperate attempt to find a way to civilization and to bring help if possible. Making a trip of heroic proportions, they finally returned and led their party through to the coastal region without further loss of life. Pausing on the crest of the Panamints, the weary emigrants looked back across the valley, that tremendous barrier that had caused so much privation and suffering, and cried, "Good-bye, Valley of Death." Thus Death Valley was christened. It has never known another English name.

In the next few years some of the Forty-niners, undaunted, returned as guides or on their own to prospect, and to search for the Lost Gunsight silver lode. Gradually the country became better known. Panamint, and later Skidoo, Greenwater, and other picturesque mining camps lived their short lives and died, leaving only tumbled shacks, weathered timbers and broken bottles to mark their sites. Sometimes the prospectors struck it rich in the rugged peaks and barren canyons that shut the valley in from the surrounding, less forbidding desert. Itinerant prospectors prodded their burros from one spring to the next, following Indian trails or beating out new tracks, and crossed and recrossed the ranges from one end of the valley to the other. Sometimes they were careless or not acquainted with the country. They missed the springs, lost their burros, or lingered too long on the floor of the valley in summer. Their carcasses, dried and picked clean by kit-fox and raven, were found eventually and buried beside the trail.

Borax was finally responsible for the partial taming of the valley. In the 80's, "cotton-ball" borax was refined at the old Harmony Mill, and freighted over agonizing miles of desert in huge, high-wheeled wagons drawn by strings of 20 mules. A railroad was built to the edge of the valley when richer deposits were discovered. Adventurous visitors drove their cars into the valley, cursed its then abominable roads, but came again. With all America on wheels, it was inevitable that Death Valley would come into its own as a national playground.

Development of the monument has taken place rapidly. The construction of monument roads and trails, buildings and campgrounds, water supply and sanitation, has been accomplished through CCC enrollee labor, supervised by National Park Service experts. The aim of the Service has been to make Death Valley accessible and safe, without altering its rugged beauty and charm.

20-MULE TEAM HAULING BORAX ACROSS DEATH VALLEY IN THE '80s

INDIANS

For centuries the Death Valley region has been inhabited by a small offshoot of the Shoshone Nation, called the Panamint Indians. Driven from their homes to the North many generations back, the Panamints gravitated to Death Valley, where they were least molested by their more warlike brother. Capable of great endurance, ingenious in the utilization of every edible or otherwise useful plant, eating any animal that they could shoot or catch, following the seasons in incessant migration from valley floor to mountain crest, they managed to survive. With the coming of the white man their numbers were decimated by disease and loss of old customs and arts; but the damage wrought by civilization is being repaired. A model Indian village has been constructed just south of Furnace Creek Ranch; garden plots have been made available; old arts are being revived; and a trading post will be established. Once more the Panamints will be a self-sustaining tribe.

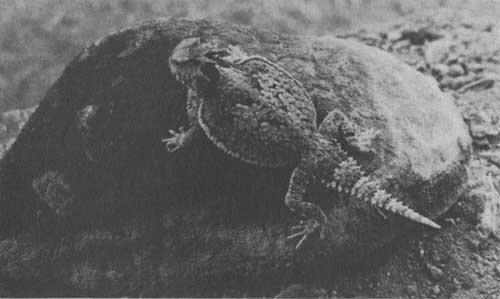

THE "HORNED TOAD," BLENDING WITH THE SAND AND ROCKS, OFTEN REMAINS

UNSEEN

WILDLIFE

Animal life is surprisingly abundant in the monument, in contrast to the popular belief that nothing lives or grows in Death Valley. True, few animals are seen by the casual visitor, because most of them are nocturnal, and all are shy. Many are so adapted to desert conditions that they obtain all the moisture needed from their food; and consequently only the salt flats, with no vegetation, are barren of all life.

Some 26 species of mammals have been recorded below the sea level contour, and many more live only at higher elevations. The most commonly seen rodent is the antelope ground squirrel, but kangaroo rats, wood rats and several other types inhabit the mesquite thickets and even the scantily vegetated rock slopes and alluvial fans. Several carnivores, including the kit-fox and coyote, are occasionally glimpsed along the roads in the evening.

In the high country are several hundred head of the desert bighorn. On the verge of extinction in other parts of their range, they are apparently increasing in the monument under rigorous protection. Wild burros are numerous, particularly in the Panamint Range. They were first introduced by prospectors as pack animals, but have long since gone wild and increased in numbers.

Lizards of a dozen or more species are abundant, except for a short period of hibernation in the winter. They range in size from the huge but harmless chuckawalla to the tiny banded gecko, weak and thin-skinned and often mistaken for the young of some larger kind. Snakes are comparatively rare, the valley floor being too hot for most species during the summer months.

Approximately 170 species of birds have been recorded below sea level. Most of them are only migrants or winter visitors, and include a surprisingly large number of water birds; but 14 species make the valley floor their permanent home. The big black desert raven is the one most commonly noted. Insects abound but almost never prove annoying. Even fish are not left out of the faunal picture, as two species of Cyprinodons, or "desert sardines," live in the saline waters of Salt Creek and Saratoga Springs.

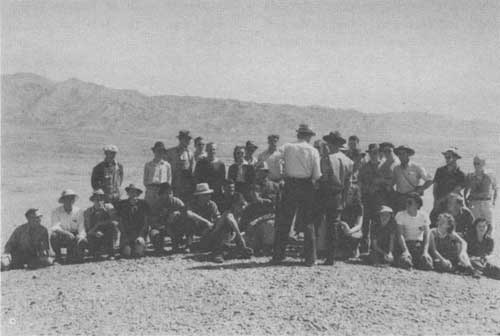

STUDYING THE NATURAL PHENOMENA WITH THE RANGER NATURALIST

PLANTS

More than 560 species of native plants are known from the Death Valley watershed in the monument. Since the Death Valley expedition of 1891 this region has been famous for the number of new and rare species discovered here; and more are being found as time goes on. In spite of extreme desert conditions it is only on the Devils Golf Course and the alkali flats that nothing whatever grows. Even here, at the very edge of the salt, is found the light green iodine-bush, the plant that is more resistant than any other to salt and alkali. Over most of the low country there is a scattered growth of drought resisting shrubs, interspersed with some herbaceous perennials.

Under the right conditions, during the springs following heavy winter rains, the Death Valley flower show is worth traveling many miles to see. Then the desert blossoms like a garden. Dozens of varieties of annuals carpet the fans, washes and canyons. These include, among many others, nine evening primroses, several phacelias, the desert sunflower, and the exquisite "five-spot," or Chinese lantern. They spring up quickly, bloom and produce their seeds, then wither and die with the coming of summer. The scattered seeds lie in the dust-dry soil to await the favoring rains of some following year.

Perhaps the most typical of the many shrubs are the desert holly and the Covillea, or creosote bush, both of which thrive on the alluvial fans and elsewhere. The beautiful Death Valley sage, known only from this region, grows in shady, dry canyons. A dozen species of cacti include the beaver-tail, cotton-top, and cholla. Cactus flowers add their tones to the general symphony of color in the spring. Among the herbaceous perennials are the rare bear poppy, with peculiar bluish foliage covered with long, white hairs; and the wet-leaf, whose leaves are always moist, even under the burning sun of the dry washes where it grows. Several species of desert mariposa lilies bloom in the high country, along with the mallow, lupine, astragulus, and many others, providing a flower display that lasts well into the summer.

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about Death Valley plants is the strange provisions by which the shrubs keep alive during the burning heat and dryness of summer. They reduce the evaporation of moisture from their surface in many ways; by having no leaves, as in most of the cacti; very small leaves, or leaves reduced to scales; leaves that are varnished, or that drop off with the coming of summer; and leaves that have a dense covering of scales, as in the desert holly, Death Valley sage, and others. Some shrubs combine two or three of these adaptations, and most of them have long roots which penetrate deeply into the moister soil far below the surface.

Many of the plants native to the valley may be seen growing at the nursery near the monument headquarters. Here plants are grown for use in replanting and landscaping. The nursery is open to the public from 9 to 11 in the morning and from 1 to 4 in the afternoon. Supplementary pamphlets on the botany of the monument are available at the nursery or the office of the naturalist.

GEOLOGY

Death Valley has often been described as a vast geologic museum, only a small portion of which has been catalogued. Formerly so inaccessible and forbidding, it has been little studied; and it will be several years before more than a superficial understanding of its geologic phenomena can be obtained. Enough is already known to indicate that a remarkable geologic story can eventually be told. For a more comprehensive and detailed account the reader is referred to the supplementary pamphlet available at the office of the park naturalist, and to the more technical papers listed therein.

The rock column in the monument represents a tremendous span of geologic time, including all the great divisions, called eras, and even the subdivisions or periods of most of them. It is one of the most complete geologic sections in America. If the strata were pieced together and restored to their proper sequence, their total thickness would probably exceed 12 miles. Recurrent earth movements have been so intense, however, that the rock masses form a jumble of displaced crustal blocks, isolated from one another by folding, faulting, tilting, igneous intrusion and burial under more recent sediments. At any one locality, therefore, the sequence is incomplete, and can be understood only by examination of the area as a whole.

The oldest geologic era, the Archeozoic, is represented by the basal rocks of the region. Great thicknesses of gneiss, schist, quartzite, marble, and other types of metamorphic (altered) rocks are exposed over large areas in the Panamint, Black, and Funeral Mountains, the overlying sediments having been eroded away. Once these Archean rocks were ordinary limestones, shales, sandstones, and granites; but they have been greatly changed by heat and pressure during their billion or more years of existence.

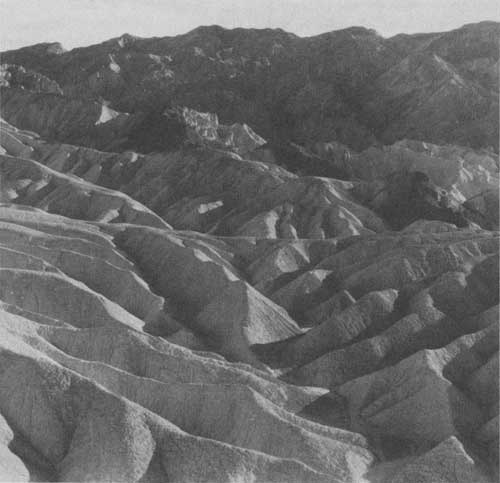

INTERESTING EXAMPLE OF EROSION

The succeeding group of rocks, those of the Proterozoic era, are also tremendously old, but much younger than the Archean rocks. They were laid down only after the Archean rocks had been worn away (eroded), a process which required a very long period of time. As compared with the Archean rocks they have been changed (metamorphosed) but little. They consist of limestone, slates and quartzites, and a dark volcanic rock now altered to greenstone. Some of the limestone beds contain fossils of primitive algae, representing one of the oldest known evidences of life. The rocks of this era are vividly colored in contrast to the somber tones of the underlying Archean rocks. They may be seen on either side of the valley near its southern end.

Next in turn comes the huge thickness of Paleozoic rocks, separated from those below by a profound break in the geologic record, called an unconformity. All of the great rock systems of this era are represented in the monument. They have been identified by means of the fossil remains of marine life that each contains. Thus for tens of millions of years this general region was beneath the sea, and thousands of feet of limestones and other marine sediments were built up. North of the central part of the valley the mountains on either side are made up largely of these rocks; and a fine section of these dark colored Paleozoic sediments may be seen along the northern side of Furnace Creek Wash.

The Mesozoic era, which succeeded the Paleozoic, is represented by granite which forced its way into the Paleozoic and older rocks; and by sediments and volcanic rocks whose exact age has yet to be determined. A large area of the granite is exposed in the mountains immediately north of Townes Pass.

The close of the Mesozoic era was accompanied by intense earth movements followed by long continued erosion, so that the next series of rocks (Tertiary system) were deposited on the beveled edges of the older rocks. None of the Tertiary rocks were formed in the sea. They include large amounts of volcanic rocks, indicating that the Tertiary was a period of long continued vulcanism in this region. Lava flows, ash and other kinds of volcanic rock, as well as water-laid sediments such as shale, limestone, sandstone and conglomerate, make up the great thicknesses of Tertiary rocks that account for most of Death Valley's unique coloring. Apparently there were earth movements at various times throughout the Tertiary period. Folding and faulting formed undrained basins that were occupied by intermittent lakes, and eventually filled by sediments. During early Tertiary time the climate was comparatively humid, but apparently has become progressively more arid, up to the present.

Fossil mammals found in the older Tertiary rocks, represented by the Titus Canyon formation (Oligocene), include a Titanotherium, a huge animal distantly related to the modern rhinoceros; and a small horse. Fossils of later Tertiary time are largely of a unique type, consisting of thousands of mammal and bird tracks found at several places in the monument. These await complete study, but represent the footprints of several kinds of horses, camels, antelope, carnivores, and wading birds that inhabited the Death Valley region millions of years ago. Strange enough, no bones of the animals that made the tracks have yet been found. Such tracks have been seldom discovered elsewhere, but apparently conditions for their preservation were ideal in this region. Other types of fossils, such as fish, shellfish, and plant remains are also known, and eventually a fairly complete idea of the life of the Tertiary period in Death Valley will be obtained.

The Tertiary rocks are best developed along the road from Furnace Creek to Dantes View, but are found at various places throughout the monument. Great deposits of borates and other non-metallics have made them commercially important in the past.

Pleistocene or ice age time is usually represented by glaciation. Here, however, there were no glaciers. Instead, a large lake occupied a large portion of the valley floor, and its shore lines or terraces can be seen at various places in the southern half of the valley. The "salts" at the salt flats and the Devils Golf Course were the last minerals to be deposited, as the lake dried up with the coming of the present extremely arid climate. The alluvial fans, particularly those of the west side, were also built largely during the latter part of the Pleistocene, and their growth has continued to the present.

Studies of the formation of the mountain ranges and the valley trough are far from complete. Their history is exceedingly complicated, and the earth movements that went into their building are seemingly different from those of other regions. However, it can be said that the valley owes its origin primarily to folding and fracturing of the earth's crust, and not, like the Grand Canyon, to erosion. It was probably blocked out in its present form in late Tertiary and early Pleistocene time. Death Valley is a classic example of the complex, tremendous geologic forces that have been at work in the past and that are, in part, still active in this region.

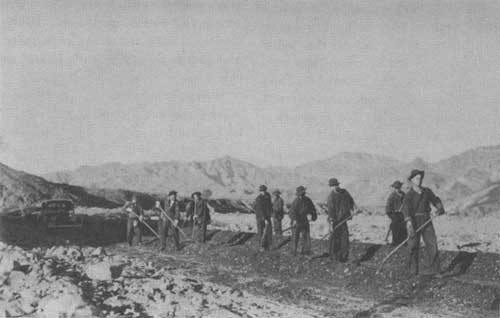

ROADS ARE EASILY BUILT AND SCARIFIED

HOW TO REACH DEATH VALLEY

BY AUTOMOBILE.—All but one of the main highways leading into Death Valley are oil surfaced, and all the other entrance routes are good desert-type roads. Within the monument there are over 200 miles of oil surfaced roads leading to the points of major interest. Other roads are being rapidly improved. Automobile travelers are advised to enter by one of the following routes:

By United States Highway No. 66 to Barstow, thence United States Highway No. 91 (Arrowhead Trail) to Baker; thence north on California State Highway No. 190 through Shoshone and Death Valley Junction into Death Valley at Furnace Creek. Driving time from Los Angeles to Death Valley by this route is from 7 to 8 hours. This route is oiled throughout.

An alternate route from Los Angeles is on United States Highway No. 6 through Mojave into the Owens Valley. Turn off at Olancha or Lone Pine on California State Route No. 190, cross the Panamint Valley and Townes Pass into the monument. Travelers from central or northern California can take either the Walker or Tehachapi Pass Roads from Bakersfield and join United States Highway No. 6 in the Mojave Desert, following the route given above from then on into the monument. An alternate entrance into the valley from United States Highway No. 6 is through Inyokern and Trona, thence over 35 miles of good desert-type road across the Panamint Valley and into the monument at Wildrose Canyon, where an oil surfaced road leads over Emigrant Pass to Death Valley.

From points north or east, via Reno or Las Vegas on Nevada State Route No. 5, turn off to Death Valley Junction, or at Beatty, Nev., and enter the Valley via the Amargosa Desert, the ghost town of Rhyolite, and over Daylight Pass into Death Valley. Both of these routes are oil surfaced.

Service stations are found at intervals along the route, but it is wise for the motorist to carry extra supplies of gasoline, oil, and water, particularly if leaving the main highways outlined above.

BY AIRPLANE.—An excellent gravel-surface airport with cross runways is maintained at Furnace Creek. Hangar space is available on the field and gasoline and oil may be secured there. Charter airplane service at most airports enables the air-minded visitor to enter Death Valley.

BY RAILROAD.—A combination rail and motor tour is available for Union Pacific passengers, leaving the train at Las Vegas and reaching Death Valley by car.

ADMINISTRATION

The officer of the National Park Service in charge of the monument is Superintendent T. R. Goodwin, Death Valley National Monument, Death Valley, Calif.

RANGERS

Park rangers are stationed at various points throughout the monument for the purpose of protecting the monument and the visitors. They patrol the roads, enforce the rules and regulations, and render all possible aid to the visitor. For accurate information ask a ranger.

NATURALIST SERVICE

Illustrated evening lectures on the history and natural phenomena of the monument are given at Furnace Creek Inn, Stovepipe Wells Hotel, and Furnace Creek Auto Camp. Inquire of a ranger or consult the Government bulletins at these places for schedules of naturalist activities and special events.

FREE PUBLIC CAMPGROUND

Located near the mouth of Furnace Creek in a side canyon surrounded by colorful hills, the Texas Spring Campground has been developed for use by those who bring their own camping equipment or travel with a trailer. Camping is free, but is limited to 30 days. Toilet facilities, running water, stone tables and benches, oiled and graveled roads, camp sites and parking spaces for automobiles and trailers, give accommodations for several hundred visitors. No firewood is available, and visitors should provide for an ample supply before entering the monument, or better still, carry a gasoline or oil camp stove. Firewood and other supplies can be purchased at Furnace Creek Auto Camp. Inquire of a ranger for further suggestions and camping information.

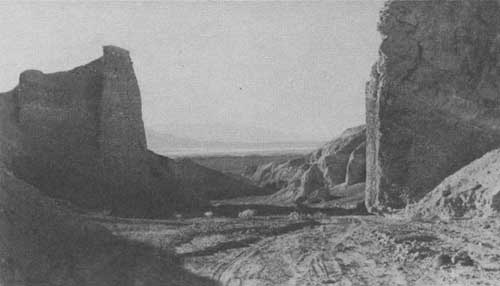

LOOKING NORTH FROM BREAKFAST CANYON

ACCOMMODATIONS

A variety of accommodations are available within the monument, and prices are scaled to suit the taste and purse of the visitor.

Wildrose Service Station, on the Trona-Death Valley Road, provides a store, meals and a limited number of cabins. All other hotels and auto camps are operated on private land, and the National Park Service exercises no control over them.

The Death Valley Hotel Co., with offices at 409 West Fifth Street, Los Angeles, operates Furnace Creek Inn and Furnace Creek Auto Camp. The Inn offers every luxury at a minimum charge of $9.50 per day for one and $15.50 for two, American plan. Rates are $2 per day and up, European plan, at Furnace Creek Auto Camp, with various types of cabins from which to choose. Trailer space is also available at a nominal charge.

Recreation facilities at Furnace Creek include a 9-hole golf course, swimming pool, saddle horses, livery service, and tennis and badminton courts. Filling stations, a store, restaurant, curio shops, and garage are conveniently located in this area.

Stovepipe Wells Hotel Co. operates a hotel and cabin camp in the vicinity of the sand dunes, 25 miles northwest of Furnace Creek. A restaurant, gas station and recreation facilities are available here. The minimum rate is $3 per day, European plan. Requests for reservations should be addressed to Death Valley, Calif.

During the summer months emergency accommodations may be had at places mentioned above, except Furnace Creek Inn, and also at hotels or camps outside the monument. During periods of heavy travel to the valley it is advisable to make reservations in advance.

|

A multilith folder containing a road map of the monument and a log of suggested scenic trips is available at the checking stations or at the monument headquarters. Supplementary mimeographed pamphlets on a number of the subjects treated in this bulletin are obtainable at the office of the park naturalist. |

RULES AND REGULATIONS

[Briefed]

The monument regulations are designed for the protection of the natural features and scenery as well as for the comfort and convenience of visitors. The following synopsis is for the general guidance of visitors who are requested to assist the administration by observing the rules. The monument belongs to the future generations as well as the present. Help us take care of it. Complete regulations may be seen at monument headquarters.

The disturbance, destruction, defacement, or injury of any ruins, relics, buildings, signs, or other property is prohibited.

Camps may be made at designated localities only, and must be kept clean. Place garbage and tin cans in receptacles provided for that purpose. Use gasoline or kerosene camp stoves or bring your own wood, as none is available. Do not throw refuse or trash on roads, trails, or elsewhere. Carry it until you can deposit it in a garbage can.

Do not pick, cut or otherwise destroy any flower, plant, shrub or cactus. Cutting of trees or shrubs for firewood, or any other purpose, is strictly prohibited. Hunting, killing, wounding, capturing, or attempting to capture any wild bird or animal in the monument is prohibited.

Use of firearms within the monument is strictly prohibited. Persons bringing firearms into the monument may be required to surrender them to any monument officer.

Gambling in any form is prohibited.

Private notices or advertisements shall not be posted or displayed in the monument except when authorized.

Vehicular and other traffic within the Death Valley National Monument will be governed by the current State of California Vehicle Code.

The penalty for violation of any of these regulations is a fine not exceeding $500, or 6 months imprisonment, or both.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/deva/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010